War

Under construction

I wondered how far I could get with a page about New Zealand and War. You can't help be struck wandering around New Zealand how many War Memorials there are. These are by and large to the First

World War in particular, The Second World War and other British Empire campaigns - the South African War (?).

But there is a longer history of the war within New Zealand between the European settlers - later to be known as 'pakeha' - and the Maori population - organised into its nations/tribes of 'iwi'.

And there were also wars between Maori iwi before the Europeans arrived and during the successive waves of European immigration and settlement.

Clearly the 'wars' were of different scale and location and the technologies and pursuit of aims varied hugely but they all to a greater and lesser extent and with greater and lesser intensity and ferocity involved, armed and organised conflict and violence.

These web pages are only really notes (and often pretty scant at that) towards a better understanding of New Zealand at a pretty personal level - some of the themes I am interested cover things like New Zealand's exoticism, geographical isolation and its connection and separation from the UK and Europe.

These pages are also a way of exploring New Zealand as a prism for looking at broader themes - for example the Decline and Fall of the British Empire or 'British imperialism' as we used to call

it (say in comparison with experiences in South Africa and Cyprus), the butting up of economic development against environmental limits and particularities and the that whole strange thing of

imagining oneself as a settler and adventurer in a country that offered such rich possibilities for both.

Here I can't hope or aspire to say anything much original about New Zealand's 'wars' and my focus is more on the way they are publicly remembered and visible to the wandering eye of the tourist than their actuality. But it strikes me that New Zealand consciously or not presents a picture of itself as a pretty benign place separate from the horrors of the 19th and 20th centuries.

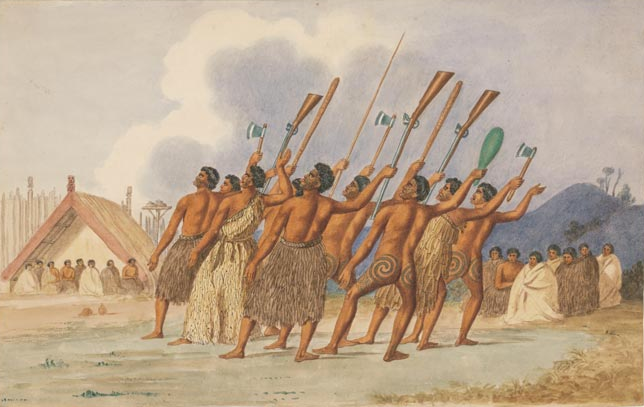

It projects a reputation for toughness and small-country obduracy and independence epitomised in the All Blacks rugby team and its mythical origin in the family farms of New Zealand. But wars and warfare - other than the tragedy summed up by the word 'Gallipoli'- are strangely absent save for the residualised theatre that is the Maori 'haka' the precedes All Blacks' international rugby matches.

New Zealand was gearing up for the centenary commemoration of Gallipoli - (Cannakale' in Turkish) on ANZAC Day (25 April 2015) during our stay. See Robert Fisk here on the cynical choice of 24 April 2015 by the

Turkish government 'in an unprecedented act of diplomatic folly' to bury the genocide of one and a half million Christian Armenians carried out by Ottoman Turkey. ANZAC Day is celebrated in

Australia and New Zealand on April 25th.

So Gallipoli seems a good place to start. Not only because the centenary was approaching in 2015 on 25th April, Anzac Day, when the disembarkation at Gallipoli began. But also because as I walked

across the patchy greensward of the Auckland Domain towards the hilltop Museum and War Memorial I ran into a film crew making a fiml or TV programme about Gallipoli (althoough as yet I have been

unable to trace it).

Austrailia's Channel Nine TV made a seven part mini series to commemorate Gallipoli.

The Thirst for Empire Glory

At the outbreak of the IWW New Zealand was keen to be fully involved, having first been 'blooded' in the South African War (1899-1902).

At the turn of the 19th century New Zealand had been a British colony 'for a mere six decades' and despite its many achievements,

'the one thing the country had not done, and was thirsting to do, was send troops abroad to represent it [the British Empire] in combat' (King 284).

