The New Zealand Rushes: Gold Maketh the Colony (5 pages)

I. Introduction

'Gold was seen as the magic ingredient that would attract immigrants, transform sluggish economies and deliver instant prosperity to all and great riches to some'.

King, History of New Zealand, p. 207

Introduction

I hadn't really planned to compile pages on the New Zealand gold rushes but sometimes things develop their own momentum.

The discovery and exploitation of gold and gold artefacts figures large in the history of European overseas conquests and colonisation. And the phenomenon of the 'goldrush' is a particular feature of the 19th century.

The discovery of successive gold fields in New Zealand also played a vital role in early settlement and the appropriation of mineral wealth and agricultural land.

So I now have four pages that have something to do with these gold rushes in the South Island.

This page is a general introduction to the gold rushes, the geological origins of gold and its transformation by erosion and weathering into detrital gold.

The second page explores The Otago Gold Rush, which was a rush of major significance and really put New Zealand on the 19th century map for adventurers and diggers.

This page developed out of my page on the Clutha/Mata-Au river which flows through much of Otago and was central to its gold rush (and is New Zealand's biggest river by volume).

The third page is devoted to the West Coast gold rush that followed shortly after the Otago rush.

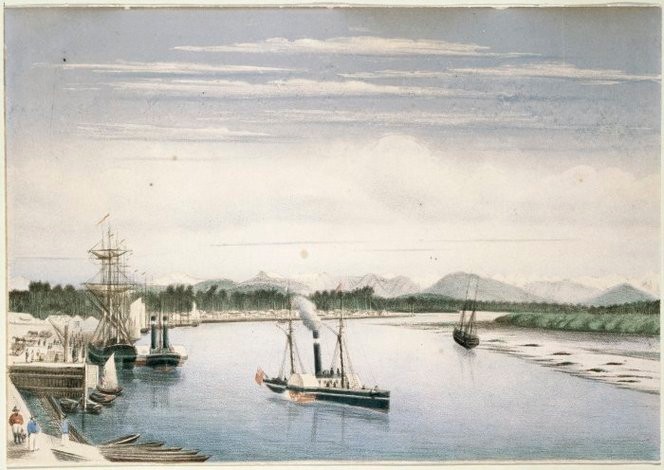

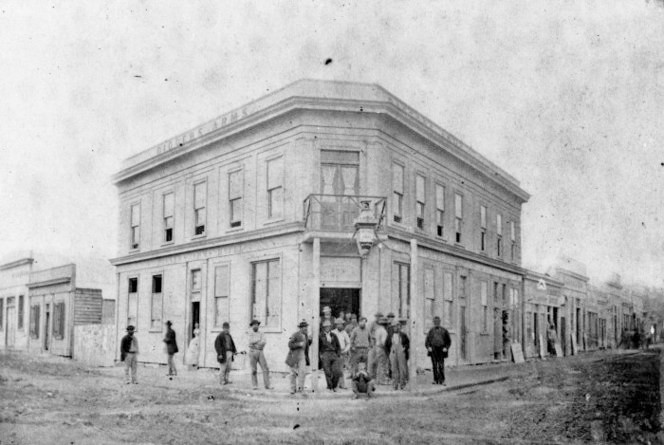

This shifted the locus of extractive effort and led to the rapid development of the West Coast gold mining town of Hokitika (my fourth page) that has recently featured in works of UK and New Zealand fiction - see for example The Colour (2004) by Rose Tremain, Hokitika Town (2011) by Charlotte Randall,and The Luminaries (2013) by Eleanor Catton.

The shift west also required different technologies as major gold bearing quartz reefs were discovered.

These pages have taken me somewhat off the beaten track of our travels and I have borrowed heavily from other websites and photographic sources. I've acknowledged these and link to them.

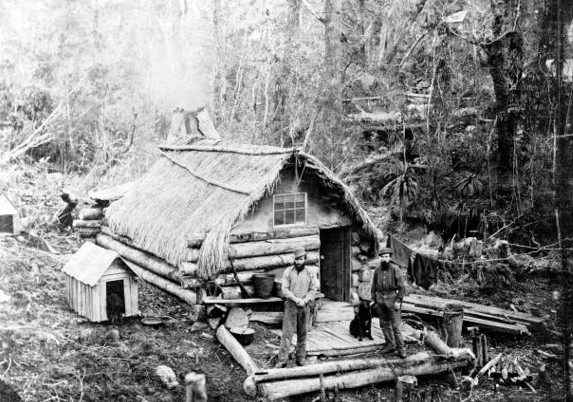

I think I've always had a secret yearning to be a prospector, a fossicker, a 'hatter' even, (an old solitary fellow working a claim by himself).

