The Milford Pages II: Bluff to Te Anau

This was a frustrating half day's drive. But brilliant too.

We left Bluff at 9.20am after our early morning Foveaux Strait crossing from Stewart Island. We had a 5 hour and 13 minutes drive (according to the NZ AA) ahead of us to Milford Sound. We needed to be in Milford in time to board our boat at 4.00pm and have some time to stop, to take pictures and enjoy the drive into Milford Sound.

That meant keeping the car rolling along nicely on the first leg of the journey, particularly as we were unsure how long our real-time journey would be.

On the Bluff to Te Anau leg then it was really a question of snatching photos as and where I could, often from the car or just beside it.

In the end we had more time than we thought but the idea of getting to Milford and missing our boat, a three course meal and our berth for the night put a special spring into that day's acceleration and braking.

There's a section on the controversial Manapouri hydro scheme at the end of this page that links it back to Bluff and Tiwai Point aluminium smelter.

It would have beeen interesting to stop in Invercargill/Waihōpai (pop. 52,900). I don't know why but for me there has always been something familiar about the name 'Invercargill'.

I'd lost my lens cap on Ulva Island and had an eye out for a camera shop. Our route took us along the main drag - a 40m-wide street with low-rise shops fronting on to it - in a northerly direction. It felt like a town out of a Western made to accommodate thousands of cowboy-driven cattle.

In fact, the airport was used as a final fuelling point for the USAF planes heading for the Antarctic in Operation Deepfreeze in the 1950s. Take off on the short runway was assisted by JATO - Jet-Assisted Take Off - and the first plane to touch down at the South Pole was the optimistically named U.S. Navy R4D-5L "Que Sera Sera'.

On a mission like that you'd have thought they might have used a plane with a name like 'Fortitude' or 'Certain Glory' 'but 'Che sera sera'? Perhaps they were using Jest-assisted take off?

Invercargill, under the influence of its Scottish Free Church associations, voted for the prohibition of alcohol in 1905 - a dry edict that was only overturned with the return of thirsty and belligerent IIWW soldiers in 1945.

Not that the beer and spirits stopped flowing but the form of circulation changed - huge keg parties in peoples' homes, beer sold by 'keggers' hidden around the town and shops selling booze in outlying districts.

However, a monopoly on alcohol sales was vested in the Invercargill Licensing Trust which returned monies to local civic amenities projects. And alcohol is still not sold in supermarkets.

Anyway, we didn't see a camera shop and we didn't need booze. The big broad street gradually petered out into that neverland of car showrooms, garden centres and municipal works depots. We pushed on across the broad plains that have brought dairy gold to Southland in the great milk boom.

We drove west and hit the south coast again at Riverton/Aparima (pop. 1,431) where we briefly stopped, presumably for a coffee but I have no recollection of it.

The tide was out in the Jacob's River Estuary and the little town felt very much at ease with itself. As Southland's oldest permanent settlement, Riverton has some lovely examples of vernacular domestic and church architecture but I missed them and took photos of functional bungalows and the splendid Christadelphian Bible Hall. Clearly another visit to the town is merited given the fulsome entry in Wikipedia.

Western Southland is clearly pissed off at missing out on the tourist boom. There is an interesting if somewhat unresolved commmunity-based promotional website here with podcasts on topics such as 'kit-set homes in early Riverton'; 'the Tuatapere Timber Mills'; and the 'Helen McKay Pikelet Recipe'.

We pressed on along the estuary to Colac Bay/Oraka, a big surf spot with spray from the Southern Ocean swell misting the air. I pulled into a field entrance and took a few photos of the sun on the nitrogene-green grass, the spray and mountains behind. In the distance a bizarre bungalow with a silvery roof and pointy turrets caught my eye.

The Rough Guide had made our route sound interesting. It talked about 'the fringe country where the fertile sheep paddocks of Southland butt up against the remote country of the Fiordland National Park' (see Rough Guide, 2012, p.778).

