Golden Bay IX: Taupo Point and Abel Tasman

The walk from Takapou Bay to Taupo Head is neither long nor arduous. We had tried it two days earlier and the tides were wrong. We eventually walked it in the late afternoon of a glorious Golden Bay late summer day.

The sun beat down from its angled position in the westering sky and beat up from the calm crystal clear waters of Wainui Bay. By the end we were bedazzled with the light and beauty of it all. On the walk we saw two people, some birds, a crab, two sea-going kayaks pulled up on the beach beyond Taupo Head and now and then could hear the radio playing on the mussel boat working its ropes in the bay.

There is a much longer, multi-day walk - the Abel Tasman Coastal Track - of 52km. We had tried a bit of it on the 'wrong tide' day but it seemed a lot of slogging through bush to get to Whariwharangi Bay and Separation Point (see map above).

New Zealand Fur Seals were the main draw but we were more than compensated by our fabulous walk out to Wharariki Bay on the west coast opposite Farewell Spit way around on the far north west side of Golden Bay (see my page New Zealand Fur Seals).

The path starts at the car park at the end of the road in Takapou Bay beyond an alternativey-looking commune tucked into the low hills. Its the Tui Spritual and Educational Trust if you want to check them out.

The first section of the path runs along a remnant bit of marsh and the salt flats of Takapou Bay and the sand spit that separates the flats from Wainui Bay.

It is an amazingly sheltered area with forest-covered mountains to three sides. A beat-up looking yacht was moored in the placid sparkling water close to the shore. Birds sang and a Silvereye caught my eye.

There is a little information point housed in a mini-wharenui (meeting house) with beautifully painted patterning on the roof ends and fierce and startlingly red carvings on the roof post and wharenui-ends.

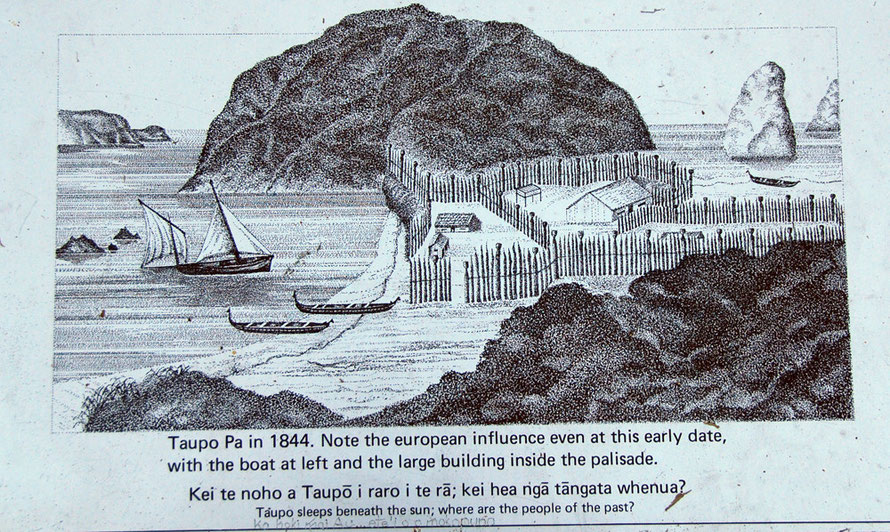

When we reached Taupo Point - which is a bowl-shaped headland attached by a thin neck to the mainland we came across a sign that told us that this had been the site of a Maori pa (pallisaded fort).

The sign on stainless steel showed an engraving (see above) of the two-chambered pa in 1844 with three canoes (waka) and a two-masted sailing boat. Underneath was written - 'Kei te noho a Taupo i raro i te r; kei hea nga tangata whenua?' and the translation 'Taupo sleeps benath the sun: where are the people of the past?'

Someone had added by scratching into the plate, 'Ko hoki mai au ....ete i o a mokopuna' which Google translate gives up as 'But for me .... Being of Children in' which might mean 'But for me ... being with child.'

