IV. And it did rain: Authur's Pass to Dunedin

In which he feels unwell

The drive from the Bealey Hotel in Authur's Pass National Park to the Otago Peninsula turned into a thoroughly unpleasant day. But one from which I have learned an important lesson about hair dryers.

The drive time on the New Zealand AA website from Authur's Pass to Central Dunedin (444km) via Staveley is 6 hours and 31 minutes. We had another 25km of serpentine roads to get out to our 'bach' on the Otago Peninsula. So even on an optimistic basis we were talking seven hours of driving plus time out for coffee, food and photo stops.

I hadn’t slept well and I didn’t feel well. I had a strange pain on the left side of my abdomen. Maybe I had driven too long the day before, slumped behind the wheel. Maybe the waitress’ words – ‘What, chips with venison pie, mate?’ - had come back to haunt me. Or maybe I had been hit, as the Italians say, by ‘un colpo di freddo’ – a shot of cold air – as I stood at the top of Authur’s Pass the previous day in the freezing wind.

Whatever the cause I was a bit crook, iffy, ill, under-the-weather, out-of-sorts, sub-par and something felt amiss.

Anyway after a full breakfast and the worst coffee in New Zealand we set off down State Highway 73 alongside the broad Waimakariri riverbed. The overnight rain had stopped and it felt as if the clouds were lifting. Traffic was sparse to non-existent. The mountains from last night’s stop seemed a little clearer, the cloud just grazing their 6,000 feet tops.

The tree line in the Southern Alps is around 1200m and above this the distinctive alpine flora of New Zealand begins. This is dense and species rich in the west of the Authr's Pass National Park

and sparse and dominated by the inaka (Dracophyllum) and snow totara in the east. Unfortunately we did not see any of this habitat which is ‘one of the joys of present-day New Zealand’ (Gibbs,

Ghosts of Gondwana p.123). But not one we were to see.

The Dry Country of Castle Hill and the Torlesse Range

With remarkable speed we moved from the suffocating beech forest cloaked hills of the western edge of the park and alpine mountain range to the increasingly barren, and dry mountains of the east where rainfall reduces to a mere metre a year.

Once we left the Waimakariri valley the road briefly straightened out into long stretches of golden-grass edged straightness. Indeed, briefly, the road felt roomy. But this was not to last for long.

We drove south between the dry Craigieburn and Torlesse Ranges past lakes Grassmere and Pearson.

I was amazed by the sheer, matt grey and dull sienna mountains that seemed almost entirely composed of scree. Beneath these peaks lie a few small ski areas – Craigieburn Valley, Broken River (with a lift underneath Nervous Knob) and Mt Cheeseman.

It would have been nice to stop and drive up some of the gravel roads that wound enticingly towards the steep dry slopes of the ranges but we pressed on.

The road rises and cuts between Hamilton Peak and Broken Hill and then runs down the side of the sharply incised Cave Stream. To the left were the gaunt limestone boulder fields of the terraced Flock Hill. (These were formed in the New Zealand Ice Ages by glacial meltwater). In front rose the seer Torlesse Range and the Castle Hill, Red, Junction, Back and Otorama peaks. And somewhere there was a 594m-long cave carved out of limestone.

The limestone tors on top of the hills were pale spectres in the shifting milky light. They reach their climax at the distinctive formations of Castle Hill – which is one of the top bouldering sites in New Zealand.

Mounts Cheeseman, Izard, Cloudsley (click here for Mt Cloudsley web cam) and Enys and the ghoulishly-named Dead Man Spur behind Castle Hill were ash grey and catching the light in an ethereal way. It was hard to tell if they had substance and what size they really were. The ridge between them runs at nearly 2,000m and Mt Enys is 2,194m (7,198ft).

A Cornish Connection

Mt Enys is named after John Davies Enys, the second son of John Samuel Enys and his wife, Catherine Gilbert, who was born on 11 October 1837 at Enys in Penryn, West Cornwall.

John Enys emigrated to New Zealand and unsuccessfully ran the Castle Hill sheep run with his brother (the farm was kept going with the larger Enys family's money). Like Guthrie-Smith (who wrote the classic account of a Hawke's Bay sheep run on the North Island, Tutira: The Story of a New Zealand Sheep Station, 1921) John Enys had been educated at the topnotch private UK school, Harrow.