The South African War (1899-1902)

The outbreak of the South African War in 1899 afforded New Zealand its first opportunity to send abroad an organised force to represent the country.

'Patriotic men wanted to show their mettle in a scrap and to demonstrate the country's unswerving loyalty to Mother Britain (ibid 285).

In the South African War New Zealand contributed 6,500 men and over £113,000 of public donations. (287) Maori were not allowed to enlist as a contingent but some managed to enlist as individuals.

Overall, 59 men died in the South African War and 160 died of the effects of disease, accidents and wounds. (289)

About 50 memorials were raised to the South African War in New Zealand: 'All but one were completed within six years of peace. The memorials preserve in stone the imperial sentiments which

inspired New Zealand's involvement in the war' (see NZ

History).

The New Zealand troops went as volunteers and had to buy their own kit and quickly gained a reputation as effective 'rough riders' and 'troopers' - 'rugged, enterprising and ready to throw away the rule book' (292) - in an emerging tradition of amateur soldiering in the increasingly guerrilla war with the Boers.

Jingoism and intolerance of dissent ran high in New Zealand and the war and its celebration provided a strong unifying theme of nascent Kiwi nationalism in remote and sparsely settled areas

(290).

The NZ Expeditionary Force

On August 4, 1914 the British Empire declared war on the Central Powers. New Zealand legislators immediately responded with the offer of an Expeditionary Force on 5th August. This was

accepted seven days later. The main body of the NZEF sailed from Wellington on 16th October under the belief they would be fighting on the Western Front. The NZEF included a 439-strong Maori

contingent (296).

But the entry of the Ottoman Empire into the war changed that and after training in Egypt with the Australian force the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps were formed. There was a fabulous fracas in Cairo - the Battle of the Waza on good Friday 1915 over adulterated alcohol, high prices and the isolation of troop with VD in special compounds (296-7) before the troops were shipped to Lemnos and from there to Gallipoli in the Dardanelles.

Gallipoli

The landing was a disaster and one in five of the 3,000 NZ troops landed on the first day - 25th April - became casualties. A terrible stalemate began with the ANZAC troops pinned down in a small

bay or on the precipitous slopes and cliffs surrounding it. Heat; dust, flies, dysentery and superior Turkish firepower and then the intense cold of winter forced an evacuation in mid-December

1915.

The Anzacs were not alone in the slaughter. Over 400,000 British and 79,000 French troops were committed to the campaign and half of these became casualties. Amongst the New Zealand contingent

the casualty rate reached a staggering 88 per cent and of the 8,450 men committed 2,721 died.

The defeat at Gallipoli and the posting of long lists of the dead in New Zealand and Australia created a trauma that transformed Galipoli into a 'sacred' experience (300). For the next three generations Anzac Day became 'the focal point of national mourning for all wars, and for the expression of patriotism' (300.)

New Zealand's losses continued as new contingents were sent to the Western Front and the Middle East. New Zealand's contribution was massive and in proportion only second to that of

Britain. 20 per cent of eligible manpower was recruited, 100,000 of a population of 1 million were sent overseas, and 18,166 were killed and more than 41,000 injured.(303) Nearly all the fallen were buried

overseas and a third

of those who were killed have no known grave.

Walking around the film set and actors outside the Auckland War Memorial Museum (as it is called) I was struck by the youth and innocence of the 'soldiers' - they were little more than boys in

ill-fitting uniforms and felt hats. And the bayonette dummies were a cold reminder of the harsh terrors of the First World War on a balmy Auckland day.

The Museum is a great place and I was really there for the Maori and Polynesian sections. But after scampering around taking as many photographs as I could I rushed upstairs to look at the other

sections. On the top floor and absolutely alone I stumbled into the long hall of the war memorial, with its muted light, flags and engraved marble slabs with the names of the fallen. It was

hugely impressive, almost as if I had wandered into a private and hallowed room of grief (which of course it is but in a more public way).

