Rural Townships in the Western Cape

Map showing location of Zolani, Smitsville, Nkqubela, Zweletemba and Suurbraak in the Western Cape

Zolani (Ashton)

One of the things that struck me most whilst driving up to and around Montagu was the fact the each wine or fruit growing town had its own township. The spatial geography established by Apartheid is, perhaps not surprisingly, proving very resistant to change, at least on the face of things.

Take the township of Zolani (map), which is three kilometres outside of Ashton for example. (Ashton sits on the other side of the Langeberg mountains from Montagu.)

The township sits up on a bluff end underneath the Langeberg mountains. We drove by and could only see the first rows of dwellings but it was shocking to see - decrepit breeze block units, some with the windows knocked out.

A newspaper report paints a vivid picture of life in Zolani.

It’s also home to Elsie Sauls, a 52-year-old who lives in a part of Zolani township that has a rubbish dump on the hill above it and sewerage works below. When the garbage trucks come residents are covered with dust, and when the wrong wind blows the air smells foul.

Sauls’s household income consists of a R200 child support grant she receives for one of her three children, the scrapings she earns from irregular seasonal work on farms for three to four months of the year and a small income she derives from her sewing skills.

Like others in the township, Sauls is effectively trapped. If she wants to go to Ashton to buy vegetables the round trip will cost her R8 in taxi fares — an added expense to her shopping bill that she cannot afford.

If she wants to travel to Robertson, the next town, to take advantage of cheaper prices at the bigger shops there, it will cost R26, leaving her with no option but to buy whatever vegetables are available in the township at inflated prices.

Map showing location of Zolani Township in relation to Ashton, its factories and the sewerage works

A Community Access Roads Programme in Ashton funded by the National Poverty Alleviation Fund listed these figures for Zolani township in 2001:

- Number of Households 611

- Unemployed 843 persons

- Literacy age 14 and higher with grade 8 and higher 33

- Percentage of Households with income less than R1500 (£113.58)/month 77%

‘In the poorest part of Zolani Township in Ashton, Western Cape, South Africa, Pastor Fanie Tshoto started in a derelict building a church (the Apostolic Faith Mission Church). His intention was to give people a positive outlook in their lives. Of the approximate 6 500 people in this township 80% live below the poverty data line. There is only work in the fruit picking season when the lucky ones get a chance to work for 3 months in a local canning factory. For the rest of the year there is no work.’ Mamazolani

These townships were never an idyll of rural bliss or self-sufficiency. And they were protagonists in the struggle against apartheid.

For example, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission transcripts record vigilante violence in collusion with the police during township uprisings in Zolani in 1986. Sipho Joseph Sixishi was brutally assaulted by vigilantes and detained by the police for a month before charges were dropped. The assault led to the loss of an eye. Despite going to the Supreme Court he never received compensation.

The South African Press Association reported in 1996 a hearing of the TRC,

Municipal police joined forces with a group of vigilantes known as the Amasolomzi to conduct a reign of terror in the small Boland town of Ashton in the mid-1980s, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission heard on Tuesday.

The Amasolomzi, (Eye of the Community), were ostensibly recruited to combat crime in Zolani, a township neighbouring Ashton, with the support of the police and discredited community councillors.

The commission heard how they set up a dusk-to-dawn curfew and beat residents who broke it. In one of the worst incidents 24 residents were injured, eight seriously, when violence erupted between Amasolomzi and mourners attending the funeral of a "comrade" on May 24, 1986. Pringle Mrubata told how he lost the use of his legs after he was shot in the back by a member of the Amasolomzi when the vigilante group opened fire on a crowd gathered around a vehicle in the street.

See also the submission of Father Michael Weeder on general conditions in Ashton and Montagu under Apartheid in 1990 to the TRC.

Breede River Valley Townships including Nkqubela and Zweletemba

A major study of rural inequality and land reform carried out some interesting work in townships in the Montagu-Ashton–Robertson (the Breede River Valley administrative) area. It noted with regard to the Breede River valley area of the Cape Winelands that,

‘To a visitor it looks like a valley of plenty … [It] is extremely beautiful and very rich. However, it is also an area marked by poverty and inequality. … Substantial job losses on farms have prompted widespread evictions and the mushrooming of informal settlements ... where a large proportion of people are reliant on insecure, informal and seasonal employment ... and on social grants. The area … epitomises the contradictions of the commercial farming sector, which has been successful in providing paths to accumulation for some while entrenching poverty, underdevelopment and economic exclusion for others.’ (See Another Countryside at PLAAS, Chapter Seven p. 166.)

The household survey of townships in the Breede River Valley carried out by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies at the University of the Western Cape in 2008 included those at Ashton and Montagu. It revealed the following:

‘nearly three-quarters of respondents (72%) lived in formal housing – either a Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) house, an old council house or another formal house. Just 16% lived in a wooden or zinc shack.’

This varied between the townships and there was a category called ‘other’ that accounted for 12%. The survey report does not say what this ‘other’ is.

‘Most respondents (91%) live in homes connected to the electricity grid, and most (87%) had access to tap water at home, either inside or outside the house. This is a remarkable finding for residents of these poor areas: infrastructure for the delivery of basic services is fairly developed.’

The barrier here is not so much access as cost - ‘paying for basic services seems to account for a substantial portion of cash incomes in these communities.’

Just over half [56%] of the households reported receiving income from wage labour (regular or temporary), and the two next most frequently cited forms of income were from social grants. Nearly a third (32%) of respondents received some type of social grant [child support 29%, state pension 23% disability grant 9%].