Perhaps we were going too fast and needed to head up some gravel roads pointing westwards but I never quite felt we did enough 'butting up' to the 'remoteness' on this road, pleasant and fast though it was despite the warnings about sheep being the major traffic hazard. (They weren't).

Near Clifden I snapped a photo of some sheep and a tin shed with green-blue mountain ranges marching by in the distance.

I love all the tin sheds in New Zealand. Corrugated iron must have been a Godsend in high rainfall areas and devastating earthquakes soon taught New Zealanders to use light and flexible construction materials.

An outcrop of limestone occurs at Clifden and there are some caves. I took a photo of an interesting limestone rock face, etched away by carbonic acid. Clifden also boasts what was once the longest suspension bridge in New Zealand. But we didn't see it and you can no longer cross it, even on foot. Which is a shame.

Then we were on our way again through Round Hill, Orepuki and Waihoaka before the Southern Scenic Route turned north away from the sea and up the valley of the Waiau River to Tuatapere.

Again it would have been fantastic to stop and follow the road west from Clifden up to Lake Hauroko and the beginning of the vast unsettled Fiordland National Park. But time pressed. We went through Otahu Flat and up Bell Mount road with a vista that began to open out on the Hunter Mountains.

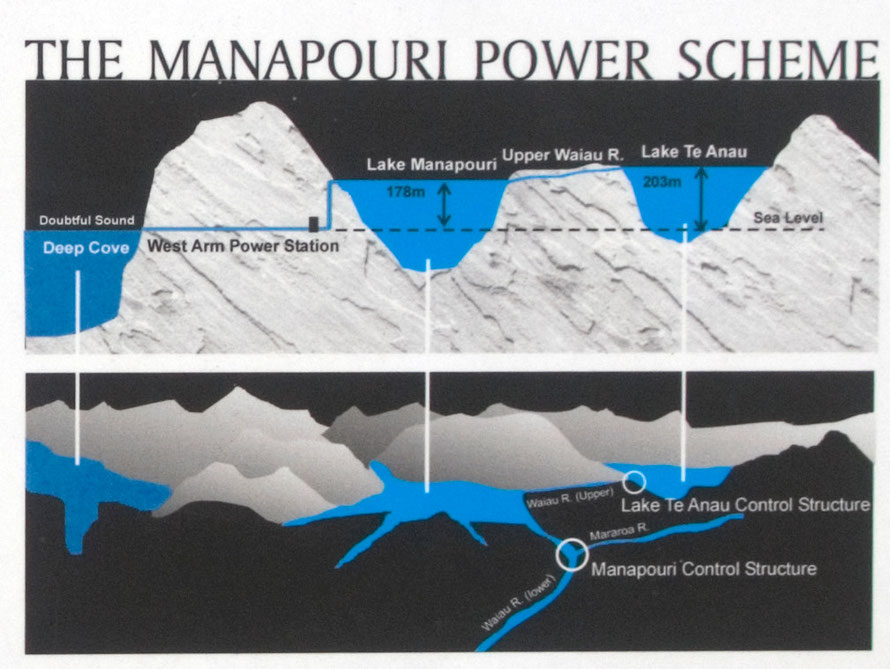

Pylons came marching across the hill and I guessed these were from the huge Manapouri hydro scheme to the north that was built to feed the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter's insatiable appetite for electricity. (They were and they were taking 15% of New Zealand's generated electricity to smelt alumina at the smelter in Bluff).

The Waiau River Valley

The road dropped back down to the valley flats and then skirted north-east around Black Mount (539m) to rise up over a col and drop down the side of the Red Cliff Creek back into the Waiau River valley.

The pastures in the valley bottoms were baked to a toasty golden hue and the strips of planted pines stood out stark against them. The mountain peaks were starting to get higher and we travelled further north with a growing sense of excitement. The traffic on the road was sparse indeed.