A keen botanist and collector he entered public life as a justice of the peace in 1865 and held other posts in the Canterbury area. The Enys brothers were known for their hospitality at Castle Hill but given the frequent absence of one or the other of them, usually in the UK, were known as 'the buckets in the well'.

The menace of wilding trees

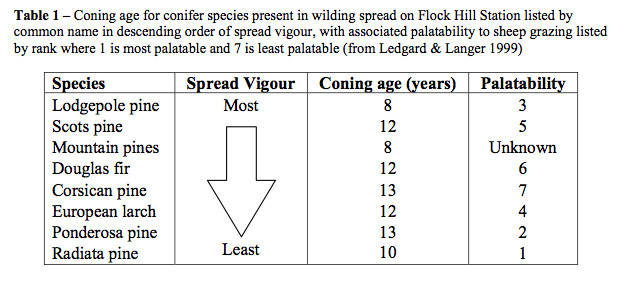

Whilst on matters botanical there is an interesting report on the spread of 'wilding trees' - mainly introduced pines and particularly the lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) - in the Flock Hill area.

Wilding trees represent one of the most serious threats to the biodiversity and large open montane landscapes that define the high country of the South Island. In this context we are referring specifically to the uncontrolled spread of introduced conifers.

They can produce thousands of seeds after only 6-15 years of age, depending on species and site conditions, and these can be wind-dispersed distances up to or exceeding ten kilometres depending on the situation.

Wildings are long-lived and capable of out-competing other plant species in nearly all communities except dense forest. As such they can rapidly change the ecology and dynamics of large areas of land.

(Darrin Woods, Wilding Conifer Management for Flock Hill Station,2007)

It is reckoned 210,00 heactares of public land in New Zealand are under threat of wilding pine invasion http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilding_conifer.

The Broken River Karst Area

If only we had had more time we would have stopped and explored this remarkable area of limestone mountains much of which falls in the

Korowai/Torlesse Tussocklands Park. Here there grows the remarkable Vegetable Sheep - an alpine pillow or pin-cushion plant (Haastia pulvinaris). But it was not to be.

'The Broken River karst area ... is nationally important for its landscape, geological, geomorphological and botanical values. The Flock Hill scarp and its limestone tors are a distinctive landform. It is a refugia for many rare limestone plants such as the limestone forget-me not (Myosotis colensoi) and limestone harebell (Wahlenbergia brockeriei), and is the locality for Seligeria dimunata, a moss endemic to the Flock Hill tors.'

(Darrin Woods, Wilding Conifer Management for Flock Hill Station,2007:11)

Again, the miles that lay ahead of us cut short any exploring and I had to make do with some snapshots from the car. Back in the UK I forgot just how huge these rocks are until two specks on one of them turned out to be people (see below).

The Endurance Test

The rest of the day became something of an endurance test.

The road quickly slopes down onto the broad Canterbury Plains and after a cup of coffee at Springfield and a photo of the Sheffield Pie Shop we turned west along the 'Inland Scenic Route South'.

Just beyond Sheffield the cloud descended to the treetops and the rain started. We went through places called Glentunnel, Glenroy and Windwhistle. We crossed the huge wash of the Rakaia River and pressed on along lonely, pine-bordered roads as the rain reached a deafening intensity.

There was something gaunt and sinister about those field-bordering trees, probably coastal lodgepole pines, often hacked off halfway up to provide better shelter belting, and with limbs growing topsy turvy and again shorn off with what looked like little care.

Even the bristling green of superphosphate-pumped grass was tuned down by the flattening rain with the trees stark against it and the mist.

The rain was incessant, cold and grim. I felt ill and a long way from home. We had to grind out the miles into the wind and not think of the spectacular views we were missing back up to the Southern Alps.

Later, talking to a bloke from Christchurch who'd driven down to the Otago Peninsula the same day said he’d never experienced rain like it.

We inched forward through wind-driven waves of water past Alford Forest, Brushside, Stavelely, Mount Somers, Mayfield and Geraldine - yes, that's right, "Geraldine". The Inner Scenic Route (which

had been anything but scenic) came to end and at Orari we joined the main Christchurch-Dunedin road.

