V. Ulva Island/Te Wharawhara, Stewart Island

Introduction

The main part of this page is a photographic journey through Ulva Island - the jewel of Stewart Island and one of the jewels of New Zealand. However, I have also written a few notes on the history, people, climate, geology and forests of Ulva - which touches on the broader history of Stewart Island/Rakiura.

My plant identifications always need to be taken with a pinch of salt although I make every effort to get them right and have benefited from Peter Tait's knowledge and insight.

History

The part of the history of Ulva Island that is in many ways really remarkable is its lack of human history.

The first humans to settle in New Zealand were Maori, who arrived in the 13th century AD. Before this there had been no human presence on New Zealand whatever.

Ulva Island does have a short and interesting human history but even this has had a minor impact on the island and its podocarp and hardwood forests, most of which have never been felled.

Predators and browsers did arrive on the island and indeed its European settlers made efforts to bring in plants and animals from elsewhere. By the same token the great birds of New Zealand's land-mammal-free evolution are long gone. The flightless parrot, the kakapo/night parrot (Strigops habroptilus), was rediscovered on Stewart Island in the 1970s when thought extinct and is now in a critical recovery programme on more distant islands with 126 or so thought to be extant.

Maori

Ulva Island was visited periodically by Ngāi Tahu Māori to strip bark from tōtara trees for use in storing muttonbirds/tītī (Sooty Shearwaters). It was known as Te Wharawhara. (For the process of storing titi see this page.)

Astelia banksii is now associated with the name 'Wharawhara' but it only grows on the North Island. The plant associated with the Maori name was more likely the Bush Lily, (astelia fragrans) that grows on the forest floor on Ulva Island.

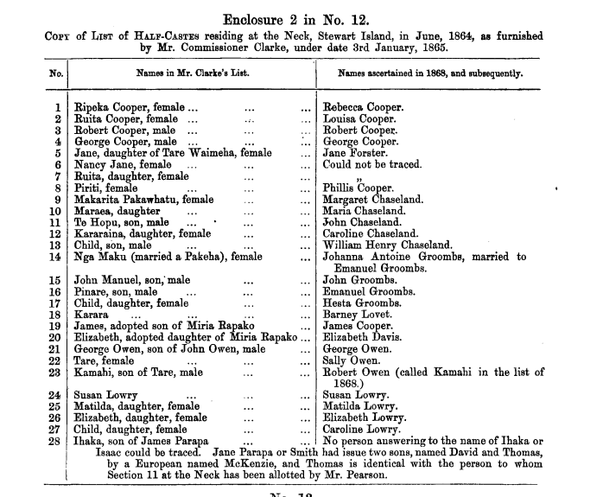

There was a Maori settlement on The Neck/Onecki (across the waters of Paterson Inlet from Ulva) for over 700 years. In 1846 the population had reached sixty as whalers and sealers intermarried with Maori. The Crown purchased Stewart Island/Rakiura in 1864 and The Neck/Onecki 'was reserved for half-caste [mixed-descent family] settlement' and somewhat belatedly land was allocated to all those who could prove they were 'half-caste' - although 'three-quarter caste' were excluded from this settlement (see Rakiura Maori Land Trust and NZ Government Papers - excerpt below).

Men received 10 acres and women eight. A school was built in 1878 and had a roll of 30. The settlement is thought to have grown to about 200 people by about 1900. By 1920 it was virtually deserted.

Charles Fraill's (see below) brother, Arthur, taught at the 'Native School' on the Neck until 1887 and Charles' wife, Henrietta Jessie Bucholz was revered for her good works there.

The Rakiura Maori Land Trust administers land on The Neck which is held by some 1,200 Maori descendants.

See the interesting biography of Wharetutu Anne Newton, one of the first Ngai Tahu women to marry a pakeha husband on Stewart Island (Te Ara: Newtoni) and the biography of Ngai Tahu chieftain, Te Whakataupuka, who made his base on Ruapuke Island in the middle of the Foveaux Strait and later led a war party on the Otago Peninsula against the Wellers' whaling station (see my page: The Travails of the Ngai Tahu).

Europeans

Europeans - Scottish northern islanders and others - started to arrive in the early 1800s as sealers and whalers and many settled at The Neck and Pegasus Bay.