We were already in the rain shadow of the mountains to the west.

On the valley flats the road went arrow straight and what traffic there was seemed to have a complete disregard to New Zealand's speed limit of 100 kilometres per hour. We learnt from the locals and picked up the pace.

The golden paddocks of late summer dried grasses were enchanting. They had that dried-out, intricately detailed look of an Andrew Wyeth egg-tempera (egg-yolk based) painting.

I could almost see the stretched-out figure of Christina, shuffling her way through the grass, from the painting called Christina's World (1948) of his neighbour crippled by polio in coastal Maine in the USA.

Here the mountains were trying to 'butt up' but they were still too distant and separated from the paddocks by the wide Waiau river valley.

I'd stop and take photos, frustrated with the impossible contrast between the bright sky, dusty mountains, dark green-to-black conifer shelter belts and the glowing blonde-yellow-reddy grasses.

I'd curse and stretch further into the prickly wayside to try and exclude an obtrusive fence from the viewfinder. And laugh and joke with The Principal and apologise again and leap back into our little Toyota and barrel it until the scenery changed enough to force another stop.

It was exhausting and exhilarating. The sun shone, a gentle breeze made the dried grasses sigh and susurrate and the open empty road stretched out ahead of us.

We rose up and fell back to earth again and went through stretches of country that seemed to have been made in the image of England - poplars and willows with open paddocks in front reminded me bizarrely of the black poplars on Port Meadow on the Thames flood plain in Oxford.

Except here everything was cast in a golden light. The overpowering Leaf and Hookers greens of an English summer had here been burned away and back to something more elemental and joyous. And the country was so empty, just so bloody empty.

We inspected a few self-congratulatory signs at the confluence of the Waiau/Mararoa river with guffawing scepticism (with ample justification as it turned out). But the scene was enchanting.

(I've covered some of the river dams controversy in my page on New Zealand's biggest river, the Clutha/Mata-Au. There is more to come on this page on the Manapouri scheme.)

Yellow-green pasture backed onto blonde paddock that was punctuated by bubbling copses of rounded, autumnal-yellow willows (or I at least assumed they were willows).

These were backed by ranks of dark green trees and sun-studded hillocks behind them. Low clouds, that must have marked the presence of unseen Lake Manapouri, straggled along at the foot of a range of dusky, muscular mountains with a jagged profile that growled quietly against the broad bands of high cloud working from south-west to north-east across the sky.

There was an intimacy and harmony to the colours and shapes, to the flow of field and forest, sky and hills that is often missing in New Zealand. Sometimes it all just feels a bit too bloody functional.

As if someone had said,

'Right mates, we'll rip out the old biota and wedge in our sheep and exotic grasses from Europe. Then we'll get wealthy on small-scale lamb and dairy farming with the advent of refrigeration.

We'll live the good life but just to buck ourselves up we'll down a sick-bucket of Rogernomics and get rid of all agricultural subsidies and expose ourselves to the full force of Chinese-led globalization.

And then we'll start producing dried milk powder in such earth-shattering quantities through the use of airspread nitrates and superphosphates that we won't know what to do' (for more in this

vein see my pages on New Zealand's agricultural butter fat

arcadia).

But here it felt different. Well at least for a while until we went by a big black Angus bull in a field and a sign that told us the beast was a 'Landcorp sire'.

Then it felt like we were back in the driven world of cut-throat agriculture although in fact Landcorp is not some 'evil private sector agribusiness' but a state-controlled agribusiness.

Anyway. the day was too good to be spoiled by a few signs and a sickly pastel-lime green office with two pointed yellow cedars growing either side of it.

We were still exultant with our good luck with the Foveaux Strait passage and the time we were making through the sunny Western Southland fringe country.

The road arced across the valley floor, marked out by white lines and little reflecting posts. The country round us was vast but ordered and welcoming. It had a broad, straight spine and strength like the bull we had seen. The mountains contained the valley in a warm, airy grip.

