Golden Bay VI: The Karst Country of the Cowin Road

I thought this little strip of coast so far from 'anywhere' was one of the most amazing places in New Zealand. Of course the weather helped and we were probably there for less than an hour.

The land along the coastal strip south to Kahurangi Point was cleared by hand before the advent of bulldozers and JCBs. It was done in large part by three generations of the Richards family who settled at Paturau.

"They had very little money. They would buy a couple of hundred acres, clear and grass it, then buy some more. Initially they bought some poor quality calves but once they had bought two or three blocks, they were on their way. From the 1920s to 1940s, about six men were employed to clear the bush. They used axes and saws and then stacked up the trees and burnt them. They would fell 100 foot rimu trees and set a fire at one end which would burn for a week leaving a long streak of ash which fertilised the ground."

Farm work was supplemented with work in the local coal mine to bring in a bit of cash.

Between 1910 and the 1960s the Richards would take cattle to the Annesbrook abattoir from Paturau on a seven-day drove.

"We'd bring the cattle up from Rata Creek to Paturau and then time it so we had a full moon for the tides. We'd leave at moonlight, walk along the mudflats at Westhaven [Whanganui Inlet] and through the Pakawau bush. That was a long day but the first part of the trip was more leisurely because we owned land at Ferntown and Takaka. We'd rent paddocks for the night for the rest of the drove."

(See The Prow: Paturau)

Each bend of the road seemed to offer something new. Here the scour of the wind and a reminder of a bad blow in the short days of winter, with fantasies of driving back through the dark, lights picking out the uncertain edge of the road in the lashing rain, the ground sodden and threatening to slip and slide away into the sea.

I was reminded of parts of the Isle of Skye in the Western Isles of Scotland - a long single track road that leads to somewhere that feels a place apart and yet has its own integrity, that feels like a community carved out and cemented by the struggle with land and weather, secure of its own precarious place in the world.

Here on this far north-west corner of the South Island you get a really intense sense of being on an island - the Tasman Sea to the west stretching over 1000 miles to Australia. To the east the limestone bluffs and behind them mile upon mile of uninhabited, rugged, forested hills that rise up to the heights of the Wakamarama Range and Mt Stevens at 1 213 metres.

Its a 10km tramp through pathless, roadless, arduous and lumpy country to the rich dairy farms of the Aorere River valley. From the end of the Cowin Road and the lighthouse at Kahurangi Point there are 40 kilometres of untouched, unpeopled coast to the Karamea-Kohaihai gravel road that comes up from Westport.

The Karst Country

The Kahurangi National Park is one of the most geologically complex areas of New Zealand. On the far west of the park are granites variously overlain by limestones, marbles, conglomerates, siltstone and coal measures (Kahurungi National Park Management Plan p.17).

The high peaks and areas like the Gouland Downs are made up of eroded and incised peneplains ('a low-relief plain representing the final stage of fluvial erosion during times of extended tectonic stability,' Wikipedia).

The Takaka and associated Paturau Limestones were laid down when most of nascent New Zealand was submerged beneath warm seas 55-25 MYA - in the Late Cretaceous/Cenozoic era. (Richards 2003 p.19)

The Takaka Limestones were metamorphised by granite intrusions and tectonic pressure into the so-called 'Arthur Marble 2' (after nearby Mt Arthur) which is a Late Ordovician black limestone and calcareous mudstone.

Marble from the Kairuru Quarry (1911 - 1912) was mined and transported to Wellington for use in building parliament (Richards 2003 p.38).

The most spectacular and accessible karst country is inland from Karamea (50-60km south of Paturau) - but only accessible from the Buller valley and Westport much further south still. Here there are huge cave systems and the spectacular Oparara limestone arch.

(Source: This and subsequent sections of this page draw heavily on the MA Thesis in Environmental Science of Danette Richards, Geomorphological and Environmental Studies of Karst, Northwest Nelson, New Zealand - University of Canterbury, NZ: 2003 - and is referred to above and below as 'Richards 2003').

Little mention is made anywhere on the internet of the Cowin Road and the Paturau limestones. It appears remarkably and brilliantly overlooked but for a few cavers. It is briefly acknowledged as one of the three areas of karst landscape in New Zealand - see below.