Later attempts were made at sheep farming but the wet, infertile soils and dense forest cover proved discouraging. Logging was more successful, particularly in Paterson Inlet and fishing later came to dominate the local economy before tourist numbers built up to the current 30,000 visitors a year (see Te Ara: Stewart Island).

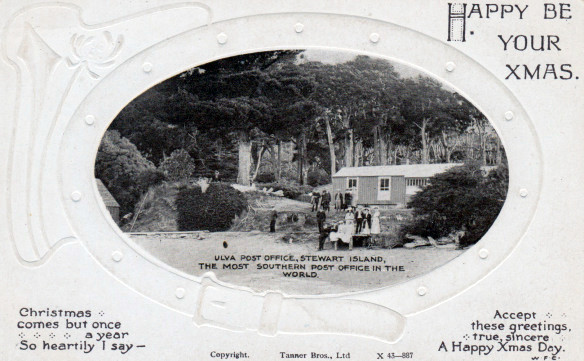

In 1872 Charles Traill established the first post office - known as 'Paterson Inlet Post Office' - in the Stewart Island region at Post Office Bay on Ulva. The island was a central point in Paterson Inlet and Traill was able to alert the scattered community around the inlet to the arrival of the mail boat by raising a flag. Ulva Island became a social meeting place for locals. The post office closed in 1923.

Ulva Island was formerly called 'Coupars Island', after Stewart Coupar, a sealer who settled nearby on The Neck. Charles Traill changed it to 'Ulva' although as far as I can see there is not an Ulva Island in the Orkneys.

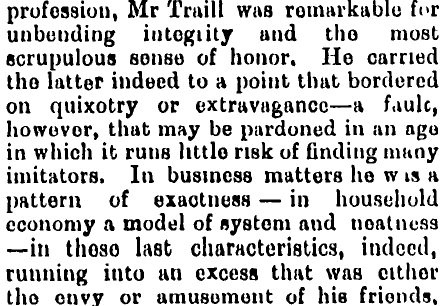

There is a fascinating obituary of Charles Trail from the Southland Times. Charles died on 26 November 1891 on Ulva Island aged 66. It states that the family of the Traills of Woodwick, Orkney was 'an old and distinguished one'. (The Traills of Orkney appear to have been a family of lairds and bishops according to this geneology site entry.)

Educated at Edinburgh University and apprenticed to a lawyer (see www.nzbotanicalsociety.org.nz and Historygeek) Traill left Scotland to have a go at sheep-farming in Australia in 1849.

In 1850 he left Australian sheep-farming for the California goldrush and battled fever and ague for three years. Returning to the UK he left for New Zealand in 1856 and set up a mercantile firm of Traill, Roxby and Co in Oamaru. This was 'dissolved' and Traill repaired to Stewart Island to purse a business in fish-curing in 1871.

The fish-curing business 'did not answer his expectations' (see Obituary above) and Charles bought land on Coupars Island and renamed it 'Ulva'. Here he established a post office where he became postmaster and storekeeper.

He married Danish-born Henrietta Jessie Bucholz 'a lady whose efforts on behalf the natives at The Neck and in the island of Bravo are still held in affectionate remembrance' (see Obituary above).

She died in 1875 when their daughter Ellen was only three. Although 'fitted for higher things' Charles went on to 'beautify' his part of Ulva with carefully collected native New Zealand shrubs. He peopled it with 'English singing birds'.

A renowned conchologist and botanist and with strong Christian beliefs he sometimes amused his fellow islanders with his strict practices (see excerpt from Obituary below). He was survived by a daughter and his two half-brothers who lived on Stewart Island (see below).

Charles Fraill and his wife are buried on Ulva. Robert Paulin, a surveyor and civil engineer of Dunedin who visited

Fraill a number of times called him 'a gentleman of considerable scientific acquirements' and 'the only honest storekeeper I ever met in the colonies' (see www.nzbotanicalsociety.org.nz).

A message entry on a genealogy site from a Lyn Traill in Australia says:

I'm a descendant from the Orkney Traill. My great-grandfather Charles Traill migrated to New Zealand via the Californian goldfields in the 1850s and settled on a small island in the far south of New Zealand named Ulva (near Stewart Island). His daughter, Ellen Traill married Charles Augustus Drew in Melbourne, Australia. They were my father's parents.

