Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu - governing social investment

NOTE: If you have come through to this page you have done well. It is hidden on my website but shows in the site map. This page is a detailed exploration of some aspects of the

governance of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

These notes are more my own musings than for public consumption and should be read with caution in that I have not fed my comments back to Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu for comment. On the other hand I have been diligent in carefully looking through the web-based resources available from Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

If you have comments please get in touch via my contact page. Cheers.

The tribal council and holding corporation set up in the wake of the Ngai Tahu Settlement looks to me rather like a big UK community development trust. The main differences are the specific focus of the activites on tribe members and the backing of the social development side of the trust by its commercial activites and assets.

Assets of just over NZ$1bn - with 76% in property and capital investments - and turnover of NZ$230.3m generated a net operating surplus of NZ$51m.

This profit stream funds the operating expenses of the tribal council (NZ$11.4m) and the distribution of funds of NZ$19.9m to the various social and cultural development activities of the council (training, education, marae development etc.).

The governance structure looks odd to UK charitable eyes. The tribal council, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, is responsible for the day-to-day management and goverance of its activites and those of commercial activities under the Ngai Tahu Holdings Corp. The governance structure of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu seems to be made up of a Board of 18 paid (c.NZ$40,000 a year plus fees for Committee chairs and overall Kaiwhakahaere/chair - Ta Mark Solomon received $250,00) elected Representatives plus the Chief Executive.

Above this there is the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Charitable Trust which 'owns and operates Ngāi Tahu Holdings Corporation Ltd and its subsidiary companies and related trusts'. This is done through an equity arrangement where group profits are turned into $1 shares owned by the Charitable Trust (I think).

But there is only one trustee of the Charitable Trust and that is the tribal council, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

As an ex-chief executive of a UK charity this looks a bit odd to me because there are no independent, non-paid trustees of the Charitable Trust to ensure that it fulfils its charitable objects. In effect the body that governs the charitable trust is the Board of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu made of of the 18 paid and elected Representatives and the Chief Executive. .

It is interesting that an act of parliament was required to establish Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (sometimes referred to as TRONT). This seems to have been largely due to the fact that an Act was needed to dissolve the Ngaitahu Maori Board.

Other than dissolving this corpoate body (and another, the Te Runanganui o Tahu Incorporated) the main purpose of the establishment of TRONT was

to assume responsibility for the protection of the beneficial interests of all members of Ngai Tahu, being beneficial interests represented in the Papatipu Runanga of those members or in terms of the individual beneficial rights of those members (Act Preamble).

The Act also established the membership of the Ngai Tahu through kinship to Ngai Tahu tribespeople recorded in the 1848 census. A roll of all eligible members was to be drawn up under a provision of the Act. There is a slight confusion here becasue the members of TRONT are not the same as the members of Ngai Tahu. The former are the 18 regional councils (Papatipu Runanga) of the tribe while the latter are individual adults. But both are referred to in the Act as 'members'.

Rather confusingly, for me at least. membership of a regional body is not decided by georgraphical location but by descent. The Act (13/1) says

Each member of Ngai Tahu Whanui is entitled to be a member of each Papatipu Runanga of Ngai Tahu Whanui to which he or she can establish entitlement by descent.

This seems to assume that people establishing descent from the 1848 census will be in the same geographical area as their forebears. One would assume given the Maori move to the cities in the post-war period that this was often not the case.

In effect the Papatipu Runanga structure was a fudge that was in part supposed to resolve the difficult question of the distinction between an iwi - a tribal grouping - and its constituent locality-based sub-tribes - hapu - formed of a network of extended family groups (whanau).

Hapu often acted as independent bodies from the iwi to which they gave their loyalty and in case conducted the land sales the underlay many of the grievances brought to the Waitangi Tribunal - this was the case with the sale of Westland by the Ngai Tahu hapu - Poutini Ngai Tahu (see The Arahura Deed).