Joining the slow, crowded, single-carriageway main road did not improve matters. We passed by Winchester and Temuka and then a slow crawl through the many traffic lights of Timaru (pop. 42,865).

I thought we were skirting Timaru’s main centre but looking at the map now we went straight through it. It felt like driving through the strip-development of an American town.

Shower after squall after shower came barrelling up State Highway 1. The roadside riches of Timaru had been replaced by a desert – sodden fields and turn-offs to places like Otaio, Hook, Makikhi, Nukuroa, Willowbridge, Gum Tree Flat, Elephant Hill and Dog Kennel - that's right, 'Dog Kennel'. There were no funky pastel-shade painted cafes selling coffee and muffins here.

We passed a big construction site. It turned out to be a processing plant for making dried milk to feed the growing markets of China and Asia.

Eventually I was forced to stop at the Glenavy Store by the sciatica-like pains in my right leg.

It was not a cheery place, perched right on the main road and desolate in the cold wind. The woman inside was pleased the milk-drying plant was being built. 'It might bring in a bit of business', she said looking up briefly around the empty shop.

The NZ$214 Oceania milk plant opened for its first intake of milk in the first week of August 2014.

48 suppliers have signed contracts for the supply of 170 million litres of milk in the 2014-15 season. At full capacity, the plant will be able to process 300 million litres of milk each year,

generating 47,000 tonnes of milk powder (see CountryTV). Shortly afterwards the price of milk in New Zealand fell to a five year low on the back of slowing growth in China and sanctions

against Russia's adventures in Ukraine.

There was a notice for a salmon fishing competition in the Glenavy shop. It seemed to involve drifting down the Waitaki river on rafts. (In fact it was a fundraising event using 500 plastic salmon - see here.)

We pulled across the road from the store into a little park and I walked in the rain and felt low. I read a sign about the Ariadne - a yacht run aground in Waitaki Bay in 1901. It felt like Glenavy was struggling to put itself on the tourist map.

The toilet offered by tiny Glenavy was pretty stinky and we pulled back on to the road to stop by huge, forbidding wash of the Waitaki River, renowned for its salmon fishing and cold, turquoise water. The toilet here was no better but needs must, eh.

On and on the road went. 'Oh for a big camper van', I thought so that we could stop and make a cup of tea and lie down for a bit and let the wind rock and roll us to sleep.

The list of places passed went like this: Oamaru, where I stopped for petrol, Maheno, Herbert, Hampden, Moeraki (where Keri Hume takes her characters in The Bone People for a holiday), Palmerston, Waikouaiti, Waitati and finally the steep descent into Dunedin. All the time in low cloud, pressed between the unseen Pacific coast and the shrouded hills.

I could feel my energy ebbing away, that familiar ache of flu creeping into my hands, my sense of vulnerability and sensitivity to the cold and wind crying out for a warm house and a soft bed.

Little did we know but we were passing the site that transformed New Zealand agriculture. On the massive Totara Estate, on the state highway 8km south of Oamaru, the first plant was established to freeze New Zealand lamb for transportation to the UK in 1882.

The 15,000 acre estate was owned by the colossal Scottish-owned New Zealand and Australian Land Company. Previous to the advent of refrigeration sheep were kept on huge 'runs' and only the wool could be exported. This made farms singularly dependent on global wool prices.

Old sheep were a real problem to dispose of - in Tutira: The Story of a New Zealand Sheep Station (1921) by H. Guthrie-Smith - they were sold at a pittance to a neighbour to feed to his pigs. In other places they were stunned and thrown off cliffs into the sea.

The shift from huge, extensive farms for wool to farms for lamb and mutton allowed a smaller owner-occupier farming class to develop and the government of the time passed various Land Acts that

allowed for the fully-compensated break-up of big estates that had rapidly created a new aristocracy from the like of which many migrants to New Zealand were attempting to escape.

By 1902 frozen meat accounted for 20 per cent of New Zealand's exports.

Ironically, the area around Oamaru has petty much gone over lock-stock-and-dry-milk-barrel to dairy farming.

Digger and Lynn McCulloch, who farm at Glenavy, are holdouts against the general trend and have recently been promoting their lamb in the US on a trip organised by an Oamaru company, Lean Meats Ltd.