Charles Traill's life finds echoes in that of Felix Authur Douglas Cox (1837-1915), a Rugby-educated Englishman who became a sheep-farmer and noted botanist (amongst his others natural history skills) on the Chatham Islands. He briefly met Fraill when he visited the Chatham's whilst looking for a sheep run (see History Geek for details. Cox's obituary is here).

Walter Traill, (1850-1924) also a half-brother of Charles was brought up in St Andrews, on the Fife coast of Scotland, and attended Madras College (amazingly the admittedly up-market state comprehensive school that 'The Principal' - my partner - attended in the 1980s).

Walter was a sealer and sailor (first mate) and sailed the world before returning to live with Charles on Ulva. After Charles' death he took over the running of the post office, probably until it closed in 1923. He died in Southland hospital in 1924 and is buried in Invercargill (see www.nzbotanicalsociety.org.nz).

Charles' half-brother Arthur Fraill (1852-1936) taught at the Native School on The Neck. Arthur retired from teaching in 1887 and moved with his family to nearby Ringaringa on the 'mainland' of Stewart Island close to Oban.

Between 1888 and 1902 he held 'Run 425', a 900 acre sheep run near the mouth of the Rakeahua River. He chaired the Stewart Island County Council in 1904-05 and later moved with his wife Gretchen (the daughter of a German missionary, JFH Wohlers of Ruapuke Island) to "Woodwick" in nearby Leask's Bay where they had a 'splendid garden'. He is buried on Ringaringa at the Traill-Wohlers family plot near the Wohlers Monument (see www.nzbotanicalsociety.org.nz).

Roy (Robert Henry) Traill, one of three sons of Authur and Gretchen fought in the IWW and eventually returned to Stewart Island in 1925 as a part-time ranger for the State Forest Service and the Department of Lands. He claimed that, ‘the most valuable thing I did was to stop respectable people from helping themselves to the birds’ of the the island.' He was a self taught bush botanist and helped early botonaists explore and document the island's flora and fauna. Made an MBE in 1963 he died in Riverton Hospital in 1989 aged 96 (see Te Ara: Rob Traill).

There is a fascinating brief account of the Rev. Johann Wohlers life on Ruapuke Island by his great grand-daughter, Sheila Traill, on the fergusontree.com genealogy site.

Ruapuke Island is in the middle of the Foveaux Strait. Wohlers wrote an account of his life published in English in 1895 as Memories of the life of J. F. H. Wohlers. It is online here at archive.com.

Says History Geek of New Zealand,

In the 1890′s and early 1900′s increasing numbers of tourists visited Traill’s picturesque island in Paterson Inlet ... [via] steamship tours of Stewart Island and Fiordland ... Ulva Island’s natural beauty and its quaint post office were a highlight for many of these southern tourists, some of whom were greeted by Charles’ brother Walter.

Postcards were not the only thing sent from the post office. Posted messages on leaves became a craze in the early 1900s. These were the dried leaves of the shrub Rangiora that at the time went under the latin moniker of Senicio reinoldi and was later renamed to the chagrin of some (for the removal of the reference to the NZ botantist, Johan Reinhold Forster) to Brachyglottis rotundifolia. This shrub grows in abundance on Ulva Island.

The NZ Post Office tried to ban the use of leaf-postcards with circulars in 1906, 1912 and 1915 (see pukeariki.com) with little result. The leaf-postcard trade from Ulva's Paterson Inlet PO finished with the closure of the post office on Ulva in 1923.

The Climate and Geography of Ulva Island

Position and Latitude

Ulva Island sits in the sheltered Paterson Inlet/Whaka a Te Wera on the eastern side of Stewart Island/Rakiura. Paterson inlet is a ria - a flooded river valley.

The island is 3.5 km (2.17 miles) long and has an area of about 270 hectares (670 acres), the majority of which is part of Rakiura/Stewart Island National Park.

Ulva Island lies between latitudes south 46 and 47. For comparison Nantes in France, which sits at the the mouth of the Loire is at 47 degrees north and La Rochelle on the Atlantic ocean in south-central France is at 46 degrees north.

Snowfall and frosts are uncommon but not unknown (five mornings with obserevable frost a year, says Peter Tait of sailsashore.co.nz). Mean annual temperature is 8-10C and annual sunshine hours are low for New Zealand (1,400-1,600) compared to 2,200-2,600 for Golden Bay. (Nantes in France gets about 2000 hours.)

