The Well of Loneliness: the existential impacts of the sea-surroundedness of New Zealand.

We spent three days on the Otago Peninsula in a bach on Papanui Inlet.

The Otago Peninsula manages to pack a lot of 'nature' into a small area. It has exposed headlands, wild Pacific beaches, wetlands, sheltered inlets, windblown sands, volcanic cones and steep sheep and bush country.

It captures one of the paradoxes of New Zealand. It is both benign and exposed; homely and harsh and easy but ill-at-ease.

The Settler's Terror of Loneliness

I came across these haunting sentences in the recollections of an early Scottish settler at Inch Clutha (below Balclutha in Southern Otago) on the rich alluvial flats of the Clutha/Mata-Au river.

Our delight in human society, I consider purely the natural effect produced by a corresponding depressing loneliness and isolation that the settlers had to continually fight against, knowing instinctively that, if it got him down, he was done for.

Solitude has its charms and its own place and time, but it also has its terror. An experience that must be felt in its true sense to understand it. I once felt that really solemn feeling pointing clearly towards terror. It was on top of Ben Lomond, above Queenstown, as I looked from that solitary peak, miles away from any living thing. The absolute loneliness of the situation came home to me as something absolutely appalling, akin to terror, just the sense of being so far from any living thing. I was thankful I was not alone, as there were three of us. That is something of the feeling that gets into the lonely settler’s very blood and the joy of company was pure delight.

(Source: Pioneering in New Zealand 1859 - 1863: a record of

Agnes Archibald, wife of James Archibald)

I don't know if this almost primeval 'terror' (as he calls it) of loneliness and isolation still resonates for New Zealander's, but I felt I was, as the container-inhabiting women of Top of the Lake might have said, 'picking something up'.

For thoughts on the Jane Campion directed 'Top of the Lake' TV series set in Glenorchy to the north of Queenstown see my Leaving Otago.

Sometimes New Zealand can feel the most lonely place in the world and the huge distance from home and the familiar rushes into the void.

No wonder the All Blacks are so good at rugby. You'd want something to dedicate yourself to to keep that lonesome feeling at bay.

Lady Barker (Mary Anne Barker nee Stewart) wrote about this aspect of 'lonely New Zealand' back in the 1866 on the Malvern Hills sheep run she and her husband were soon to sell to return to the UK after the disastrous winter snowstorms of 1867 killed half their sheep flock and 90% of their lambs (p.72),

But after the house is quiet and silent for the night, and the servants have gone to bed, a horrible lonely eerie feeling comes over me; the solitude is so dreary, and the silence so intense, only broken occassionally by the wild, melancholy cry of the weka. (Station Life in New Zealand, 1870 p.34.)

You can experience the melancholy cry of the Buff Weka here.

I wasn't sure if the sense of exposure I felt on the Otago Peninsula was greater than in West Cornwall where I'd lived for 10 years. Exposure is after all part of the definition of being by the sea.

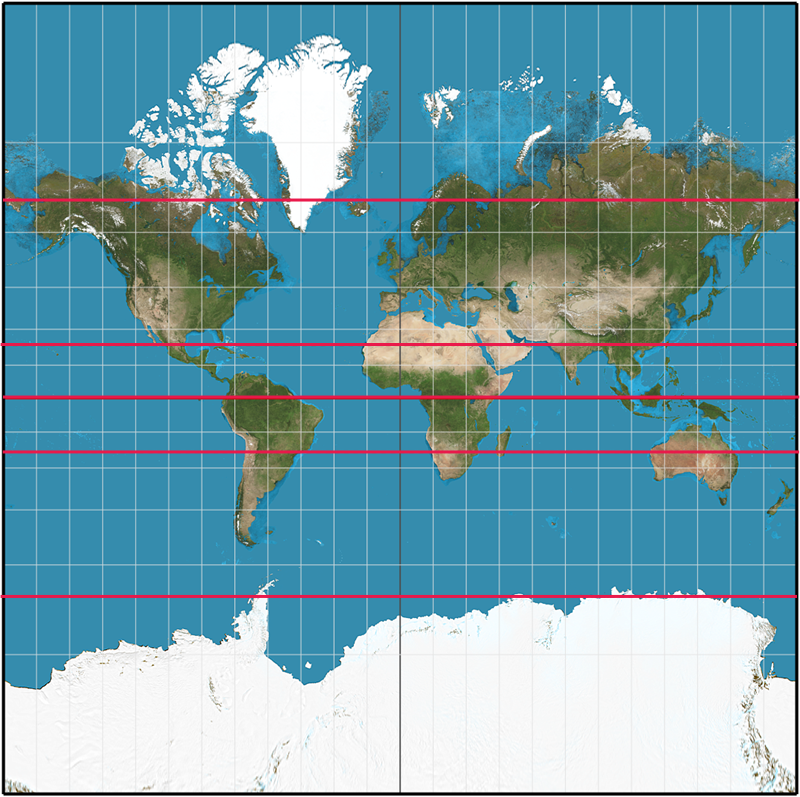

So I thought a bit more about it. And did some latitudinal comparisons of New Zealand and the UK's comparative positions from the Poles and the Equator.