Funnily enough, and really surprisingly, the word 'Maori' does not occur on the three Museum website pages explaining the War Memorial. Even through the altar in the Hall of Memories is inscribed with the Maori, "Kia Mate Toa", meaning "be strong in death".

There is a memorial to the New Zealand Wars in one of the alcoves but I missed this.

Also, rather strangely, the bulk of the Museum building, completed in 1929, is made of English Portland Stone. (see here for more on building stone in New Zealand. It is

apparently, 'constructed on a site of significance to Maori, previously known as Pukekawa' but one wonders if this was a deliberate embracing

Maori significance or an obliteration of it. The New Zealand Heritage site listing makes much of Maori links with the use of 'Maori and native botanical motifs' in the interior and the

housing of 'Maori artefacts'.

There are over 500 public memorials to the IWW in New Zealand.

The New Zealand Wars Memorials

Thee are 74 memorials on the national memorial register to The New Zealand Wars.

'The erection of memorials took more than a century and reveals a fascinating chronology of different motives and people.'

During the Wars: 1843–1872

Only three memorials were erected during the wars. This lack of memorialisation sprang from firstly, the novelty of the idea of commemorating ordinary soldiers which started with memorials put up in Britain to the dead of the Crimean War of the 1850s. And secondly, the Pākehā community did not want to celebrate or commemorate the New Zealand Wars. The conflict had been frustrating with few clear-cut victories often at the hands of imperial soldiers rather than locals.

'People preferred to forget, rather than remember, painful and somewhat embarrassing events.'

It was a funny little dirty war with little glory that ultimately pitted the technological and organisational might of the British Empire against an indigenous people armed with little more than

hand weapons. (my words)

1872–1905 The War people preferred to forget

One rotting memorial was replaced.

1906–1920

In this period more than 20 memorials were built. This was due to:

- a widespread desire by Pākehā New Zealanders to recall early settlers and soldiers in stone monuments;

- erecting memorials served to raise consciousness of military obligations to the Empire in the face of the growing German threat;

- The 50th anniversary of the New Zealand Wars helped turn people’s attention back to the wars;

- And veterans were keen that their efforts and those of their mates should not be forgotten.

1925–1930

This period saw 12 memorials erected as in part a response to the experience of building memorials to the Great War. and in part to new interest in the NZ Wars through the publication of a

history of them and a film by Rudall Hayward, Rewi’s Last Stand.

As far as I can tell none of the memorials so far built commemorated the Maori 'opposition' although Maori who fought alongside Pakeha were sometimes remembered.

1950–

The Historic Places Trust established in 1954 put up markers and plaques at significant battle sites and raised awareness of the Wars.

'From the 1970s the emergence of Māori radicalism raised new questions about how the New Zealand Wars had been memorialised. In some places, such as St Mary’s church in New Plymouth, new memorials were put up which acknowledged the pain on both sides. In other places, such as the Wakefield Street monument in Auckland and the soldier memorial on Marsland Hill in New Plymouth, significant damage was done to monuments by a new generation expressing its resentment at the imperial sentiments carved in stone.'

In recent times the Heritage Operations unit of the Ministry for Culture and Heritage has maintained and restored government-owned memorials. And in 2002 the unit was responsible for erecting the Katikara memorial in Taranaki, the most recent government-funded New Zealand Wars memorial.

From NZ History Net written by Jock Philips

The New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars raged on and off between 1845 and 1872 and beyond. In total as many as 2,100 Maori may have been killed against 800 Europeans. The war added to the

sharp decline of the Maori population from 56,000 in 1857-8 to 42,000 in 1896 (King, History of New Zealand: 224) Taking the 1857-8 total Maori population the deaths accounted for 3.75% of the

population. Compare this to the loss in the IWW of 18,166 lives against a total population of 1m - a population loss of 1.82%.