Prevailing winds are westerly and north westerly although it appears that Wellington gets more gale days over 33 knots than Stewart Island (see this summary of Southland weather).

For the daily weather see the webcam on Stewart Island here at

www.sailsashore.co.nz

A Comparator: the West Cost of Scotland climate (with 50% more rain)

In terms of climate Ulva Island might be said to have a 'low-lying west coast of Scotland' type of maritime-temperate climate. Mean temperature there is 9.5C, annnual sunshine at the Mull of Kintyre approachs 1450 hours and prevailing winds are south-westerly and north-westerly and lowland coastal rainfall is about 1000mm a year. Even sea surface temperatures are roughly similar - Saber Reef at Stewart Island has an average annual surface temperature of 11C and Riverton on the Soutland Coast is 12.61C while Ayr on the west coast of Scotland (excellent global world sea temps site here) is 11C.

The one big difference is rainfall which is nearly 50% more on Stewart Island compared to rainfall on the lowland west coast of Scotland.

The fact that these climates are so similar despite a nine degree difference in latitude (Glasgow 55.8N) attests to the massive influence of the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Drift in the north western Atlantic which raises air and sea temperatures a couple of degrees above their latitudinal average, particularly on west coasts.

It also attests to the cooling influence of the southern oceans on Stewart Island summer temperatures. For example, Comodoro Rivadavia at latitude 45.5 S on the coast of Patagonia has a semi-arid climate with just 189mm of annual rainfall, an average daily mean temperature of 13.1C and a January average high of 26C.

Geomorphology

Ulva Island is made up of a series of low lying, undulating and gently sloping ridges that reach a maximum elevation of 72m. The shore line is heavily indented and made up of narrow inlets, broad sandy beaches and rocky bays and coastline.

It is surrounded by some of the cleanest and clearest saltwater and brackish water in the world. This is due to the uninhabited character of most of Stewart Island such that runoff into Paterson Inlet is remarkably unpolluted and free of sediment overloads. The immediate waters off the island are a Marine Reserve and host a remarkable diversity of fish, seaweeds and shellfish.

The rocks of Stewart Island form part of the Median Batholith of plutonic basement rocks formed of granite and granitoid intrusions. They stand far enough away from the undersea continuation of the Alpine Fault to not have been greatly affected by tectonic activity.

This gives rise to relatively gently sloping rounded hills with the poor drainage associated with granite country. Deep beds of rotten (in the UK 'bastardised) granite

creates problems with slope stability where roads have been cut through the steep hills around Halfmoon Bay (Oban).

The Median Batholith formed way before the separation of the Zealandia sub-continent from Gondwana (80 MYA) and is,

'assumed to represent a long lived (Late Devonian-Early Cretaceous, 375-110 Ma) Cordilleran batholith, corresponding to a subduction zone along the margin of eastern Australia, before the formation of the Tasman Sea (83-55 Ma).

A 'batholith' (from Greek bathos, depth + lithos, rock) is a large emplacement of igneous intrusive (also called plutonic) rock that forms from cooled magma deep in the Earth's crust Wikipedia: Batholith.

Erosion processes in exposed batholiths are not only caused by normal weathering forces but also by,

[the] huge pressure differences between their former location deep in the earth and their new location at or near the surface. As a result, their crystal structure expands slightly and over time. This manifests itself by a form of mass wasting called exfoliation.

These pressure difference and crystal growth presumably accentuates processes that lead to granite rot and bastardisatiion.

For the geology of the rocks see Allibone, A.H., and Tulloch, A.J. (2004) Geology of the plutonic basement rocks of Stewart Island, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics, 47 (2). pp. 233-256.

Forest type

Ulva is one of the very few areas of podocarp forest in New Zealand that is largely undisturbed.

Apart from felling around the Post Office site the island was never subject to other tree felling and after petitioning of the government in 1899 by Charles Fraill (who owned seven hectares of the island) it became 'A Reserve for the Preservation of Native Game and Flora' (Tait below).

However, Ulva sits at the southern limit of Podocarp growth. Rimu do well and dominate. Miro are common but the majority show signs of malformation and wind shake. Hall's Totara are numerous but seriously deformed due to climate stress. They also suffer greatly from the depredations of Kaka where bark is stripped back to find insects and encourage sap flows for food.