Whether I could have withstood the rigours of the 19th century goldfield under canvas with plagues of sandflies, mud, danger, disappointment and the sheer monotony of shovelling hundreds of tons of gravel on a tiny claim surrounded by other tiny claims is another matter entirely.

As Tremain has Joseph Blackstone reflect in The Colour,

And yet he also knew, from the hours and days he had worked sifting mud at the edge of the creek, that gold mining is pure drudgery: a drudgery of the body and the mind (p. 138-9).

The New Zealand Gold Rushes

It is not surprising that gold rushes were a phenomena of the mid and late 19th century. By this time vast numbers of young, energetic and capital-hungry people - initially men - were on the move across the colonies of the European powers.

Gold rushes held out the promise of making enough money to set a man up in the New World or to return to the Old World with money to rise out of grinding poverty and limited prospects.

Having broken the bonds of family, place and fixed social position in the Old World the thought of striking it moderately rich was hugely attractive to young and middle-aged men who had not had time or opportunity to become truly attached to their new colonial homes.

In the 50 years between 1831 and 1881 400,000 migrants arrived in New Zealand. Of these roughly three quarters stayed. In the same period 250,000 children were born (King History of New Zealand p.178).

In the 1850s settlement was promoted by provincial government schemes. In the 1860s gold fever was the impetus for immigration. And in the 1870s and 1880s central government schemes, 'attracted immigrants at a rate that swamped all previous experiences and campaigns' ( ibid p. 178).

The non-Maori population doubled between 1861 and 1864 from 98,000 to 171,000 largely due to the gold rushes (ibid p.210).

The influx around gold also changed the composition of the population. Six per cent and four per cent of Westland and Otago were Chinese in 1874. The Irish population also grew quickly to 19% in Westland.

The Geological Origins of Gold

Otago's gold was formed 150 million years. 15km below the earth's surface hot water (over 200 degrees C) was forced through earthquake-faulted sedimentary rocks towards the surface to emerge as hot springs. The water deposited quartz and gold veins into the surrounding rock. These were later uplifted into high mountains of schist and greywacke that over millions of years were eroded away.

Gold is sixteen times denser than water and does not travel far, if at all. As erosion took place the detrital gold was first deposited in layers of coarse gravels on the eroded bedrock. Further periods of mountain building led to the erosion of those gravels and the gold was reconcentrated.

It is reckoned that at least 15 kilometres of rock have been eroded from over present-day Otago. All that remains of that huge upand is the widespread alluvial gold and small amounts of gravel (University of Otago).

The Southern Alps are currently being uplifted at a rate of 10mm a year and eroded at pretty much the same rate (University of Otago:Golden Rivers).

Methods for Winning Gold

Gold can be won in a number of ways.

The simplest is alluvial panning and requires little more than a gold pan, a shovel and a ready supply of water. Such easily worked 'washdirt' was soon exhausted. Gold panning was really used primarily for prospecting rather than extraction and was known as gold 'fossicking' in New Zealand.

The manual working of alluvial and terrace gravels raised the capital requirement of miners. Such gravels had often undergone burial, compaction and cementation and required great effort to break them up to release the detrital gold hidden in them. This could take the form of short drift mining, crushing and sluicing as well as just hard pick and shovel work.

Both these forms of gold prospecting are amenable to individuals and gangs of capital-poor diggers but here the capital required soon rose as getting water to terraced gravels and applying it under pressure become a necessity.

There were three forms of sluicing: ground, hydraulic and hydraulic elevating.

Ground sluicing ran or redirected water over loosened gravels to wash them into sluice boxes underlain by a riffle of stepped metal boxes that were designed to catch the gold. These were notoriously inefficient. The name of the simplest box was a 'Long Tom'.

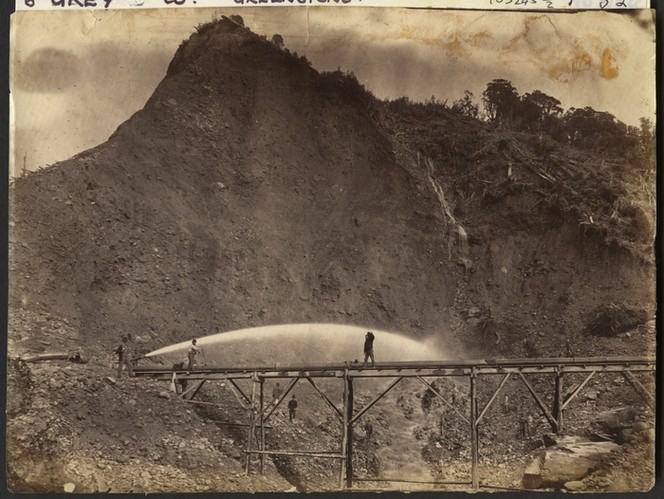

Hydraulic sluicing used 1 to 10inch jets of pressurised water to blast gravel walls to loosen and move debris into sluices. This required huge amounts of water and a head of water of between 100 and 300 feet.

