II. The Otago Gold Rush

The Central Otago Gold Rush of the 1860s was New Zealand's biggest gold strike and led to a rapid influx of foreign miners - many from the goldfieds of California and Australia.

The rush gave great impetus to the expansion of Dunedin which tripled in size in three years to become New Zealand's richest and largest city with disastrous sanitation, burgeoning crime, fine architecture, the first daily newspaper and 'the celebrated (and notorious) Vauxhall pleasure gardens' (Dunedin City Council).

The gold rush was short-lived with most of the smaller new settlements deserted within a few years while gold extraction became a more capital-intensive and long-term activity.

Gold was discovered at Gabriel's Gully by Gabriel Read in May 1861 and eventually sparked the rush. Gabriel Read, an Australian prospector found gold, "shining like the stars of Orion on a dark, frosty night" half a metre down in the creek bed.

Gabriel's Gully is near the Tuapeka River above Lawrence about 25km north east of the point where the Tuapeka enters the Clutha/Mata-Au between Roxburgh and Balclutha.

The rush was slow to start due to both disappointment with earlier New Zealand gold strikes and the disapproval of the Presbyterian community of Dunedin, 70km away. But by August of 1861 the fever began in earnest.

A further discovery was made a year later at Cromwell in the upper reaches of the Clutha/Mata-Au.

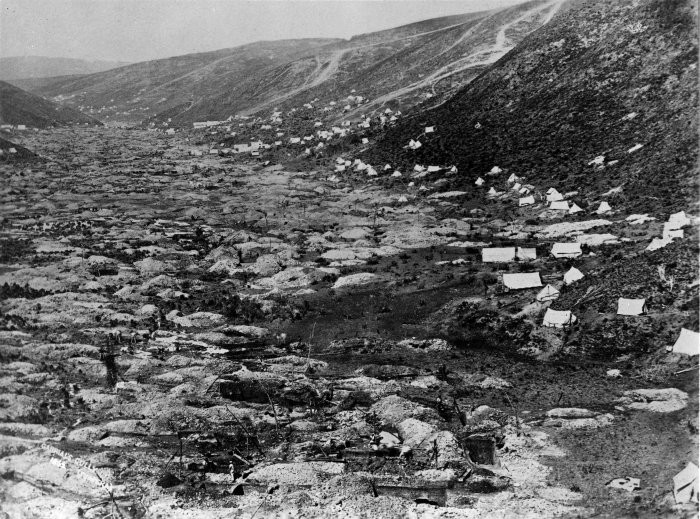

Early miners worked on a small scale as individuals or small groups on alluvial claims in active rivers. As these were exhausted, they moved to higher gravel terraces and areas of more complex geology.

These larger scale operations required raised sluices and water-races (which criss-crossed Otago at this time) to get water to them. These required more capital investment and large quantities of timber. This was particularly so for the cemented gravels of Bannockburn. Dredges required even more capital and led to the growth of New Zealand's nascent stock exchange.

Otago's total reported alluvial gold production was 240 tonnes but does not take account of undeclared gold. Hard-rock mining was on a small scale and produced less than 20 tonnes of gold (University of Otago).

'Many of the earliest alluvial mines were extremely rich (10's or even 100's of grams of gold per tonne of gravel), but most gravels had at most a few grams of gold per tonne' (University of Otago).

However, the alluvial deposits could also be hard to get out. The gold at Gabriel's Gully was locked up in Blue Spur conglomerates which consisted of course schist-and-greywacke cobbles and gravels cemented together by water-accreted limestone and blue-green clay (smectite).

Various methods such as mining, sluicing and eventually crushing were used to pulverise the conglomerate such that the gold could be sluiced out with water - a process that was often grossly inefficient leading to the loss of as much as 50% of the detrital gold in the rock (University of Otago: Gabriel's Gully)

As the surface gold was exhausted new forms of extraction took over: deep-level hydraulic elevating, quartz mining, and dredging. All of which created demand for mechanical and engineering skills and manufacture.

More discoveries were made on distant Shotover and Arrow tributaries of the Clutha/Mata-Au near Queenstown, and ultimately across the whole of inland Otago, the one at Authur's Point creating the biggest rush of them all. The number of miners reached its maximum of 18,000 in February 1864

Later the West Coast gold rush (1865-6) threatened to lure many European miners away from Otago. 'The authorities in Dunedin countered by inviting Chinese diggers to cross the Tasman from Victoria and work the Otago fields under the guaranteed protection of the Otago Provincial Council.'

The Chinese population reached a peak of 5,000 and were renowned for their ability to recover gold from worked-over claims ('tailings'), but also for their skill in prospecting new fields.

Tensions arose between both Chinese and European prospectors and between prospectors and farmers over land use and resulted in the introduction of the New

Zealand Head Tax. In 1881 a £10 tax was set on each Chinese person entering New Zealand. This was later raised to £100 in 1896. It was repealed in 1934 and Prime Minister Helen Clark

offered an apology to New Zealand's Chinese community in 2002.

In the 1890s the Chinese entrepreneur Sew Hoy discovered a system of dredging that 'made it possible for large-scale mining to be carried out on the river-flats for the first time' with a new generation of paddock dredges.