Also somewhat confusingly the Act seems to allow for an indivdual to belong to more than one regional body - which given that this confers voting rights is a democratic anomaly.

This is the case - see this letter of complaint from Richard Parata in 2009 to one runanga on the conduct of elections for their TRONT representative posted on the discontinued 'oppsotional' blog Ngai Tahu Shareholders.

The Act also ratified a charter (in effect a constitution and set of rules) agreed by representatives of the Papatipu Runanga in 1993 and specified that the Charter needed to set out the manner of the appointment of regional representatives to the tribal council. In 16c it introduced the rather strange manner of this election -namely a postal ballot by all constituents of a regional body to elect members of that body to appoint a regional representative to TRONT.

This strange two step process of appointment baffles me - why not have a direct postal ballot of the regional representative? Does this have something to do with a member of the tribe being able to claim descent to morethan one regional sub-tribe?

The Act stipulates that the Charter and any amendments made to it are available for 'purchase at a reasonable price' (18). As far as I can see this is not the case.

The Charter is available online but signposting to it from the publication page of the website is not as clear as it should be (in my view) given the centrality of this document to the council's governance.

The links you need to follow are either 'Te runanga Policy' or 'Legislation' which takes you to a page called 'Constitution and Legislation'.

The Charter is the third item of four on this page and no indication is made of the importance of this document that is indeed the legal constitution of the tribal council.

Instead above it the site refers the 'reader' to find the constitution 'of any company within the Te Rūnanga Group' to the NZ government's Companies Office, where under the entry for Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu there is no constitution listed.

The website at Publications says,

'The simplest way to keep up-to-date is to regularly visit the home page of our website.'

This assumes that (a) all 50,000 constituents of the tribe have internet access and (b) that they are internet-literate.

I'm not a lawyer but this to me looks like a breach of the spirit of the Act unless the Charter is available from the Head Office as a printed publication. No mention of this facility is made on the website as far as I can see.

Again, strangely to my eyes, amendments can only be made after 28 days notice for the meeting of decision unless (17c)

before the meeting proceeds to business, all the members of Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu agree in writing that the meeting is, notwithstanding the shorter period of notice, deemed to be properly convened.

This in effect would make it theoretically possible, with compliant Representatives, to make and agree proposals to the Charter on the same day.

You wonder why this sub-clause was included and why there is no specification of quorums and levels of majority voting for charter amendments - which is a usual check and balance in charitable organisations and democratic institutions.

With regard to the above it is unclear who the 'members' referred to in 17c are.

Section 9 of the Act states: 'The members of Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu shall be each of the Papatipu Runanga of Ngai Tahu Whanui' - that is the members are the regional bodies.

This is different from the Members of Ngai Tahu Whanui (Section 7) who are the adult constituents of the tribe by descent.

So when clause 17c above says that 'all the members of Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu agree in writing that the meeting is, notwithstanding the shorter period of notice, deemed to be properly convened' it is unclear who can give the signature for a tribal regional body that consents to the waiving of the 28 day notice rule.

The implication would be that it is the representative of the regional body who has been appointed to the governing body of TRONT but it is not clear.

The drafting of the legislation is a bit of a botched job in my view.

I thought I would have a look at the constitution of Te Rūnanga o Ngai Tahu. This is not directly available on the tribal council website. Instead it directs you to the New Zealand Companies Office portal. So there you search by Te Rūnanga o Ngai Tahu. This brings up basic information and says that the company has two directors - Arihia Bennett - the CEO and Mark Solomon - the Kaiwhakahaere/chair.

There are many documents listed here but no constitution.

Going back to the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu website I looked at the 2012 Charter of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu . At page 32 it says that one of the roles of the Office of Te Rūnanga is

to assist Te Rūnanga to use Charitable Trust assets prudently in its role as Trustee of the Charitable Trust, by pursuing in an efficient manner such Social and Cultural Development and Natural Environment objectives as may from time to time be approved by Te Rūnanga, in so far as such Social and Cultural Development and Natural Environment objectives so approved fall within the charitable objects of the Charitable Trust.