Hydraulic elevating used pressurised water to carry gravels and slurry upwards - often in stages. This allowed pit mining and again required prodigious amounts of water and hydraulic pressure from gravity-fed networks of pipes and water races.

In all mining for gold the proportion of waste rock - the tailings - to gold was immense and the removal of waste a huge issue. The easiest method of removal was to use natural water courses in spate to carry the waste downstream. Moving the waste manually once it had been passed though the sluice box was wasted but often necessary effort (see here New Zealand Gold).

Hard rock mining was the next form of gold mining chronologically in New Zealand. This required much greater capital to both sink shafts to gold bearing reefs and to crush the quartz-bearing rock into rough sands to release the gold using Stamper batteries.

In the late nineteenth century steam-powered dredging on a massive scale became possible. Before this manually operated spoon-dredgers had been used on some rivers.

And lastly vast hardrock opencast mines were established in the twentieth century.

Organising the Goldfield

A claim could be gained by getting a Miner's Right (£1 a year) through the Goldfield Warden.

An Otago claim could not be larger than 100ft by 100ft (10,000 square feet). Diggers could amalgamate their claims in order to gain economies of scale and co-operation as the capital intensity of digging increased.

A claim once staked out and registered could only be left for a few hours in the daytime or at night or on Sundays. Otherwise another digger could legitimately 'jump' the claim. It was possible to buy claims protection from the Gold Warden to allow absences of 14 to 30 days without the claim being considered abandoned.

Gaining access to water for processing gravel was essential and regulated by the Warden through a Water Race Mining Privilege. The Warden would inspect the claim and proposed water race and tail race to ensure it did not rob other miners' water supply nor flood claims downstream of the tail-race (KaeLewis).

The Otago Miner's Right said the following,

Every person residing on a Goldfield and engaged in mining for gold shall take out a Miner's Right, such Miner's Right to be produced for inspection when demanded by the Warden or other

officer or by any person duly authorised in that behalf in writing by the Warden. Every Miner's Right shall before the issue thereof be signed by some Warden acting within the Province of

Otago' KaeLewis.

On Coromandel Peninsula, Māori resisted attempts to open up their lands to gold mining in the 1860s, but little could stand between Europeans and gold (Te Ara).

With the development of the goldfields there was also a development of the social character of co-operation and competition.

The initial prospectors were often lone men working on their own, fossicking through new country with a gold pan and shovel trying different stream beds and gravels.

Once a major find was confirmed the flood of diggers began. River bed gravels could be worked relatively easily and a lone digger could make a go of it. But for many it made more sense to 'go mates' - team-up with others.

This provided some protection and as the getting of the gold got harder it was essential in order to use more sophisticated technologies.

As digging gave way to industrial production techniques - dredging and hard rock mining - more capital was required and the joint stock company came into its own. At this point the freewheeling digger became a wage earner with or without a share in the gold being extracted,

'Those who were struck by gold fever stayed, living out their lives in shacks until they were too old or infirm to work a shovel and gold pan. These old prospectors were known as hatters.

Their passing marked the end of a pioneering era, when men could be footloose drifters who entrusted their fate to gold in the gravel' Te Ara.

The Customs Duty on gold was around 2.4% of its price. Gold could be paid into bank branches although many diggers held onto their gold in the hopes the price would rise. Dust could be used to buy goods and services in the gold towns.

New Zealand Gold Production

By 2003 about 538,640 kilograms of alluvial and 368,544 kilograms of hard-rock gold had been produced in New Zealand (907 tonnes in total.) The total value (in 2003 terms) was US$116.32 billion

(Te Ara).

For comparison it is estimated South Africa has produced some 40,000 tonnes of gold since mining began (Wikipedia).

A total of 174,100 tonnes of gold have been mined in human history, according to Gold Field Mineral Services as of 2012 (Wikipedia).

The Social and Economic Impact of the New Zealand Gold Rushes

New Zealand's total historical gold output is pretty small beer when compared to world totals (just over half a percent).

But it's extent and timing were vital for the course of New Zealand's development. The chart above shows gold production in the different goldfields in the country and the way they developed sequentially, which kept New Zealand's gold in the news for a decade and was given added impetus by a rise in production at the start of the twentieth century.