Strange then that the grievous losses of Maori iwi are not remembered in national and local memorials and the trauma of this terrible war is not granted the 'sacredness' that was later accorded to the troops at Gallipoli and on the Western Front.

It is said by some that the Memorial at the Auckland Museum (see photo above) is a memory of European and Maori losses and yet the epitaph on the memorial seems to belie this when it says through the war 'they [the fallen on both sides] won the peace we know.'

For the 'peace that was won' was overwhelmingly at the cost of Maori in terms of lives, loss of land, the decimation of the population, (actually a fifth rather than a tenth of the population was lost) and the further marginalisation of Maori into rural wretchedness.

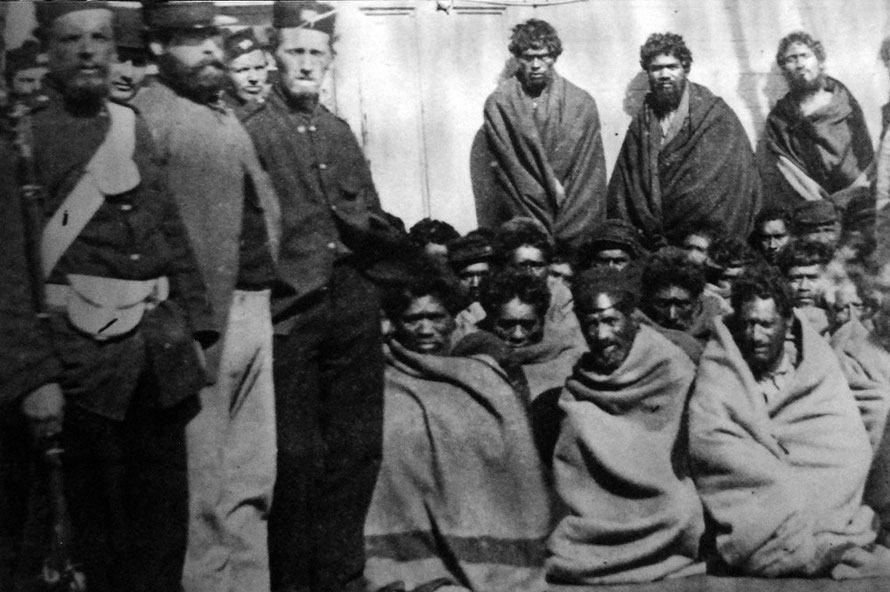

At the peak of hostilities in the 1860s, 18,000 British troops, supported by artillery, cavalry and local militia and so-called 'kupapa' Maori , (loyalists to the Empire and Queen Victoria or 'Queenites') battled about 4000 Māori warriors in what became a gross imbalance of manpower and weaponry.

The two flags on the memorial are the Empire flag and the Gate Pa flag. The Gate Pa flag was the flag of the 230 rebel Maori under the command of Rawiri Puhirake (King, History of New Zealand: 216).

More than 4m acres (16,000 sq km) of land was confiscated from Maori iwi during and after the New Zealand Wars.

'Although about half of this was subsequently paid for or returned to Māori control, it was often not returned to its original owners.'

There are strong parallels between the New Zealand Wars and the wars to create new room for settlement in South Africa. Both were motivated by a need to put the 'natives' in their place as new waves of European settlers created pressure for land appropriations that went against earlier settlements. In both there was also a turn to syncretic and messianic religious beliefs and charismatic leaders as the traditional structures and ways of live were threatened.

A great difference between South Africa and New Zealand was that it was widely believed in New Zealand that the New Zealand Wars and the devastation brought by European disease would eventually cause the Maori peoples to disappear entirely with the paternalistic and exterminating white race having a duty to 'smooth the pillow of a dying race' (see King, History of New Zealand, 224).

In South Africa the black African peoples were never a minority and except for the deliberate extermination of the Koikoi they remained a preoccupying problem for the white settler community. That the horrors of apartheid did not emerge in New Zealand is perhaps less to do with the 'kindness' of the European settler/British Empire regime than to the growing insignificance of and control exercised over the Maori population.