(Note: footnote 82 is missing here - instead footnotes 79, 68, 69 and 70, are wrongly at the bottom of p.32.)

On the next page (p,33) under Methods of Control the Charter states that,

'Te Rūnanga as Trustee of the Charitable Trust will appoint and remove directors and the chair of the NGHC [the Holding Corporation] Board.

What the Charter does not appear to say is who or what appoints the Directors - of which there are just two (the Chair of the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu's Board - Ta Mark Solomon and its CEO - Arihia Bennett) - of the registered company, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, which in turn is the sole trustee of the charitable trust.

Normally this might be done at the Annual General Meeting but not here and whereas point 27 on p.54 says a CEO shall be appointed there is no mention that the CEO will also be a director of the company, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (p.54).

There is also no limit on the number of times a Representative of one of the Members (the regional Ngai Tahu Papatipu Runanga) can stand for Chair or Vice chair nor is there an automatic limit on the number of years they are appointed (see 6.14 p.20).

At point 7 (p.21) there is real confusion about the definition of 'members'. In the Interpretation 'Members' are defined as 'the eighteen Papatipu Rūnanga' - that is the regional Runanga (councils/entities - this key word is not defined). But elsewhere in the Interpretation there is another meaning of members - as in “member of Ngāi Tahu Whānui” (broadly speaking) someone descended from someone in the 1884 Blue Book.

At Point 7 a new meaning of member is introduced - namely 'the members of each Papatipu Rūnanga'. It sounds like this menas the 'members of Ngāi Tahu Whānui of each Papatipu Rūnanga' but it is not clear.

Anyway, its says that the members of each Papatipu will elect every three years (unless the number of candidates does not exceed the number of vacancies) three Appointment Committee Representatives to their Papatipu who are responsible for appointing the Runanga Representative to the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu's Board.

This again puts no time limit on the appointments of Representatives to the Board of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu because elections on a three yearly cycle only need to be held when candidates exceed vacancies.

At point 8.4 (p.26) the Charter states that Representatives (ie Board Members) may be paid - 'prescribed remuneration' - by the entity 'Te Runanga' which means, the Interpretation tells us, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

This seems to mean therfore, that the Represntatives as the Board of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu can, more or less, prescribe their own remuneration.

It seems to me there is an awful lot of circularity and that there are very few checks and balances in the Charter with regard to the governance of the all-powerful tribal council and company Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

And nowhere does its state how or by whom the Directors of the company, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, are to be appointed. In fact, as far as I can see, the Charter is unaware that there are directors of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu as named on the documents at the Companies Office .

The reason I am banging about all this is because when a company is set up to serve the interests of a broad community (particularly one that has suffered great disadvantage) the way in which its governace is structured is very important.

If there are not sufficient checks and balances on the setting of things such as pay and rewards and strategic objectives that are congruent with charitable aims there is ample room for for, to put it bluntly, abuse by design or, probably more commonly, abuse by neglect.

In the UK in my experience of the charities world such checks and balances are achieved by having:

- trustees who are independent and not remunerated;

- fixed term and number of term limits on such posts as Chair and Board Members;

- a Company Secretary who has a legal duty to ensure that the Company acts within its founding documents (Constitution/Charter/Charitable Objects).

Direct elections of Board members by their constituency is hard to acheive due to problems with participation and the often personal relations (and not always happy ones) in tight communities.

But in my opinion having direct elections to appoint three people who then appoint the community's Board representative is unlikely to resolve this difficulty and makes the process again open to abuse by neglect.

Since it inception the company has done very well to increase its assets which now stand at just over NZ$1bn - although net assets are less at $877.3m.

The growth of the company's assets has been generated through

- the investment of the 'Trust Funds in Perpetuity which is comprised of although funds received from the original Crown Settlement, and subsequent Fisheries, Aquaculture and Relativity Settlements and totals $294.6m.