Here in the rain shadow of the granite heights of Fiordland the overpowering wetness of much of the South Island was held in abeyance. You could have cut yourself on the clarity of the air and swooned in its fullness without falling over.

Not that we did any swooning because time was pressing, always pressing and by some ill-imagined quay a boat was waiting. (It wasn't at the quay at all as it carried tourists around Milford Sound on the day-shift.)

We had our little residual anxieties about leaving our car and our gear in some wayward isolated spot exposed to any crim who could be assed to drive the 226km round trip from Te Anau to rip off waterproofs and an unread copy of Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch.

On Donna Tartt the book remained unopened the whole month we were in New Zealand. Sometimes a book has to be carried around before it becomes readable.

Months later I'm devouring it in huge chunks, hardly daring to turn out the light as the night slips by midnight and the sound of the never-ceasing Dover/Calais ferries drifts through the open window.

We drove on and I marvelled at the nearer hills stripped bare. Multiple scars like a lash's welts were eaten into the steep slopes. Rocky defiles crowned the pinking-shear ridges.

Where had the bush gone? How had it been cleared so high up? Had the sheep simply eaten it out and left the hills naked to gravity and the Southern Ocean troughs that even here could dump water on the heights like a tipped-up Olympic pool of torrential rain?

And then we were on the slope above the shores of Lake Manapouri and looking at the spectacular Cathedral Peaks over the flat calm water. Suddenly were back in that dense green mountain and forest thing.

Lake Manapouri was strangely underwhelming. The light had flattened out and the dark, forested mountains and tops of the Cathedral Peaks looked glum.

It was noon with the sun is at its highest. The dark hills seemed to drink in the available light. The camera simply could not comprehend the contrasts of intense shade and bright sky. The Nikon algorithms couldn't cope.

Lake Te Anau

We pushed on feeling abashed at not being more impressed and soon rolled into the lake front bungalow land of Te Anau.

I bought a few provisions in the very modern, tourist town (4,000 tourist beds) and we pottered along the Te Anau lake front past the marina and Blue Gum Point. We ate a quick sandwich and petrolled up. The guy in the filling station said it was not much more than an hour and twenty to Milford. We set out, glad to be out of the town.

Despite the difficulties with the light Lake Te Anau is pretty impressive. It's 65km long and has a surface area of 352 sq km and reaches a maximum depth of 417m. It has three fiords that branch westwards off the main south-north body of water and is the biggest lake by volume in Australasia.

Several rivers feed into the lake, the most important of which is the Eglington, the longer west branch of which has its headwaters in Lake Fergus !

The Lake Te Anau catchment is 3,100 square kilometres and Lake Manapouri's is 1,390 km2.

The major rivers flowing into Te Anau are the Clinton, Doon, Glaisnock, Wapiti, Upukerora, and Worsley. The 'burns' include the Billy, Snag, Ettrick, Mid, Loch, Junction, Point, Woodrow, Mystery, Chester, McKenzie, Delta, Tutu and Gorge.

Te Anau flows out into the Waiau River which then flows into Lake Manapouri before flowing due south to flow into the sea at Te Waewae Bay.

The Waiau catchment has been developed for hydro-electric power generation, with the Manapouri Hydro-Electric Power Scheme operating on the western arm of Lake Manapouri. This has resulted in the diversion of up to 90% of the flow in the catchment.

Not surprisingly, 'the Waiau and Mararoa Rivers are often subject to extensive algal growths and at times blooms of the invasive Didymo' (Land Air and Water

NZ).

('Didymosphenia geminata, commonly known as didymo or most unpleasantly as 'rock snot' is a species of diatom that produces nuisance growths in freshwater rivers and

streams says Wikipedia.)

The Mararoa weir together with reduced water flows in the lower Waiau River acts as a barrier to migratory indigenous fish passage (long finned eels, lampreys, koaro and torrent fish)' (Fiordland National Park Management Plan 2007 p.50).