This scant regard for the Paturau karst landscape is due to its remoteness and exclusion the Kahurangi National Park and the Northwest Nelson Forest Park. It also has little economic significance in that its aquifers are not important for centres of population and farming - like Takaka and Motueka (the latter with its intensive apple, hop and tobacco industries) - and its landscape is not on the main tourist trail.

After all, the Paturau is hidden away at the end of a 25km gravel road that winds through forest, crosses numerous inlets and the swamps of Mangarakau never passing a house let alone a cafe or shop. It is wild, isolated country and yet it feels remarkably homely.

'Karst topography is a landscape formed from the dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum. It is characterised by underground drainage systems with sinkholes, dolines, and caves.'

The etymology of 'karst' is complicated,

According to the prevalent interpretation, the term is derived from the German name for the Kras region (Italian: Carso), a limestone plateau surrounding the city of Trieste in [north-eastern Italy] (Wikipedia: Karst).

Karst landscapes are formed when rainfall picks up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and the soil (where there is 100 times more carbon dioxide than in the atmosphere).

This mixture forms carbonic acid which erodes limestone. Erosion is fastest near the overlying soil layer where the acid is strongest. Ninety per cent of dissolution takes place in the top 10 metres of limestone. The amount of rainfall and the purity of the limestone both affect the rate of erosion.

Karst systems have an amazing intimacy. They are like rock-gardens before rock gardens were invented - think of the limestone pavements of Malham Cove in the Yorkshire Dales in the UK or the Burren on the north west coast of Ireland.

They are landscapes within landscapes and have something of Chinese ink brush paintings of mountains and gorges. And they are like 'land art' before the fumbling hand of humans intervened.

They are full of mystery and indeed terror. The beautiful zen-like quality of the surface hides great sinkholes (see picture of the the 183m deep Harwood's Hole near Takaka at end of this page), swallowed streams, cave systems - drowned and not - of immense complexity and full of the darkness and pinchpoints of nightmares.

I remember watching with horrified fascination as a group of divers geared-up in cumbersome suits, a rope holding them together, to enter the freezing waters of a south-west French gouffre - resurgence - to disappear into the eternal underwater dark, beneath the huge weight of rock pressing down from above, their last air bubbles breaking the surface of a pulsing pool hidden in deep forest.

Limestone derived soils are fertile but fragile. The soils formed from them 'are the residues remaining after solution processes have removed the balance of the rock' (Richards 2003 p.31).

Soils derived entirely from carbonate residues are known as 'rendzinas'. They are fertile but lacking in phosphate and normally lie directly on bedrock with no subsoil. They resistance to erosion comes from their high fertility, organic content and good structure. The lack of surface water and potential for drought are serious limitations to intensive farming.

Karst soils develop very slowly because solution takes away most of the weathering residues. The thin veneer of soils is prone to degradation and erosion or loss simply by being swallowed or washed down surface openings like dolines and fractures.

Rainfall on the Cowin Road is in the region of 2.25 - 2.50 metres (98.5 inches) a year (that's about double the rainfall of Glasgow in the UK).

Harry and Laurence Richards of Paturau Farm were early advocates of post-war aerial phosphate top dressing. Says Harry,

"There was a high price for wool at the time so farmers had a bit of extra money. We bought some fertilizer for a property at Kaihoka [on the north side of Whanganui Inlet] we were developing and thought the plane would be able to land on the beach but it couldn't. It took us a year to construct an airstrip and in the meantime the sacks of phosphate had become like concrete."

Better roads were driven through in 1962 , more landing strips have been laid down and since then 'tonnes of super phosphate, lime and potash have been spread, boosting the productivity of the farm'.

The carbonate rocks of the Arthur Marble in north west Nelson host New Zealand's most notable karst landscapes.

These include New Zealand's largest spring (Te Waikoropupu Springs), the deepest, longest, and possibly oldest caves such as Nettlebed (889m deep, 25km long, and over 700,000 years old), and the largest subterranean rivers in the country.

The karsts of the Takaka region are renowned for the 176m free-fall shaft of Harwoods Hole, the scenic Marble Plateau Karst, the resurgence or source of the Riwaka River and the numerous and extensive cave systems such as Greenlink (approximately 360m deep), Middle Earth, and Perseverance (Richards 2003 p.8).