There is something poignant about all this. All these Maori names and new-built reminders, here and at the Te Waikoropupu Springs - often reduced to the giggle-inducing 'Pu Pu Springs' - and on the western beaches outside of Auckland and the little signs we were to come across on the Otago Peninsula reminding us that someone had been here before the 1800s.

We had seen all sorts of people in Takaka, Pohara and Collingwood - crusty, bare-foot dreadlock boys and girls, artist types, and well-kept sleek and earnest Germans, even a bloke in his sixties decked out in full Leiderhosen.

We'd seen from afar sturdy, scowling farming types with knapsack sprayers in the midday sun and briefly met the cool farmer guy with pounamu and dreads on his quad bike with two sheepdogs out on the Cowin Road.

And we'd wafted through the local live music venue, the Mussel Inn, and through the lacklustre Takaka alternative market where I'd bought apples that looked like an English Russet.

And we'd mixed it with tourists and locals in the local supermarket, bought 'European bread' from German bakers and bantered about the price of John Bull boots with an Australian (who claimed they were half the price in Oz) in the Rural Service Centre Farm Store in Takaka.

I'd stood patiently with John to buy coffees in the Pohara coffee place and got a sense of the hip, laidback, middle-aged vibe as the woman cafe-owner bad-temperedly got on with making the coffee and her goatee-sporting, turntable-turning bloke explained how to get to the pathway head.

And I'd chatted away to the gardener - a refugee from Christchurch - at 'Chez-nous-briefly' (as we came to call our palatial beachside villa with its thousand bathrooms and impeccable objet owned by Singaporians).

But I could not recall seeing anyone who looked like a 'Maori', (which was obviously my idea of a 'Maori') the whole time we travelled around Golden Bay. Keri Hulme mentions (in The Stone People) that she worked in 'the tobacco' at Motueka over Takaka Hill.

I suppose the answer to the question - Where are the people of the past? - is that the people, tired of a marginalised and impoverished rural existence lived in parallel to the New Zealand pakeha community left the country and headed for the city in the post-II-world war period and through activism, militancy, parliamentary politics and a sheer refusal to give in galvanised that sense of 'tangata whenua' and through it created the Maori renaissance within and underneath and alongside the whole process of the Waitangi Tribunal.

But these were things I didn't understand at the time and only half understand now. But there was something disturbing about seeing a bunch a German school-kid hikers with all their multi-day trek gear waiting in the shade of the mini-wharenui for their lift to wherever they were going.

A brief history of Maori in Golden Bay says that, "Some of the place names and legends of Golden Bay are ancient, and derive from the Hawaikian Polynesian roots of the ancestral Maori. For example, the names 'Takaka' and 'Motueka' have probably persisted for centuries as place names in the district; Ta’a’a and Motue’a are a few miles apart on the island of Raiatea in the Tahitian group, believed to be the Hawaiki of several of the “Fleet Canoes” of the Maori migrations."

This note estimates that in the 1840s the Maori population of Golden Bay was 'up to several hundred people, with wide seasonal fluctuations ... [and that] over the decades following colonisation many left.'

It goes on to say that since then only a few Maori families have “kept warm the hearths of their ancestors’ papakainga” (traditional building/living land) in the Bay and that 'while retaining fierce pride in their Maori heritage, most Maori of the Bay share European ancestry and today stand tall in both cultures of New Zealand society.'

There is a local marae (meeting house) in Pohara, Onetahua Marae, that was established in 1986 in the old schoolhouse. It is the home marae for three local iwi: Ngati Rarua, Ngati Tama, and Te

Atiawa, but 'operates as a multicultural marae with the wider involvement of the whole community' (see Golden Bay: Maori History).

But that was then and we were soon tramping along the damp path by dense bush to regain the point where we have previously been beaten back by the tide two days earlier.

In fact, the tidal range in New Zealand is moderate with a maximum range of 4m in Nelson compared to say the 7m at Dover in the UK. Still, 4 metres of water is a lot taller than me.

