VII. The Rise of Maori Social Investment

Introduction

This page looks at the extent of Maori Social Investment, particularly with regard to the Maori claims settlement process under the Waitangi Tribunal.

It does this for two reasons. The first is that the settlement process asset transfers to Maori iwi were in part designed to give enough assets to start of process of collective Maori social investment - usually at the level of the iwi - that could provide an important income stream for meeting social, economic and cultural development goals.

Hopefully this section might be able to give an idea of how far those goals are being met.

Secondly, there is some concern that Maori social investment is being given unfair market advantages through beneficial tax treatment. This is done both through the differential taxation of 'Maori Authorities' (see below) and the granting of charitable status to iwi umbrella organisations under which sit their holding groups of often entirely commercial activities.

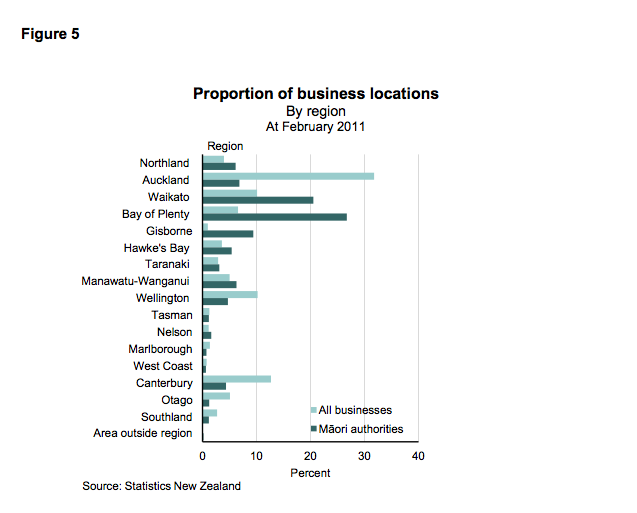

There is a very useful NZ Statistics report on Maori business, Tatauranga Umanga Māori - Statistics New Zealand May 1202 (www.stats.govt.nz). This analyses the economic significance of Maori,

trusts, incorporations, boards, Mandated Iwi organisations (MIOs), Post settlement government entities (PSGEs), and holding companies.

This obviously does not include private or publicly owned companies that are owned by individual Maori or self employed Maori. (see p.7). The data also includes 50% joint ventures with companies as defined above (P.13).

From the figures below it doesn't look like the commercial world should be quaking in its boots yet.

- Total income for Māori authorities in AES [Annual Enterprise Survey] 2010 was $1.8 billion. This was 0.3 percent of the $549.6 billion in total income for all AES industries that year.

- Total expenditure for Māori authorities in AES 2010 was $1.4 billion. This was 0.3 percent of the $497.7 billion in total expenditure for all AES industries.

- Total assets recorded for Māori authorities in AES 2010 were worth $10.0 billion. This was 0.6 percent of the $1,775.9 billion in total assets for all AES industries.

- To place the asset value of Māori business in perspective, it is similar in size to New Zealand's horticulture and fruit growing industry which had $10.3 billion of total assets in 2010.

- The number of total filled jobs in Māori authorities increased 2.6 percent for the December 2010 year, to reach 7,150.

- Exports of goods by Māori authorities were $286 million for the year ended June 2011. Total exports for the year ended June 2011 were $46.1 billion. The main export for Māori authorities was seafood.

Tatauranga Umanga Māori - Statistics New Zealand May 1202 pp.15-18

Discussion

The proportion of the enterprise economy accounted for by collective Maori firms is less than 0.5% of the national figure.

Compared to the current Maori population of half a million (11%) this figure is massively unrepresentative.

Eleven percent of the AES enterprise income figure is $60.5bn compared to the current figure for Maori collective enterprises of $1.8bn (NB This figure does not take into account Maori owned companies and self employment).

Given the very small share of Maori collectively owned firms in the national economy the argument that they threaten other commercial enterprises because of their tax breaks - either Maori Authority (17.5%) or Charitable (exempt) against a corporate tax rate of 28% - is hard to sustain at an aggregate level although there might more significant impacts in particular sectors and locations (for example property development in the South Island where Ngai Tahu Property is the biggest company on the South Island).

So maybe it is OK, not to say right, to turn a blind eye to what can appear anomalies where wholly commercial activities continue to enjoy tax exempt status because they are covered by a charitable umbrella.

This blind-eye-turning being based on the idea that these companies are critical actors in a restitution process that has at one level been grossly unfair to Maori iwi by transferring assets that in no way reflect the real losses suffered by the Crown's failure to uphold the Treaty of Waitangi ($170m against $20bn in the case of the Ngai Tahu).

Or maybe it is not 'blind-eye-turning' at all but a situation that is transparent and accountable through the various legislative acts of settlement, Maori Authority etc.

This does not reduce the imperative to provide clear and transparent governance within Maori collective enterprise however. If anything it makes the need for it stronger (why?).

A Note on 'Maori Authorities'

In 1939, 'Māori authorities' were created to act as trustees in order to administer communally-owned Māori property on behalf of individual members.

Today, a Māori authority must manage or administer assets held in common ownership. These entities may be trustees of trusts or companies.

Legislation was passed in 2003 to introduce new rules that apply to the taxation of Māori authorities. The new legislation became effective from the 2004/05 income year and replaced the existing tax rules governing Māori authorities.

All Māori organisations wanting to take advantage of the Māori authority tax rules, including the tax rate of 17.5% [as opposed to corporate tax rate of 28%], must meet the qualifying criteria and elect into the system.

The eligibility criteria that applies to TRONT.

HF 2(2)(d) A company that -

(ii) is contemplated by the deed of settlement of the claim as performing the functions referred to in subparagraph (i).

Note 1