Interestingly, Maori settlement on karst areas was limited because of the rahui (embargo) emplaced on karst areas by local iwi. In Maori mythology Karst, with other landscapes, represents Papatuanuku (the Earth Mother) and the karst topography and, in particular, caves are thought to be where the world and universe come together. It is believed that karst landscapes were associated with the presence of a spiritual entity or taipo (or goblin) which was said to reside in the Canaan area between Takaka and Motueka (see Richards 2003 p.37).

The terminolgy of karst features is drawn from German.

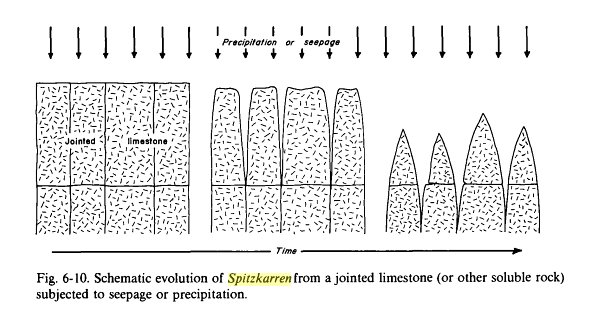

The 'karrens' - forms of surface erosion of limestone pavements and blocks - run into a bewildering array of forms and sub-forms (first, second and third order). They are supplemented by 'cockling', 'flutes and scallops', and 'dirt polygons and rims'. At times the language at times gets so 'axially ablated' that it appears to lose all meaning (see example below).

There is a nice collection of photos of different karstitic forms here .

But these things are clearly important. With regard to the spitzkarren it seems that the classic form of this is a vertical piece of limestone with a sharp edge or projectile 'nose cone'. And the sharper the cone the more indication that the karren was formed in an unmantled manner, so to speak. That is, it was not covered with soil or debris. Karren formed beneath the soil have a more rounded and smooth shape (see Sedimentary structures, their character and physical basis, Volume 2 p.229).

Without more guidance it is hard to know how the distinctive limestone forms of the Cowin Road were formed. It would seem from the lack of sharp edges and projectile shapes that there were formed with a soil covering. This was in all likelihood a soil covering supporting thick lowland forest.

You wonder how quickly these forms came to the surface with the removal of the forest cover in the 20th century. Were they revealed as the trees came down or have they been revealed subsequently by erosion and sheep and cattle grazing?

This latter seems unlikely as limestone soils are generally thin. Maybe these forms have been here for thousands upon thousands of years hidden by forest. The ample rainfall of the coast gradually dissolving out the limestone with atmospheric and soil-based carbon dioxide.

It is unlikely that they have been affected by glacial karst processes as little of the north of the South Island was under ice in the Ice Ages. It is also unlikely that the hillside karst features were affected by sea level changes. If anything glacial rebound in the Southern Alps might be pushing the northern coasts of the South Island downwards.

So other than 'aggressive dissolutional processes' working over millenia we have few other clues as to how the karst columns and outliers of the Cowin Road/Paturau River were revealed.

Looking back through my photos there are clearly different bands of mudstone and limestone at Paturau/Cowin Road. The bluffs above the river show wind erosion of close bedding plains - somewhat like the erosion as Punakaiki (Pancake rocks).

Perhaps it is the exposed position of these rocks that has led this to become so pronounced but it is interesting that karst columns and outliers further south down the Cowin Road do not show bedding plain erosion. This would suggest that either these are much less exposed to the prevailing westerlies and their sand/grit/brine load or that they are made of tougher - more marbelized - limestone.

Delving further into this it seems that the Takaka Limestones - of which Paturau is a part - were laid down between 22 and 13 MYA through marine sedimentation processes that differed over time depending on sea depth, currents and climate.

Sedimentation started with glauconitic calcarenite and calcareous conglomerates and progressed in the middle measures (of the total beds that vary from 5 to 100m in thickness) to bivalve-briozoan-barnacle-foraminiferal-algal calcarenites which in turn were completely dominated by briozoan calcarenites of the mid-outer shelf depths (See Kamp, P. and Neslon C. Nature and Occurrence of Modern and Neogene active margin limestones in New Zealand NZJGG 1988 Vol 31, N.1 p.11).