However. most employment in the wine and fruit industries is seasonal. Work is particularly scarce when heating bills are at their highest in the winter.

More than a third of respondents lived in households where there had been no income from any type of employment.

A 'substantial portion' had no income other than social grants.

Remittances and work pensions were received by only 2% of households.

72% of the sample indicated that there had been times in the past year when they did not have enough to eat, usually in the winter months when there is little seasonal work on the farms or in the canning factories.

22% of respondents were involved in very small scale food production and there was a clear desire (75% of respondents) to have access to small plots of land (61% of respondents wanted access to a plot of an hectare or less) to increase this potential.

This is in line with much research on land reform in South Africa where most demand for land is for ‘smallholder production, primarily to supplement other sources of income, alongside a secure place to live, while the demand for larger plots for sizeable farming is restricted to far fewer people.’

(all above from Another Countryside pp. 170-176).

The report concludes that access to smallholder plots could make a huge difference to the rural poor who use multiple livelihood strategies that rely on a precarious combination of social grants, seasonal jobs on farms and informal work in towns to get from year to year (Another Country p. 181).

The report also notes that, 'the chasms left by the spatial divides of the old apartheid towns and commercial agricultural zones are almost entirely intact. The power that white commercial agriculture, white business and tourism hold in the rural economy also remains intact. We found no clear strategy from local, provincial or national government to regulate and transform the existing way the rural economy functions in this area' (p. 171 Emphasis added).

The Barrydale Gospel choir practicing for a concert in a shed

Added to this dismal picture is the devastating impact of the HIV/Aids epidemic in Southern Africa. The prevalence of HIV in the Western Cape in 2007 was estimated to be 16.2% across the region's population. In the Cape Winelands that prevalence increased from 11.4% in 2005 to 12.6% in 2007.

On top of this South Africa and the Western Cape in particular has a huge TB problem. Coinfection rates of Aids and TB in the Western Cape are estimated at 30% (see Boland/Overburg Health Status Report 2007/8).

See also pages my site at Wineland: Wine, Fruit, Labour and Land Reform

Smitsville

Or take the township at Barrydale, 63 km to the east of Montagu.

According to its website, Barrydale, is a thriving Little Karoo town of farmers and artists. It has a population of 2,444 (Black African 1.2%, Coloured 78.2%, White 20.6%). The township is called Smitsville but was also know as Steek Me Weg in Afrikaans -'Hide Me Away' (see The Overberg: Inland from the Tip of Africa, K Du Plessis and M. Cleary p. 162) and was created after the forced clearance of the Colured inhabitants of Barrydale.

The Oxford-based NGO Education for Democracy in South Africa ran a project at Barrydale called Net vir Pret (Just for fun) Its mission was

to encourage self-esteem, confidence and a sense of responsibility among the children of rural fruit pickers in the Barrydale/Smitsville area of the Overberg, Western Cape many of whom are depleted by alcohol and decades of degrading racism; thereby reducing the possibility of petty crime, dependence on drugs and alcohol, and lack of ambition among these children of the new South Africa.

Beautiful song and photos from Barrrydale

One of the project workers kept a blog on her visit,

Yet again the beauty of the surrounding mountains really struck me as I drove back to Montagu. Many of the children I saw were thin and undernourished - many had no food with them to eat at their break and lunch (there is however a government feeding scheme 3 times per week - however I have not yet seen this in action) they live impoverished lives in small homes often miles away from the school.

Amazingly there are a number of fabulous YouTube videos of the people of the township. These were all posted by someone who goes by the moniker of minooger (Anton de Villiers).

This is a nice Barrydale community site that is celebrating the booklaunch of the Just for Fun project.There is a new Net vir Pret website here.

Suurbraak

Suurbraak, on the other side of the Langeberg Mountains from Barrydale is a different kind of settlement.

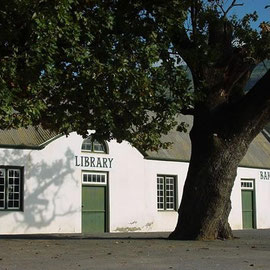

‘This traditional settlement drew the interests of the missionaries. It was established as a mission station in 1812 by the London Mission Society and later in 1875, taken over by the Algemeende Sending Kerk. In 1880 the Anglican church and school was built as a result of a split in the congregation. Community involvement in the church remains strong. The buildings of the village tell the story of its history. The first church, the parsonage and school, together with the old houses and buildings around the village square have been restored and are in use, as well as the Anglican church building. All are situated on the main road through the town.

The isolation of Suurbraak is one of its charms and limits the financial resources of the people. Many still cook on wood stoves, using an abundance of alien vegetation that grows in this area. The people live close to the land using farming methods that belong to the past. The smaller farms are still ploughed using horse-drawn ploughs. Agricultural work is often done manually. Many households own at least one cow and some horses. Horse and donkey drawn carts are often seen here on the streets.’

The first inhabitants of the area were the Attaqua [people] of the Quena people, and the town today lies on their ancient trade routes. The kraals (settlements) of these trading people possessed such natural beauty that they called it Xairu, meaning ‘beautiful’.

The community of Suurbraak has access to land, even if in small plots, because this was owned by the mission station. There is an acute housing shortage of

over 341 dwellings (see Swellendam Municipality 2011/12).

Photos of Suurbraak (courtesy of ViewOverburg.com)

Photos courtesy of ViewOverburg.com

Suurbraak Tug of War Team prepares for the World Championships