The Latitudinal positions of New Zealand and the UK compared

Bluff (pop. 1,850) at the southern end of the South Island lies at latitude 46.6°S.

Lerwick (pop. 7,500) in the Shetland Islands at the northern end the UK lies at 60.15°N.

So Lerwick is much closer to its pole than Bluff is to the South Pole.

But if we look at Bluff's position by something I here call 'transposed latitudinal equivalence' the city closest to it in Europe is Bern in Switzerland (46.6°N) (see the very useful List of Cities by Latitude).

In fact, the Lizard Point, the UK's most southerly headland at latitude 49.9°N is further from the Equator than Bluff (which for argument's sake is like the UK's Lerwick) by something like 200 miles.

Confused? Well I was. But what I'm saying is simple really: all of the UK is 200 miles further from the equator than even New Zealand's most southern mainland point.

Did that help? Here's another way of thinking about it. The north-south length of New Zealand from the South West Cape on Stewart Island (off the southern end of the South Island) and the North Cape at the end of the North Island is about 1513km/940 miles.

If you were to cut out a map of New Zealand, turn it upside down and place Bluff at Bern in Switzerland (transpose latitudinal equivalents) on a map of Western Europe the tip of the inverted New Zealand's North Island would - on a strictly north-south basis - nearly reach Tripoli in Libya.

(The closest city as a latitudinal equivalent to the North Cape at 34.4°S is Sfax in Tunisia.)

Which little exercise goes to show that all of New Zealand - even that bit that seems so far south in the Pacific Ocean - is closer to the Equator than the UK.

You could also imagine this by putting a map of the UK upside down in the Pacific. The Lizard Point would be approximately 200 miles south of Bluff en pleine mer and Lerwick would be a further 660 miles south in an even pleiner mer - the Southern Ocean.

Some joker in New Zealand said to me that you can't do this kind of latitudinal comparison due to the fact that the Earth is tipped off its vertical axis by an angle of 23°.

As if this somehow might disadvantage New Zealand by 'tipping it down in the Universe'. But it's all compensated for by the Earth's orbit round the Sun. In the UK winter, even plucky 'little' New Zealand (which is actually 10% bigger by surface area than the UK) is closer to and more directly in line with the sun than bully-boy Britain.

You might have to wear swimming trunks at Christmas. But that's not so bad, eh?

By which time I'd drifted a long way from my initial thoughts about the sense of exposure on the Otago Peninsula.

But the thing that makes a difference and stops Bluff being like Bern and stops the North Cape being like Sfax in Tunisia was staring me in the face. It is of course that colossus, that repository of 50.1% of the world's salt water. It is the Pacific Ocean, (with walk-on parts by Tasman Sea and her big, cold brother, the Southern Ocean).

Returning to my comparison of Otago and Cornwall I had a look at some weather data.

Average wind speeds for Dunedin Airport and Plymouth, UK look roughly equivalent. The major difference being that Dunedin gets more south-westerlies (which in the Southern hemisphere are cool sub-Antarctic winds) than Plymough gets of the transposed equivalent north-easterlies.

Temperatures, sunshine hours and rainfall vary: Cornwall is wetter and gets 200 hours less of average sunshine. Cornwall's summer average temperatures look slightly higher but there is not a lot in it. Winter averages and average sea temperatures are broadly similar (see Met UK and Otago Regional Council and seatemperature.org).

|

The climates of Coastal Otago and Cornwall Compared

|

||

| Climate | Coastal Otago | Coastal Cornwall |

| Latitude | 45.2S | 50.3N |

| Winter average | 4-10C | 4-9C |

| Summer Average | 11-18C | 16-19C |

| Rainfall | 660mm | 950mm |

| Sunshine hours | 1800 |

1600 |

| Prevailing winds | SW (most) and NE |

SW and E and ENE |

| Av Sea Temp | 11.1C |

11-12C |

So the exposure to wind rain and sun in Cornwall and Coastal Otago are really not that different.

Maybe New Zealand feels more exposed because I felt more exposed and a long way from home.

Or maybe that sense of exposure is more to due to the absolute predominance of the great oceans in the southern hemisphere over the land and the brooding, if distant, presence of the massive continent of Antarctica.

(Antarctica has a surface area of 13.2 million km² or 5.1 million miles² which is 1.7 times the surface area of Australia).

The predominance of water over land is particularly heightened in latitudes beyond 35 degrees South (which is just beyond the tip of South Africa).