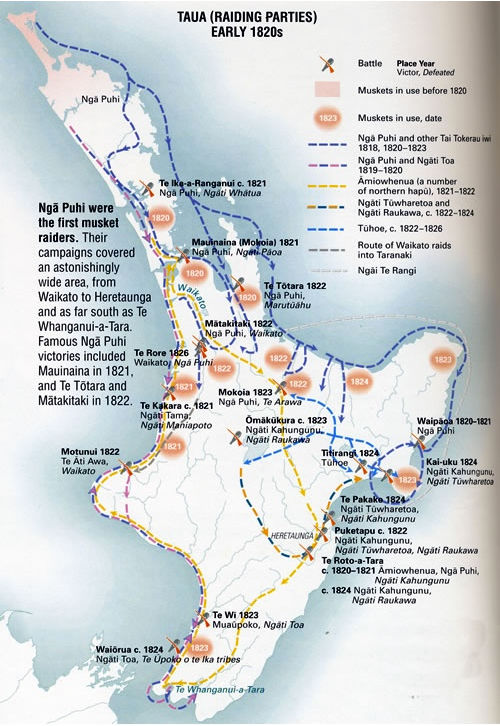

The Musket Wars

The 'Musket Wars' as they are most usually known, were a series of bloody conflicts between Maori iwi

and hapu in the first half of the 19th century - between 1818 and the 1830s. It is estimated they lead to the violent death of 20,000 Maori from a total population of New Zealand of around

100,000. And 30,000 Maori were enslaved or forced to migrate to new areas by other Maori.

It is argued that two European innovations made the scale and extent of these fatalities possible. One was the musket (and the introduction of steel for axes etc) which increased the killing efficacy of the Moari who had previously been equipped with stone and ivory clubs and spears but no projectile weapons (neither bow and arrows nor boomerangs).

This efficacy was increased by the efficiency of killing someone with a gun rather than having to overcome their resistance and manually club them to death and the sudden obsolescence of the

defences in the fortified pallisades of the pa which were not designed to withstand musket fire (This was something that was quickly remedied). The replacement of the hand-to-hand fighting with

the musket (which was effective for a range of about 40 metres (ref?) also allowed a distancing of the act of killing and gave it an immediacy and finality that was perhaps lessened the more

ritualised warfare of pre-European Moairi violent conflict.

Muskets were obtained through trading with the Europeans and as the arms race between iwi and hapu took off agricultural production had to be ramped up to secure muskets which were initially

very

expensive - costing for example - 200 baskets of potatoes or up to 15 pigs.

The other innovation was the introduction of the red-skinned American sweet potato and the Latin American potato which had been long naturalised in Europe. Previous to this Maori cultivated the Polynesian sweet potato - the yellow-skinned kumara - but these only grew to the size of a man's finger.

The potato was particularly advantageous because it could grow in a wider climate range than the kumara and it provided greater amounts of carbohydrate than the kumara - it was both easier to cultivate and produced greater crops (I think). I think the argument is that by being able to accumulate greater stockpiles/surpluses of easily processed carbohydrate Maori iwi were able to supply and organise larger and larger raiding and war parties (taua and muru - a war expedition to honour the death of an important chief) over longer distances.

The potato was also hugely important because it was something that was desired by whaling crews and it became a key tradeable currency with whalers and sealers for muskets. The need to acquire muskets in itself then put an increased value on securing sufficient fertile land or harvested crops to pay European settlers for them.

The opportunities presented by the arrival of Pākehā (European) traders, whalers, and timber and flax millers at places such as the Bay of Islands ... attracted Māori to these areas, often from great distances. Ngāpuhi in particular benefited from their early contact with Europeans by securing access to firearms, which they used in raids on other tribes (Wikipedia: Musket Wars).

So it wasn't just the technologies that were part of the conditions of possibility of the Musket Wars but the particular presence and location of traders and settlers and the relationships that particular Maori iwi, hapu and leaders established with this presence.