Digger McCulloch is a third-generation farmer on the 284 hectare property which has 2000 ewes, 500 hoggets (yearling sheep not 'little hogs' as I at first thought) and 150 cattle.

The McCullochs are optimistic about the future of sheep and lamb in New Zealand. Numbers have declined and prices gone up as the migration to dairy got under way. And New Zealand is well placed to service the growing demand for meat in Asia.

Back on the road Dunedin was bad-tempered blur and trouble was a-brewing. We fired up the satnav (almost completely superfluous in the South Island) whilst hoping to find an electrical shop to buy a hair dryer to replace the one that had gone 'kaput' at Authur’s Pass.

With the strange tunnel vision of the terminally tired driver I obstinately followed the stanav’s direction over a flyover and on to the road to the Otago Peninsula. We were quickly out of the town and shoe-horned onto the winding road that runs along the the side of Otago Harbour with steep hills rising above us. Without a hairdryer.

We needed supplies and I stopped at a little shop at Macandrew Bay. In desperation I explained my hairdryerless predicament and the volcanic eruption that was brewing back in the car to the shopkeeper as if she would miraculously produce a hairdryer. But she didn’t and nor did the pharmacy.

I was bone-tired, road-weary band sick. We stopped at a more promising shop in Portobello. Parking was rationed to five minute slots by a sort of egg-timer but I was beyond caring.

I bought eggs, bacon, milk, bread and wine. Things were looking up, the cloud lifting. Radio silence between us was broken. But they too had no hairdryer.

Later one of the women in the shop told me she was going to London to stay in the Youth Hostel behind St Paul's Cathedral in the City later in the year. I could not think of a greater contrast. I hope she had a good time.

We followed the satnav instructions onto gravel roads around Hooper’s Inlet and over the spur to Papanui Inlet.

We found the house, then realised it was the wrong house. The we found the right house. We made our way down a ridiculous, uncared for path canted and zig-zagged across the vertiginous slope to 'Betty’s Bach' by the waterside. With some ingenuity I worked out how to use the luggage winch to port our mass of gear down to the house.

It was a lovely spot but I was in no mood to enjoy it. A neighbour let us know we were parked in the wrong space. I struggled back up the ridiculous, slippery path in the blackest of moods and gave the bloke the darkest of looks.

As I panted at the top of the climb he made some stupid joke about me not being fit, eh? If I'd had the strength I like to think I would have punched his lights out. With much revving of the engine and dead flat looks to the pinched pair watching us I parked the car over the vertiginous slope that rushed down to the water.

I slid back down the ridiculous path and climbed into the crisp bed with the view over the inlet and the hills on its far side and shivered myself warm. I thought I was on my way down to the Bone Yard with a vicious bout of flu - something that has happened to me both times we've stayed in New York and each time knocked me out for two weeks cold.

The wind picked up in the night, blowing hard. It sounded like someone was standing underneath the bach's raised end and stamping down cardboard boxes with size 14 boots. Clomp, bang, rattle. Rattle, bang, clomp.

In the morning I felt rested, whoozy, but the stirrings of flu had melted away into a mild headache and a susceptibility to the cold.

I got up (somewhat heroically) and made eggs and toast and coffee in the tiny kitchen while 'The Principal', my long-suffering partner tried to dry her fresh-washed hair from the bach's decking in the boisterous south-westerly gale sweeping down Papanui Inlet.

I felt I had learned an important lesson.

Two 'Learning Points' from the drowned out day

1. A bach (pronounced 'batch') or crib (in the southern part of the South Island) is usually very modest holiday home or beach house.

A humorous definition of a bach is "something you built yourself, on land you don't own, out of materials you borrowed or stole."

2. An hairdryer, (pronounced 'you selfish, self-obsessed bastard, how could you

go by yet another shop without stopping. Stop the car!') or 'rotating volume styler' is an essential accompaniment to the 21st century and to be replaced immediately it shows signs of breaking or

has indeed broken. Like-for-like or better-than-like replacement is always recommended. These items are not available in Macandrew Bay or Portobello on the Otago Peninsula.

A humorous definition of an hairdryer is 'something you borrowed without asking for and used for something for which it was not designed - like driving water out of a windscreen-wiper motor on a freezing December morning - and for which you will now dearly pay.'