Kaka attack is natural but with the island rid of rats the Kaka population is on the rebound. Even Rimu suffer attacks (see Peter Tait's summary of the state of Ulva's forest).

A 2008 invertebrate study found three dominant and distinctive habitat types on Ulva:

(1) coastal scrub dominated by Brachyglottis rotundifolia (mutton-bird scrub), Dracophyllum longifolium (inaka), Gahnia procera, and Olearia colensoi (leatherwood);

(2) coastal broadleaf forest of Metrosideros umbellata (southern rata), Wein- mannia racemosa (kamahi), Griselinia littoralis (broadleaf) and occasional Fuchsia excorticata and Dicksonia squarrosa (tree fern);

(3) podocarp forest dominated by Prumnopitys ferruginea (miro) and Podocarpus hallii (hall’s totara) with a dense bryophyte ground cover (Michel 2006)

(See Michel.P, et al 2008 'Invertebrate survey of coastal habitats and podocarp forest on Ulva Island, Rakiura National Park, New Zealand', NZ Journal of Zoology 2008 Vo.35. p.336).

Peter Tait (above) reports that kamahi on Ulva suffers badly from salt-laden winds and has been knocked back by recent bad winters.

Introduced species

White-tailed deer were introduced to Stewart Island in 1905 and eventually swam across to Ulva. Here they did huge damage grazing on understory and coastal shrubs. Rats also infested the island although the possum (released on Stewart Island in late 19th century) never got to Ulva.

The eradication of deer was carried out by hand-painting 1080 pesticide paste onto shrub leaves browsed by the deer. Rat were finally eradicated in 1977.

Since then the understory and regeneration have improved hugely and certain species, like Lancewood, where seed was eaten by rats, have made a remarkable recoverey(see Tait above).

Once cleared of introduced predators birds were reintroduced to the island. These include the South Island saddleback (tieke), yellowhead (mohua) and Stewart Island robin (toutouwai). Other birds on the island that are rare on the mainland include the Stewart Island Brown Kiwi (tokoeka), Rifleman (Tītitipounamu), Yellow-crowned and Red-fronted Parakeet, and South Island Kākā or forest parrot, as well as several other species (Wikipedia).

Impressions

The forest on Ulva feels very different from the beech forests of Milford and the rata/kamahi forest of Fox Glacier. In fact, it was amazing to walk in a mature forest where the canopy and understory are clearly demarcated. Its the sort of place you would need to go to time and again to really get the feel of it.

But on this first outing it felt wonderful - cool, with dappled and darker shade, an undulating rocky terrain and an invigorating airy feel. And there was bird song and lots of it. I particularly remember the NZ pigeons - kereru - high up in the rimu and totara canopy, the wheka, the amazingly tame Stewart Island Robin, and the South Island Saddlebacks.

The lack of bunged up, tangle meant it was relatively easy to see the birds and the the weka and robins came to us.

It did feel like stepping back in time, as much as that is possible and the powerful water-taxi that got us there notwithstanding. We were particularly lucky or canny to go early when for a certain fact there were only two other people on the island.

Of course there were no Moa and the Haast Eagle was not perched up in one of the giant Rimu trees. And we failed to see a Kiwi despite running to keep in front of a visitor with a booming voice oblivious to the peace and quiet she was trampling through.

We were lucky in so many ways with our visit. The weather was good, even hot. The season was late and there were few other people about. And the tide was out.

This latter good chance meant that we could briefly appreciate the diversity of marine life on Ulva's rocky and sandy intertidal zones.

The fact that a fur seal seal also decided to put on a display of octopus flailing in front of our eyes with camera loaded was yet another stroke of fortune.

An Ulva Island Photographic Journey

The rest of this page is a photographic journey around Ulva Island, completed in four short hours of frenetic activity. It starts with our journey out from Stewart Island's Golden Bay, over the hill from Oban, to Ulva by water taxi and ends with us leaving Ulva by the same water taxi.

All photos are mine but for two and all are taken on Ulva but for those of the Kaka which we saw on Stewart Island.

I would like to thank Peter Tait at www.sailsashore.co.nz on Stewart Island for his help in identifying some of the plants in these photos and for his article on the forest of Stewart Island.

Whilst I hope my brief relationship with Ulva Island will one day be renewed I feel very lucky to have been there at all and shared in its riches.

A Note on the Seal Photos

The photo sequence below is taken from West End Beach on Ulva Island. I have puzzled over the creature the seal is thrashing around.