- the retention of earnings (ie they have not been distributed) of $391.4m

- the assets that come under the heading of 'Asset Revaluation Reserve – Available for Sale' of $182.6m which includes the fair market assessment of the company's large holdings of Ryman Healthcare shares of $191.1m.

Taxation

This is interesting. On a revenue of $230.3m the company paid just $162,000 (thousands) of tax.

The taxation regime is explained in the notes to the accounts in the 2013 Annual Report. This states that

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu is taxed on its business income at the Māori Authority rate.

However,nearly all of the company activities are not taxed because,

With the exception of Seafood’s Australian subsidiary, the Ngāi Tahu Charitable Trust and its subsidiaries have charitable status for Income Tax purposes.

The current NZ rate of corporate tax is 28% on net profits.

Expenses and Remuneration

In the Notes to the Financial Statements there is no breakdown of the large item, Operating Expenses - Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu of $11.4m.

It is unclear if this expense is just for the tribal council company or if it is for the whole group. At first it would appear to be be for the whole group in as much as the revenue figure of $230.3m appears to be a gross rather than net figure (although this is not specfied).

But the Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu operating cost of $11.4m is less than the wage bill under note 13. KEY MANAGEMENT PERSONNEL COMPENSATION.

I calculate the remuneration bill for the company for its key management personnel - directors, represetatives and 81 key management staff (all paid above $100,000 per annum) is in the order of $17.3m. However, this figure does not appear in the accounts and suggests that the revenue figure for the group is a net figure. To me this is mysterious.

What is fairly clear from this is that the tribal distribution from Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu of $19.9m is not much bigger than the bill for remuneration to 'key management personnel' of $17.3m (which presumably does not include national insurance and company pensions contribution).

Indeed, if you take the distribution figures on page 6 of the report of $17.3m it is exactly the same (give or take the midpoint averaging I have used in my spreadhseet calculation).

In fact it is almost uncanny: the dsitribution figure is $17.303m and my calculation of key management personnel remuneration is $17.323m. I hope this is just a coincidence and this remuneration cost is not being used to set the level of distributions.

Nowhere in the Final Report 2013 are we told how many people Te Runanga o Ngfai Tahu (TRONT) employs, which again seems strange to me. Surely showing how much employment you are generating is a good thing for a social development charity to do, no?

To find out this you have to go to the New Zealand Charities Commission website and search for Ngai Tahu Charitable Trust and then click on the Annual Return Summary 2013 button. And hey presto we get a new set of figures.

Here we find that the number of paid people in an average week employed by the NTCT is 273 full time and 28 part time and a heading for Salaries and Wages under Expenditure is $26,154,83.

We also find here that NGCT's total gross income is $269m whereas the 2013 Annual Report gives a Revenue & Other Income from Trading Operations figure for year ended June 2013 of $230.3m.

Maybe there are different reporting periods? But no, the Charity Commission figures are also for year ended 30 June 2013. Hmm. There's a big difference between these two figures of $38.7m. I've no idea why.

I've provided a screenshot of the Income and Expenditure as reported tothe Charity Commission below.

More surprises are in store. For example, the Cost of service provision (excluding salaries and wages) is NOTHING. How can that be? TRONT is not a trading company and its Operating Costs in the Annual Report are reported as $11.4m.

Are we seriously to believe that all that Operating Cost is for salaries and wages and there are no costs for such mundane things as offices and computers and stationairy and publicity etc.?

My suspicion would be that all these costs have been put in the 'Costs of trading operations excluding salaries and wages' below it of $156.4m or into the catch-all figure for All Other Expenditure of $15.7m.

Continuing with my exploration of the NTCT page on the Charity Commission website I noticed that the NTCT 'is a member of the group called Ngai Tahu Charitable Group'. This took me to a page called The Group Summary which lists 41 Group Members.

Ignoring this for a moment I clicked on the Annual Return 2013 button only to find that the Financial data in this is exactly the same (at least to my eye) as that filed in the NTCT 2013 Annual Return 2013. Hmmm.