The gold rushes attracted young, carefree, and relatively skilled male migrants. The unskilled working classes generally lacked the funds to get to New Zealand and sustain themselves until they hit 'paydirt' - that is, enough gold to feed themselves (see Eldred-Grigg 2011 Diggers, Hatters and Whores: The Story of the New Zealand Gold Rushes Chapter 1).

They created demand for a whole range of goods and services - from shipping to retail to brewing to increasingly sophisticated engineering as the capital-intensity of the industry developed.

They gave nascent provisional governments access to revenue streams through taxation that could be used to develop the infrastructure of roads and railways.

And they attracted people into often sparsely inhabited regions where many stayed on as farmers, settlers and miners.

The gender imbalance and the anti-establishment nature of diggers society also hugely contributed to the enduring 'matey' egalitarian culture of New Zealand.

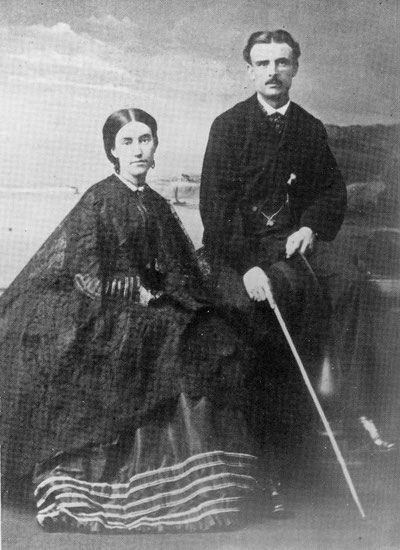

Mary Anne ('Lady' to her readers) Barker (1831–1911), author and wife of the early Malvern Hills (Canterbury) sheep run colonial administrator, Frederick Napier Broome, (pictured below in c.1866) comments in her high handed but engaging manner,

The look and bearing of the immigrants appear to alter soon after they reach the colony. Some people object to the independence of their manner, but I do not; on the contrary I like to see the upright gait, the well-fed, healthy look, the decent clothes (even if no one touches his hat to you), instead of the half-starved, depressed appearance, and too often cringing servility of the mass of our English population. (Station life in New Zealand, 1870 p. 19).

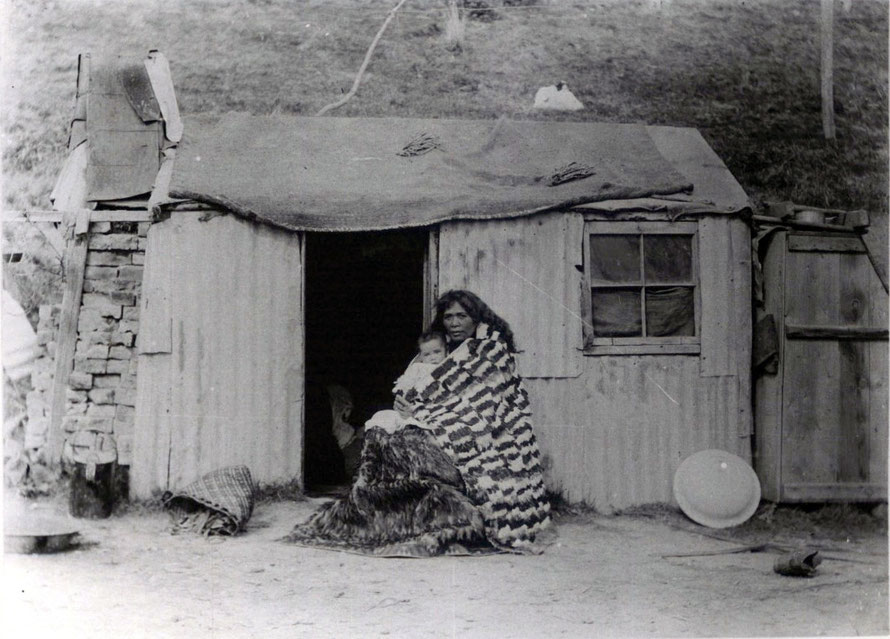

The influx of people into New Zealand associated with the goldrushes was less positive for Maori. The gold rushes helped to develop the infrastructure and awareness for the development of migration from the UK and Ireland. Diggers became settlers. Pressure on land increased.

While there was Maori involvement in gold prospecting and extraction it was marginal. Maori knew about gold but they did not have the metalworking technologies to exploit it. For Maori gold was a distraction from pounamu/greenstone.

Consequently the riches generated on the goalfields largely by-passed Maori who were in a period of what many thought was terminal decline.