This is not surprising as the Manapouri hydro scheme has cut off their headwaters to flush them out miles to the west straight into the sea at Doubtful Sound.

The Mararoa river is controlled by dams below the lake and the river is pushed up the Waiau riverbed into Lake Manapouri to feed the hydro scheme.

Water flow was reduced in the Waiau from 400 cumecs to 1 cumecs. It has been 'won back' to a flow of 12-16 cumecs and a little more in the summer 'for jet-boat access up to the weir'. That does not figure as a glorious 'winning back' in my opinion.

Manapouri Power Station is an underground hydroelectric power station and is the largest hydroelectric power station and the second largest power station in New Zealand.

Completed in 1971, Manapouri was largely built to supply electricity to the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter near Bluff, as well as into the South Island transmission network.

The station utilises a 230 metre (750 ft) drop between the western arm of Lake Manapouri and the Deep Cove branch of the Doubtful Sound 10km/6.2 miles away. In effect 90% of the water that used to run down the Waiau River now runs into the sea at Doubtful Sound.

16 workers were killed in the construction of the station (Wikipedia: Manapouri Power Station).

The Manapouri scheme was controversial from the start and designed to smelt bauxite from huge deposits found in Australia in the 1950s.

Demand for more electricity in the 1970s led to plans being drawn up to dam Manapouri Lake such that it and Te Anau became one massive lake 30m higher than the current shoreline. Huge protests in the 1970s, with one in ten of the adult population of New Zealand signing a petition against the scheme, halted it in its tracks. However, the Clutha/Mata-Au river hydro scheme at Clyde was perhaps a compensation for the set back at Manapouri (see my Clutha/Mata-Au page).

The Tiwai Point aluminium smelter produced 354,030 saleable tonnes of aluminium in 2011 and employed approximately 750 full-time workers and 120 contractors in 2009.

The plant is owned by Rio Tinto Aluminium (79.4%) and Sumitomo Chemical Company (the rest). The plant uses about 15% of all the electricity generated in New Zealand (see Wikipedia: Tiwai Point).

At the one house party I went to in Auckland I got chatting to a bloke who had been one of the engineers at an aluminium casting plant in New Zealand that used feedstock from the Tiwai Point smelter. At one time they were making all the wheel castings for one of Ford's most popular models.

This was based at the Ford New Zealand Alloy Wheel manufacturing plant in Wiri, Auckland. The Wiri plant was the only aluminium alloy wheel plant owned by Ford in the world.

In the early 2000s the plant was sold to ION Automotive NZ Ltd (IANZ), a subsidiary of an Australian investment company, ION Ltd. The New Zealand ION operation was closed in 2006 with the loss of 500 jobs following the placement of ION Ltd Australia into voluntary administration. At the height of production the Wiri plant was producing 1.7m wheels a year (see National Business Reveiw).

The future of the Tiwai Point smelter has been in the balance of late as Rio Tinto has battled to reduce the price it pays for energy as global aluminium prices have fallen. (For photos of the Tiwai Point smelter see my Bluff page)

So a day that started in Stewart Island came to half time in Te Anau. The Milford Road beckoned.

Later on our return to the UK I found out more about the Manapouri scheme. It felt like some kind of betrayal to have been travelling through the Waiau valley when its flow had been so compromised upstream.

The thought of allowing a trickle compared to the old flow to allow jet boating on the Waiau seems like sacrilege to me and is testimony to the power of the tourist dollar and lobby in New Zealand, I guess.

You can't make new countries without breaking eggs (and New Zealand is so new it still has the mould-sheen on its fresh-minted backside) and no-one in Europe has much of a moral high ground on which to stand in these matters. Still, its a shame to think that the the long finned eel, the lamprey, koaro and torrent fish will not be making their way up the Waiau any more.