Then I clicked on the first of the 41 Group Members, Ngai Tahu Communnications Ltd thinking this might give a break down of of some of those elusive costs.

But lo and behold when you click on the Annual Return 2013 button called 'Consolidated Annual Return' what do we find but the exact same financial data as provided in the Charitable Group and Charitable Trust pages of the Charity Commission website. It's just been repeated. Just to check I clicked on a few of the other Group Members and you guessed it, it's the same figures copied across to each member (well, at least it looked like but I didn't check them all).

Now this is pretty weird. I can understand presenting Consolidated data for really samll fry Group Members but even for Ngai Tahu Property which is the daddy of the Group Members by size and activity (it accounts for 43% of the Group's Assets p.5 2013 Annual Report) we just get the Consolidated Annual Return. (According to the NZ Herald NT Property 'is the South Island's biggest property company').

To my naive eyes this makes a mockery of charitable reporting.

In the first place what is the point of simply reproducing 41 times the same financial data. It tells us absolutley nothing.

In the second place the activities of Ngai Tahu Property may contribute by transfers of operating surplus via the NT Holding Corp to the Ngai Tahu Charitable Trust but how can its entirely commercial activities be defined as 'charitable' with all the tax exemptions that gives rise to?

This confusion is nicely exemplified when we click on the Charity Rules (17.03.2008) button of the Ngai Tahu Property page of the Charity Commission website.

This takes us to a 37 page set of rules. The first page is entitled Constituion of Ngai Tahu Property Limited and the third page is entitled Constituion of Ngai Tahu Property Trust.

The ammended rules of September 2009 rectify this and Ngai Tahu Property Limited is used more consistently.

If NT Property was only building below-market-rent social housing I can see how that could be defined as 'charitable' but otherwise it seems to me that New Zealand charity law is in a bit of a mess.

I know and appreciate that the whole Ngai Tahu enterprise edifice is at least officially about restitution and that there are strong arguements that the growing returns from the original and the pitiful $170m from the Crown should not be subject to the same tax as truly commercial activities. But this is not my real concern.

My real and abiding concern with all this mess is that there is precious little transparency and few checks and balances (except goodwill and conscience which can of course go a long way but can also fall a long way short) into the working of the NTCT, TRONT and the NG Holding Corporation.

Don't get me wrong, I'm not saying there is anything to hide. Although there are issues that I would want to look at further if this charity were working in my name - for example

- the cost to benefits ratio at TRONT,

- remuneration across TRONT and the Group,

- TRONT's charter and governance,

- and the balance between equity growth and social development distribution for the benefit of the 55,000 Ngai Tahu members.

No. Don't get me wrong. TRONT is an amazing and amazingly big social investment company. But to the outsider who starts nosing around it is really difficult to understand how it really works and how it really puts its massive resources to use for the benefit of the people for which it was established.

Audit Report in the Annual Report

The Audit Report in the Final Report 2013, which presents an 'unmodified audit opinion' by Deloitte only concerns the Summary Financial Statements presented in the report and not the audited group financial statements of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Ngāi Tahu Charitable Trust.

As such the Audit Report in the Final Report is a report on the consistency of the Summary Financial Statements with the full audited group financial statements of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Ngāi Tahu Charitable Trust.

I have been unable to find those full audited group financial statements of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Ngāi Tahu Charitable Trust and that is a problem.

I am not the only one raise questions about the presentation of the company's accounts (see here in the New Zealand Centre for Political Research - a free market/right wing thinktank - and a more detailed piece by Dr Michael Gousmett for the NZCPR) who is a specialist on the charitable sector. He concludes his section on the difficulty of making sense of the2012 Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu and Ngai Tahu Charitable Trust financial statements and accounts by saying,

Excesses in remuneration are not unique to the for-profit corporate sector, as such figures now show.