This was particularly the case with the leader of the Ngaipuhi, Hongi Hika, who travelled to Sydney to make links with missionaries whose presence in turn engendered more trade and stability. Hongi eventually travelled to the UK, met King George, went to Cambridge to help establish the first Maori-English dictionary and returned, via Australia, where he sold of his gifts (other than a sit of armour) in exchange for 300 muskets.

The development of 'Pakeha Maori' communities and families resulting from inter-marriage was also vital for passing on skills and trading relations, contacts and by-passing the missionaries who were - unsurprisingly - unwilling to provide muskets (Wikipedia: Musket Wars).

Here the particular administrative and legal forms of early settlement and trade relations are also key. In New Zealand these seemed particularly open and laissez faire and took place between individual traders (whalers, sealers, adventurers) and Maori and Pakeha Maori families and social networks in the context of their hapu and iwi.

Looking at the early settlement of South Africa at the Cape (see my pages here) this was done under the aegis of the East India Company to create a supply station that gradually grew into its hinterland. It was accompanied by widespread

slavery - whether indigenous or with slaves imported from locations along the East India Company sea lanes (Madagascar and Malaysia). From recollection there was never an easy route

for muskets to pass to rebellious indigenes given that overall governance was supplied by the all-powerful East India Company. Instead, at least with regard to the Koi and San peoples they were

mercilessly gunned down into practical extinction.

Closer to New Zealand you wonder why guns did not get into the hands of Aborigines. Presumably this was to do with the strict regulation of settlement effected under the penal colony that marked

the origins of Australia's European settlement and perhaps also due to the the limited trading possibilities open to Aborigines as well as prevailing racist attitudes.

You wonder how much events like the Musket Wars also coloured the European perception of Maori as a war-like people. This seems to have been admired as a good 'noble savage' quality. But how much

has the notion and narrative of Maori-dom been reduced and focussed onto these war-like qualities - which were hugely exacerbated by the introduction of the musket and favourable trading

relations with particular iwi - and further burnished in the ignoble New Zealand Wars where the plucky 'noble savages' were outnumbered and outgunned by Imperial troops and local

militia.

In this light the rise of the Maori haka, which was often performed at the outset of war parties, as the pre-eminent global marker and brand of contemporary Maoridom is instructive if not ironic.

Instructive in that 700 years of Maori presence is reduced to a war dance and ironic because the bringers of the technologies and stimulus to greater and more destructive wars were European and

yet they rarely acknowledge this by the belligerent spectacle of a 'primitive' war dance.

Perhaps the most important outcome of the musket wars was the bitter legacy of inter-hapū and -iwi mistrust stemming from the extreme violence with which they were fought. The constant use of treachery as a battlefield tactic, coupled with the enslavement of so many, left a long legacy of mistrust. (Wikipedia: Musket Wars)