On the half-run I snapped away at plants I sensed were important and that one day I would know something about. Little did I know just how much time I would need to identify them and begin to get some familiarity with the confusing endemic and indigenous biota of New Zealand.

Again that old familiarity/difference paradox was at play. I'd see pines and pasture that looked like 'home' - poplars and field thistles and marsh grasses and blackbirds and chaffinches - and then be confronted with things that I simply couldn't place in the framework of tacit knowledge of 'the living things around me' I'd picked up over 50 years.

Things like podocarps, weta, kauri, birds with wattles, and a bewildering array of ferns and hebes, griselinia and olearia, many with these confusing Maori names that didn't seem to be able to roll, judder or takaka off my tongue.

I wanted to compare the numbers of vascular plant species in the UK and New Zealand. Wikipedia: the Biodiversity of New Zealand says,

The biodiversity of New Zealand, a large island nation located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, is one of the most varied and unique on earth due to its long isolation from other continental landmasses.

And the New Zealand Plant Conservation Network says there are 2362 vascular - that is, flowering plants, conifers, ferns and club mosses - plants and that there may another 200 species yet to be identified.

One day I'll get the UK figures and add them in here.

First there was a plant that looked vaguely like a huge primrose, then a great tangle of something like a 'Russian vine' with a spider web woven (probably Pohuehue or Maidenhead Vine - Muehlenbeckia complexa) into its topknot, then amazing ferns and heart-shaped leaves with holes in them in deep shade.

This latter I regonised as the 'Maori toothpaste plant' (Kawakawa - Macropiper excelsum) pointed out to me by a volunteer a week and a half before of Tiritiri Matangi Island bird-reserve up near Auckland.

In fact Kawakawa had a multitude of uses in Maori medicine and was also waved as a welcome to guests and the leaves were used as a head wreath when mourning (Wikipedia: Macropiper Excelsum).

Then

- a familiar looking nightshade - the Small-flowered nightshade (Solanum nodiflorum)

- serried ranks of dense coastal hebes - probably Kokomuka/the shore hebe (hebe ellipitica).

- the climbing Fragrant Fern/Mokimoki (Phymatosorus scandens) pendulous on a tree trunk,

- Lemonwood (Pittosporum eugeniodes) with glossy leathery leaves and a vivid central stripe,

- a tree trunk with beautiful patterning,

- the feared New Zealand nettle tree/Ongaonga (Urtica ferox) that has actually been responsible for people dying

- the widespread poisonous bush (Tutu - (Coriaria arborea var. arborea) that grows widely

- the fiddlehead of a fern uncurling.

The Hebe plant group includes about 120 species (Gibbs, Ghosts of Gondwana, p.118) and is the largest plant genus in New Zealand. The New Zealand Plant Conservation Network (NZPCN) records 108 species of Hebe and Parahebe in New Zealand, 39 of which are at risk.

Hebes (from the Greek goddess of youth, Hebe) range from dwarf shrubs to small trees up to 7 metres high. They are found from coastal (large-leaved species) to alpine (small-leaved and scaled species) ecosystems.

A molecular phylogeny reveals that a hebe ancestor arrived in New Zealand in the Miocene period about 10 MYA. This was in the great mountain building stage when new habitats and microclimates were multiplying. In particular, the new alpine zone created opportunities for plant speciation - the creation of new species and sub-species - that were greater than ever before (Gibbs: Gondwana, p.118)

The Tutu is a very toxic plant in a country with few toxic plants. All parts produce tutin which can cause seizures, convulsions and death. It regularly kills sheeps and cattle and was responsible for the death of two circus elephants (See Te Ara).

It can also lead to the production of toxic honey. In 2008 nine people became seriously ill on the Coromandel Peninsula from eating toxic honey. The process whereby the honey bees pick up Tutu toxins goes like this: honey dew is excreted onto the leaves of Tutu by the tiny sap-sucking Passion Vine Hopper (Scolypopa australis). Bees then visit the Tutu flowers and pick up traces of the honey dew which gets incorporated into the honey (see NZPCN).