Gousmett does not justify his accusation of 'excesses in remuneration' and my point would be that from the way the rumeration data is presented it is very difficult to work out where this remuneration is being made - for example it cannot all be within the operating costs of Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu because the total remuneration listed is greater than its total operating costs - let alone whether it is a justifiable level of remuneration.

The fact that no mention is made of any kind of Remuneration Committee within Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu's Charter leaves me wondering how levels of remuneration in Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu and its subsidiaries are set and by whom.

(Many Representatives are Members of Remuneration Committee however - see 2013 Annual Report p40-41 and Ross Keenan is the Chair of it.)

So I have no great sympathy for the NZCPR but Gousmett also points to the difficulty of understanding statements in the Final Report of 2012.

This particular issue appears to be repeated in the 2013 Annual Report where in big bold text on page 15 the Ngai Tahu Holdings Corporation says it carried out,

'Distributions' to Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu [of] $28.2m'.

On the face of it this suggests that $28.2m went to Tribal, Rūnanga and Whānau distributions.

But we have already been told, again in big bold letters on p.6 that,

Tribal, Rūnanga and Whānau Distributions(up $2.1m from 2012) [were] $17.3m.

It is possible to get close to the $28.2m figure from the Summary Accounts but it requires a lot of rooting around and some maths.

To do this you have to go to p.26 and the Summary Group Statement of Comprehensive Income.

(In passing I find it absolutely bizarre that there is not a matching Summary Group Statement of Comprehensive Expenditure which is absolutely normal in charitable summary accounts and would make it much easier to compare income and expenditue).

Anyway going to p.26 we see that in the Comprehensive Income Table under 'Tribal Activites' there are two large negative items

- Operating Expenses - Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu of $11.416m and

- Tribal, Rūnanga and Whānau Distribution Expenses of $19.887m.

Again in passing it is amazing to me that there is nowhere in the Final Report a breakdown of the large expediture accounted for by the heading Operating Expenses - Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu. This is impportant for transparency and also because, again on the face of it, it looks like Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu's costs of $11.4m are very high compared to its distributions of $17.3m.

Any reader might ask quite reasonably why is the Tribal, Rūnanga and Whānau Distribution Expenses of $19.887m in the Summary Financial Tables not the same as that reported on page 6 of $17.3m?

As far as I can see this is because a heading in the Income table called Revenue relating to Tribal, Rūnanga and Whānau Distributions (that is not explained) of $2.584m needs to be subtracted from the $19.887m figure. This then gives a total of $17.303m.

Again and to the side it was interesting how the Holding Corp transfer to TRONT was covered in the press. In the NZ Herald of 2 Oct 2013 we got this below which glides sweetly over the TRONT operating cost:

Ngai Tahu's holding company, which owns its commercial assets, paid $28.2 million to the iwi, up $2 million on last year. That would be used to fund development programmes in health, language, education and a superannuation scheme, Whai Rawa, Burt said. Whai Rawa had a membership of over 18,000, he said.

Charitable and company Financial Statements are never easy to read but these ones in their summary form are almost incomprehensible. Looking at the company's 2025 Vision Statement on the section under Governance there does not seem to be any plan to change this.

The Gousmett comments were covered by the NZ Herald of 29 June 2013. I nthis article Gousmett also said that the amount paid out to runanga compared to the iwi's total wealth appears minimal.

I have to say I find this situation shocking.

When you combine

- the lack of checks and balances in the company's Charter (see above),

- the two unexplained directorships of Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu held by the chair and CEO,

- the confusion and opaqueness of the Summary Financial Statements and

- the lack of accounting for the expenditure (costs) of Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu of $11.4m compared to development distributions (benefits) of $17.3

we arrive at a situation where it is very difficult if not impossible for an outsider or member of Ngai Tahu to hold this very large community-interest company and charity to account.

More on remuneration - disquiet over 'huge' pay increases for chair, deputy and their asistant in Feb 2009 (NZ Herald).

Interestingly Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu replied to a Ministry of Economic Development proposal to introduce standards for auditing and assurance for larger registered charities in 2012.