This gave rise to the dredging boom, which exploded across Otago and Westland (Dunedin City Council). The first steam-powered dredge, the Dunedin, worked the gravel beds of the Clutha/Mata-Au for 20 years from 1881 and extracted 530kg of gold.

At the peak of dredging in the early 1900s some 100 dredges operated on the Clutha/Mata-Au, 15 on the Manuherikia, and 33 on the Kawarau and Nevis. The last dredge stopped working at Alexandra in 1963 (Te Ara).

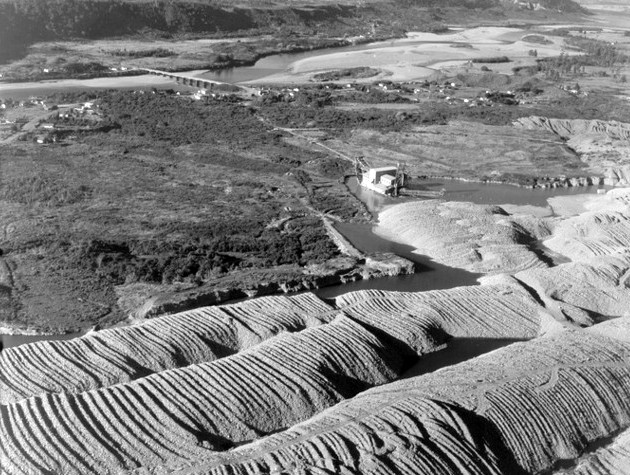

The dredges led to massive disruption of river beds:

In 1920 the Rivers Commission estimated that 300 million cubic yards of material had been moved by mining activity in the Clutha river catchment. At that time an estimated 40 million cubic yards had been washed out to sea with a further 60 million in the river. (The remainder was still on riverbanks). This had resulted in measured aggradation [i.e. raising] of the river bottom of as much as 5 metres. (Wikipedia: Central Otago Gold Rush)

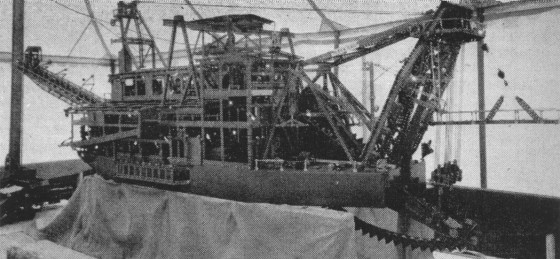

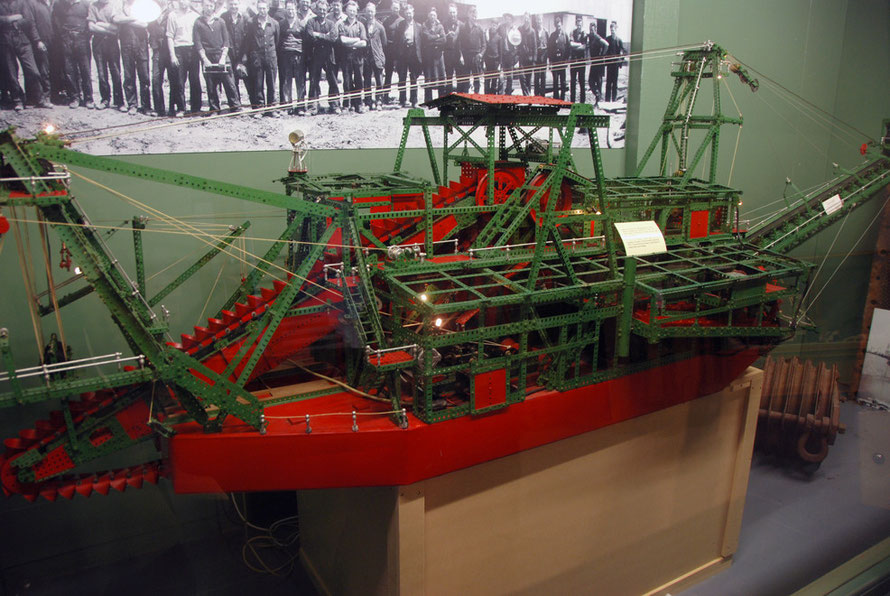

There is a fantastic Meccano model of a gold dredger in the Hokitika Museum which featured in Meccano Magazine in 1956-7.

The prototype operated on the gold bearing flats of the West Coast's Grey River between 3rd December 1937 and 14th September 1954. The dredge used a chain of eighty manganese steel buckets, each weighing 1.7 tons. Each scoop had a capacity of 16 cubic feet. During its years of operation the dredge covered 1,378.5 acres of ground, treated 61.5 million cubic yards of gravel and recovered 164,230 ounces of gold.

The model was built in the 1950s by Blake Huffam, an oilerman sitting his dredgemaster's qualification, who was employed on the dredge. It took him around 3000 hours to assemble the 45,000 parts.

The buckets are not standard Meccano parts, each having been fashioned by hand from tins which originally held condensed milk (See Dalefield).

(See my page Glaciers: Gillespie's Beach for the brief story of the 'universal failure' of the Von Schmidt Suction Dredge.)