Only four countries have significant landmass beyond this degree of latitude in the Southern Hemisphere - Argentina, Chile, South Eastern Australia and New Zealand - (and Antarctica but it only starts beyond 60 degrees South) whereas most of Europe, North America, Russia and Asia lies beyond 35 degrees N in the Northern Hemisphere.

So maybe exposure is the wrong word and isolation, distance from others, and surroundedness by sea, is the right way to think about it.

Traveling due east from Bluff at the end of the South Island the nearest country is Chile (Bluff to Santiago is 5,797 miles) and traveling west the nearest country is Argentina (6,116 miles to Buenos Aires). The distance to the nearest significant landmass from Bluff is 1,059 miles (Tasmania).

The winds may not actually be stronger in New Zealand than the UK but there is a sense they should be, particularly in the South Island, because there is nothing to the east or west for nearly six thousand miles but wind and water.

And, of course, the waves are bigger and the power of the sea greater because the maximum due westward fetch for the wind is bigger - in fact it is way over twice as big (the distance from Lands End to Newfoundland is 2,236 miles compared to Bluff to Buenos Aires at 6,116 miles.

Add to this isolation from other land masses, the very low density of human habitation in New Zealand, (10% bigger in surface area than the UK with only 4.4m people compared to the UK's 60 million) particularly in the southern and western halves of the South Island and that exhilarating and existentially-threatening sense of exposure begins to make some sense.

There's a nice little reflection on that existential difference in Eleanor Catton's (2013) Mann Booker winning novel, The Luminaries. The recently arrived, and aptly named, Moody recollects his first impressions in the summary chapter of Part I of the book,

'Disembarking the packet steamer [at Dunedin]... he had cast his gaze skyward, and had felt for the first time the strangeness of where he was. The skies were inverted, the patterns unfamiliar, the Pole Star beneath his feet, quite swallowed ... He found Orion - upended, his quiver beneath him, his sword hanging upward from his belt ... There was something very sad about it. It was as if the ancient patterns had no meaning here ... It had bothered him extremely that there was no star to mark the pole.' (p.342-3)

I went through this exact same sequence looking at the night sky at Pohara in Golden Bay (at the north west end of the South Island).

There was Orion but he seemed upside down and search though we did we could find no southern Pole star nor even the Southern Cross. Moody reckons there is some kind of formula for finding it, ' the length of a knuckle, an equation.'

This is the formula that Moody didn't know.

'A technique used in the field [to identify the Southern Cross] is to clench one's right fist and to view the cross, aligning the first knuckle with the [long] axis of the cross [pointing towards its longer end]. The tip of the thumb will indicate [celestial south pole]' ( see Crux).

Reading through this page some time after 'finishing' it I wondered how that sense of isolation and distance played into New Zealand's 'national psyche '. I'm sure there are books written about this and we don't really talk about national 'psyches' and 'characteristics' anymore because they were so often expressions of hegemonic views and particularistic claims to national belonging.

But I came across a piece of advertising-led research on a Mexican-Kiwi's website that suggested seven key Kiwi characteristics. The video below is of the advert that was made from the research.

This research suggests that Kiwis:

- put high importance on their bond to their land

- put a high value on their freedom

- have a masculinity of expression: stoicism and blokeyness

- see sport as their therapist, their way to international recognition through graft and teamwork in which the individual (the famous 'tall poppy') is subsumed in collective effort and judged by a universal yardstick

- derive great succour from mateship as the essence of Kiwihood, with a strong sense of egalitarianism even if not always so in practice

- see themselves as easy going, and yet they are conformist and resistant to change while being laid back about it all

- revel in their understated and laconic sense of humour.

I think the add below was supposed to capture this.

For a 1966 view of National Characteristics see the old Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. On page nine on the 'Effects of Insularity' the author, A.H.McClintock wrote,

At the same time the experience of living in a land apart has imbued them with an insular pride that prompts them to maintain a somewhat exaggerated estimate of the excellence of their own institutions. Though anxious to learn and fully aware that nothing is to be gained by pursuing self-sufficiency, they are oversensitive to outside criticism, even though it be constructive. Visitors who comment unfavourably risk execration by the local press.

'The Effects of Insularity', from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H.

McLintock, originally published in 1966.

For some interesting, if provocative reflections on the continued influence of the UK on cultural continuities in New Zealand see Kuiper (2007) from the University of Canterbury. Christchurch. He puts forward the following view:

I have suggested that when one looks at the vernacular culture and folklore of New Zealand and realises that much of it came from Britain and is still British in its character then it must also be manifest that the cultural apron strings that bind Pakeha New Zealanders to the British Isles are stronger than any other strings, even than their own creative twistings.

Kuiper, K. (2007)New Zealand's Pakeha Folklore and Myths of Origin Journal of Folklore Research, Vol. 44, No. 2/3