Having looked at them again and again I wonder now if perhaps the first and second ones are a different creature from the subsequent 7 photos. The first two photos have a 2 second gap between them, then there is a 45 second gap, another 42 second gap, an 8 second gap, a 22 sec gap, a 2 sec gap and then over 10 minutes before the last two photos (sepearted by a second) - which seem to show the seal finishing off its meal.

The last seven photos definitely look like an octopus. Peter at www.sailsashore.co.nz on Stewart Island suggests it is Pinnoctopus cordiformis or wheke, New Zealand's commonest and largest octopus. He also says he has seen this process of flailing many times by local seals.

However, the second (blown up) photo just doesn't look like an octopus to me (although in the first one suckers are pretty evident). The body appears to be elongated and the tentacles look more like spines. Maybe this is just a trick of the movement.

That's the trickery of photography I guess. Tiny moments caught in time where extreme movement and speed is frozen and the time gaps between the photos get neglected or forgotten.

Ulva Island/Te Wharawhara Marine Reserve

The Paterson Inlet/Whaka ā Te Wera is a shallow ria – an ancient river valley that has been submerged – and provides one of the largest sheltered harbours in southern New Zealand.

Because the rivers that flow into it drain from pristine, undeveloped land, they carry little sediment or nutrient run-off. As a result, inlet waters nurture a prolific range of plants and animals.

Paterson Inlet is also an important habitat and nursery for at least 56 species of marine fish. The mixing of warm, subtropical and cool waters in the currents around Stewart Island/Rakiura has created an environment with similarities to both regions, and adds to the diversity of species found within the inlet.

The inlet is home to brachiopod species that live both on rock and sediment, thriving at depths of less than 20 m. This makes it one of the richest and most accessible brachiopod habitats in the world. Brachiopods (lamp shells) are the most ancient of filter feeding shellfish. They were abundant in prehistoric oceans 300 to 550 million years ago. Today their fossils are common but living examples are comparatively rare.

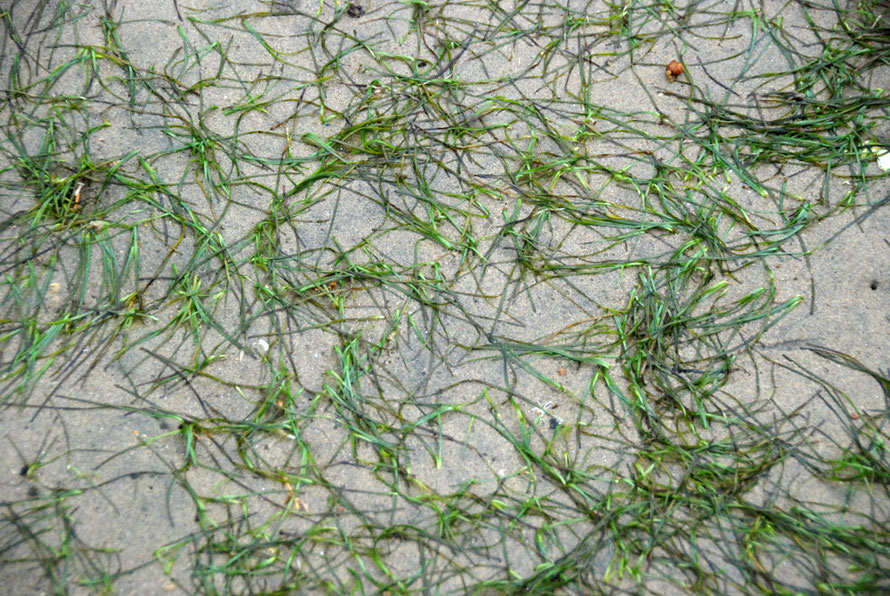

Stewart Island/Rakiura has more varieties of seaweed than anywhere else in New Zealand. Paterson Inlet is home to 70% of them, including 56 brown, 31 green and 174 red species. Meadows of small red seaweed grow on the sand. They help to stabilise sediment as well as providing an important shelter for scallops, and a surface for spat to settle on

(from DOC here).

Video

There is a rather poor resolution DOC video at the link below that gives a great sense of the richness and sub-tropical feel of the Ulva Island/Te Wharawhara Marine reserve. If you click on this you might not come back automatically to my website.

DOC video link