Whilst supporting the proposal for standards the company, through its Group General Counsel, Chris Ford, recommended that,

If an entity is audited as part of a wider group audit that this will be an acceptable means of assurance for the relevant entity.

In other words the company did not want audits carried at the level of subsidiaries or members - such as the 18 Runanga Papatipu that constitute the iwi's geographical bodies.

This was largely due to considerations of cost.

The NgāiTahu Charitable Trust (the Trust) has a large number of associated charitable entities (see Appendix One). The Trust has thorough audit processes which match or exceed those of publicly listed entities. Any requirement to separately audit each entity associated with the Trust would add a substantial burden to the group and not add any additional transparency or reliability to the financial reports produced.

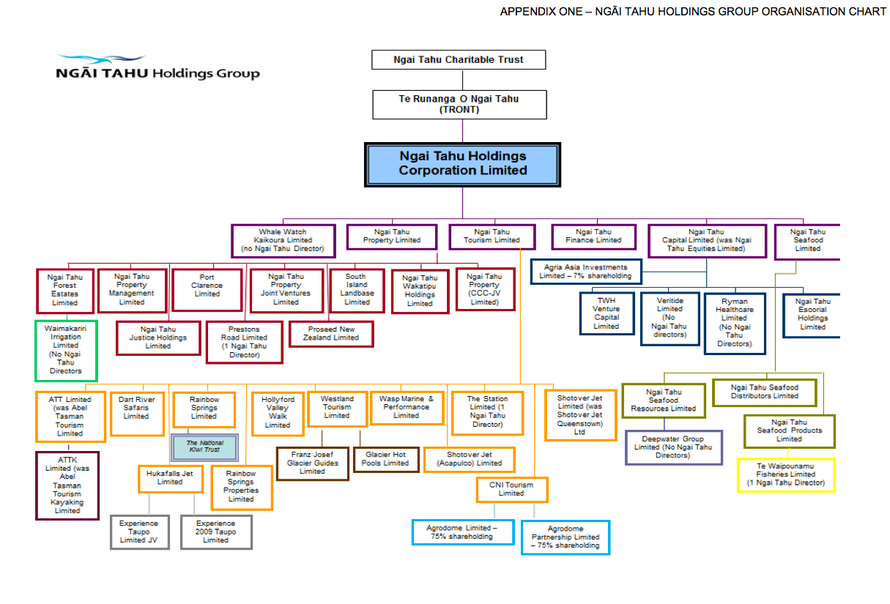

Appendix One is reproduced below.

This chart in itself is interesting because it promotes Whale Watch Kairoura to the status of a Holding Corp subsidiary whereas in the Annual Report 2013 it does not appear to be one - in that it does not have a separate report. The same can be said for Ngfai Tahu Finance.

The chart also does not show the 18 Papatipu Runanga which the text of the submission says are each 'currently required to complete an annual group audit'.

Given that Ngai Tahu Holdings Corp has assets of $877m it does not seem unreasonable that each of its subsidiaries should be subject to external audit. The same goes for the Holding Corporation and Te runanga Ngai Tahu and the Charitable Trust.

From the information presented it is difficult to form a judgement on the individual Papatipu Runanga because although the text says that each of them is 'made up of a number of entities, both charitable and non-charitable' the scale and arrangment of these activities is not shown on the chart. However, the fact that charitable and non-charitable entities operate within the Papatipu Runanga would ring alarm bells in many charity circles.

The recommendation that if an entity is audited as part of a wider group audit that this will be an acceptable means of assurance for the relevant entity makes little sense becausse it does not define what the 'group' is.

This could be taken to mean that audit at Te runanga Ngai Tahu should only take place at the level of the Charitable Trust, or Te runanga Ngai Tahu or the Holding Corp, or its subsidiaries.

My concerns notwithstanding the Holding Corp was recently praised by the Wall Street Journal for its acquisition and sale of Ryman Healthcare shares.