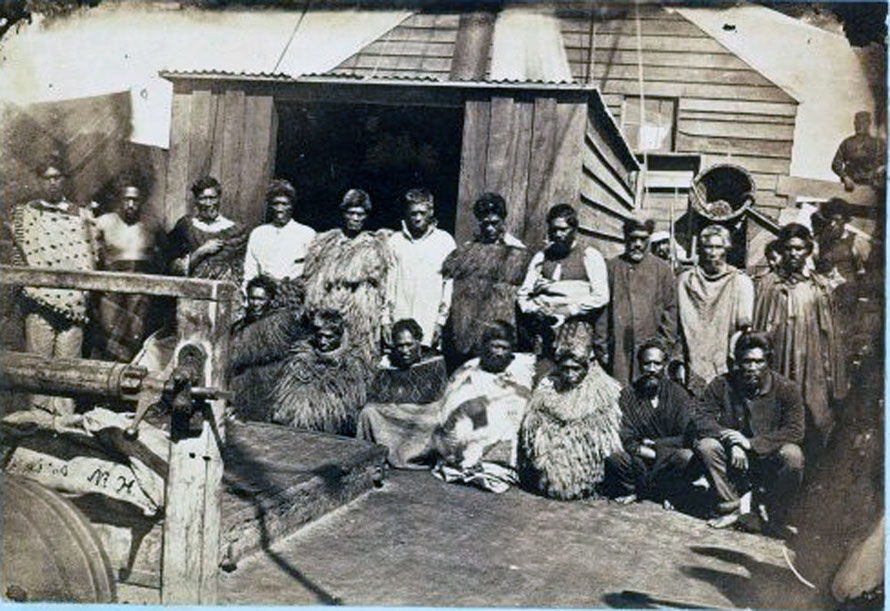

The divided, decimated and displaced Maori population and its tribal and (inter-tribal?) structures were thrown into confusion. Missionaries often acted as mediators and evangelising within the Maori population gathered pace. Shortly after the end of the Musket Wars - with internal divisions and mistrust at a maximum - the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in different places and at different times between the Crown and the different leaders of Maori iwi.

The Musket Wars may also have increased pressure to turn New Zealand into a colony of the British Empire as administrators were troubled by the supply of muskets to Maori.

Between 1845 and 1847 three acts were passed to stop the sale of guns to Maori with severe penalties. But in 1857 a law was passed allowing Maori to have guns for sporting purposes. This lead to a huge accumulation of guns by Maori largely to defend themselves against other Maori. Nevertheless the guns would come in handy should war break out - as it did in the New Zealand Wars - between Pakeha and Maori. The subsequent 1869 Firearms Amendments Act made it illegal - punishable by death - to sell weapons to a Maori in rebellion. (Wikipedia: Musket Wars).

You wonder also how the Musket Wars contributed to the popular view of Maori with the murderous campaign, the mass enslavements, the subterfuge and treachery, summary killings and widespread ritual consumption (cannibalism) of slaughtered enemies. Was there a shift from the 'noble savage' to the murderous, cunning, well-armed savage' that raised perceptions of threat levels and put new strategies on the table with regard to the 'Maori question'?

Sources for this Musket Wars section - King, Wikipedia Musket Wars and Taua, Te Ara The Musket Wars and NZHistory.Net

Want a quick summary? Watch this handy video made by D E.

Why did Maori fight?

(more to do on this section - were Maori more 'warfaring' than other preindustrial peoples? than other Polynesians? What was the dynamic of intra-Maori conflict prior to the arrival of

Europeans?)

'These wars have been described as a prime example of fatal impact theory in practice' NZ History.net

For control of land, food supplies and particularly stored food and other resources.

For mana (prestige, psychic authority)

For revenge - utu (returning balance)

For women

For the sheer hell of it (McClean)

'He wāhine, he whenua, e ngaro ai te tangata' (Through women and land do men die). (Te Ara:Making War )

Pa (a fortified stockade often with a food storage area) first become apparent in the 15th century - two hundred years after the first Maori presence in New Zealand. The many thousands constructed were almost always co-located with Maori food gardens. The pa underwent big changes as the musket became the weapon of Maori warfare and were reinforced to offer protection from musket fire and to provide firing positions for defenders.

Maori violent conflict was hand-to-hand using a limited range of spears and clubs. These were often painstakingly made and considered as treasure (taonga) and handed down from one generation to

the next and often acquired a particular name - Weapons were often considered tapu - sacred - and incatations were said over them and warriors before battle. Young men were schooled in the

art of fighting and weapon use in para whakawai (weapons training school) (see Te Ara: Mau rakua).

It was a from of ritualised conflict. But as land pressures grew with both a rising Maori population, theextinction of the moa as a source of easy protein, and advancing European settlement

tensions grew and 'insults demanding a response multiplied' (see here NZHistory.net).

The Trojans had their horse but some Maori - the Kgati Kuri - has the whale - a fabricated whale that resembled a stranded pilot whale (a valuable source of food and bone/teeth) that concealed a hundred warriors. Subterfuge and surprise were important in Maori armed conflict as one group would often be within their fortified pa.