What this seems to suggest is that the Takaka limestones are made up of three distinct beds that shift from rough conglomerates to shell-built limestones to limestones formed from briozoa (tiny sea organisms less than 0.5mm long). The bottom bed is the least pure form of limestone whilst the topmost and most recent is the purest being 95-98% Calcium carbonate (ibid p.11)

Once laid down the limestone was then overlaid by a sudden Miocene 'influx of hemipelgaic mud and distal turbidites' - that is, non-calcareous deposits that formed mud- and sandstones.

These differences are accounted for by the 'transgressive-regressive cycle' which in effect means that sea levels rose and fell and as the water depth and proximity to land-based deposition by river varied different forms of calcium, mud, sand, and gravels deposits were laid down.

So in effect within the Takaka beds there is a profile from the bottom up of increasingly pure forms of limestone covered by a cap of mudstone. In many places these beds have disappeared completely through erosion. But in others they remain in various stages of erosion.

These various limestones and mudstones were then subjected to metamorphic pressures - the sheer weight of accumulation, horizontal compression through tectonic forces and heating through granite intrusions from below.

At Paturau/Cowin Road the limestone/marble beds are overlain by what looks like a flaky mudstone.

The position of the bluff edge has presumably been in part determined by faulting in the area - although this is more intense in the Takaka area than the Paturau River - for example - the escarpment of Takaka Hill is formed along a major faultline - the Pikikiruna Fault.

Takaka Hill is nearer to Marlborough Sound to the east which is formed from the continuation (transfrom basin) of the great Alpine Fault that results from the collision of the Pacific and Australian plates.

The Takaka Hill Fault and the fault that helped form the bluff line at Paturau and Mangakarau run almost exactly parallel.

The most distinct karst formations develop in the purest and hardest limestone - that is, in this case of the Takaka sequence in the top-most beds below the mudstone cap.

This would perhaps explain why the karst columns and outliers are relatively high up the slopes of the bluff.

The different hardness and purity of the limestone beds is particularly evident along the perpendicular bluff cut by the Paturau River (which may follow a transverse fault).

Here there seems to be a harder layer of limestone beneath the forested shelf with a more dissolved layer beneath it and beneath that a more rubbly layer.

The undercutting action of the Paturau here leads to a particularly steep slope and it may be that karst outliers here once detached from the bed rock tumble into the river.

Richards (op cit pp8-9) relates that the Takaka Hill limestone was uplifted by 1km due to tectonic pressures and faulting on either side of it.

To the west of Takaka Hill the land has been uplifted further through mountain building associated with the colossal forces of the collision of the Pacific and Australian plates forming the Haupiri and Wakamarama Ranges.

Presumably the uplifted mudstone and limestone on this land has long been eroded away due to greater rainfall and limited glaciation at greater altitude with the exception of the dolomite outcrop on Mt Burnett.

At Paturau/Mangarakau it is possible that a further segment of limestone was uplifted to form the chain of bluffs that run from Cape Farewell towards Kahurangi Point.

At a lower altitude these have been subjected to less intense processes of erosion. At the edges of the bluff scarp the hard limestones have been revealed with the regression of the scarp edge and over a vast period of times the limestone has been etched away by carbonic acid.

To complete the process the scant but fertile soil formed fell away around the remnant limestone pillars and karren and these latter were eventually revealed by the removal of forest cover by 19th and 20th century clearance and agriculture.

Trying to unravel the story behind the formation of the spectacular Cowin Road/Paturau River karst country maybe somewhat undermines the romance of the place but for me at least it helps explain the way it is.

And it is both a salutary reminder of the immense periods of deep time required to make landforms and landscapes and their fragility when we start to muck them about without understanding where they came from.

We never did get down on to Paturau beech but I came across some lovely photos of the wave-sculpted forms (below) we missed.

We were merely birds of passage who had stumbled across this beautiful corner of the north west South Island. Time was pressing. The day was using up. We moved on back over the now tiresome bends and causeways of the 'Dry Road' back to Golden Bay.

The biggest area of karst landscape in the South Island lies to the east of Takaka on the heights of Takaka Hill. This faulted landscape holds many doline and the huge and terrifying Harwood Hole.

I insisted on stopping on our drive in from Nelson to take a few pictures of the marble plateau karst on top of Takaka Hill (see below).

You wonder where all the water goes from this large area with not a stream in sight. A day later we found out when we drove up to the Te Waikoropupu Springs. The story continues on the next page.