Authur's Pass III: the pass, the park and passing trains

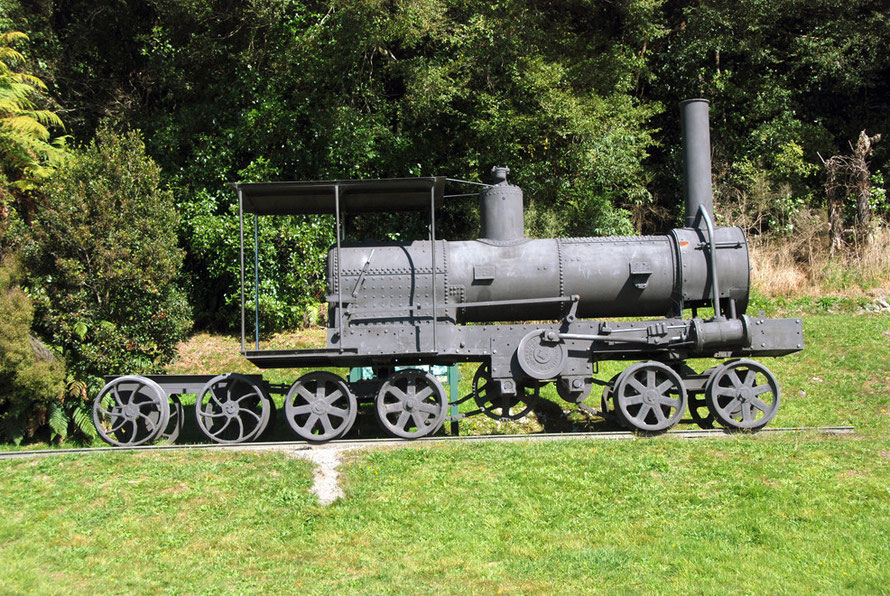

The Davidson Bush Locomotive

Not far beyond Reefton we came across the Davidson Bush Locomotive at the junction with Donaldson Road just beyond Ngahere.

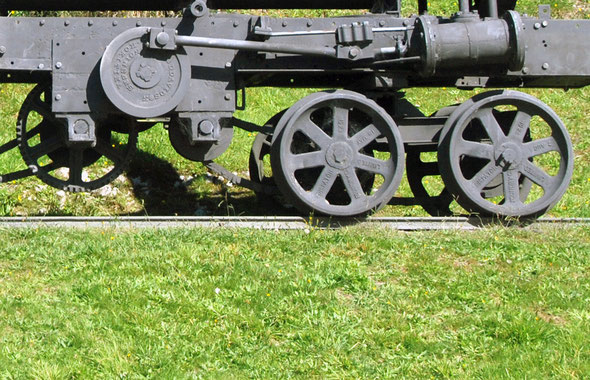

Built as the penultimate loco in a series of 26 from the Hokitika foundry of G and D Davidson the Bush Locomotive was a steam locomotive pared down to its essential parts.

Designed for hauling logs on bush railways in the vibrant logging industry on the West Coast all superfluous parts have been stripped away. There are no big driving wheels and complicated pistons here but a robust chain mechanism feeding from diminutive pistons to modest bogies.

There is no cab but a simple steel plate to stand on and a steel plate for shade.

This Davidson Bush Loco worked until 1942 at the Donaldson saw mill. It was used to tramming logs to the mill and then take timber from the yards to the railhead. It came to rest on the siding where it now stands akimbo to State Highway 7 and was lovingly renovated.

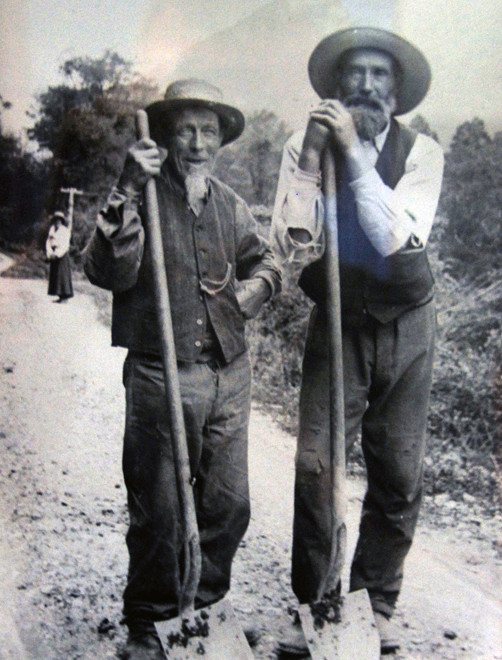

As with so much of New Zealand, the first settlers in the Grey River Valley were loggers. The valley floor was covered in first growth Rimu and Kahikatea forest that rendered beautiful timber. This was first exported from Greymouth and used in the gold industry and once road and rail links – the Otira tunnel below in 1923 - had been established carted to the growing east coast settlement of Christchurch (for more on these trees see my page New Zealand's Podocarps).

Approaching the Authur's Pass

As we neared the mountains the clouds closed in.We stopped at a roadside shop in a little place called Moana to buy coffee and a few bits and pieces - a peanut chocolate slab amongst them – for the journey up the Pass.

We drove down to the lakeside and I climbed a pedestrian bridge over the railway line to take a couple of pictures. In the process I dropped my lens cap from the bridge. I scuttled down onto the line’s ballast and eventually found it. The day was passing and we had covered some miles. It was 4.15pm. I ran back to the car.

(I eventually lost the lens cap for good on Ulva - the amazing 'bird' island near Stewart Island. The cap rolled off the wharf at Post Office Bay while we were waiting for our water-taxi lift back to the main island - see Ulva Island .)

Back on the road we passed through flat valley bottoms surrounded by dark brooding, wooded hills: Paddock and Granite Hill and the Alexander Range. Then through the tiny settlement of Inchbonnie before rejoining the main road (State Highway73) at Jacksons on the broad wash of the Taramakau River.

We stopped and took pictures of a Midland Line train hauling coal going up the grade to the Otira Gorge. It wasn’t going fast because we soon overtook it and stopped to take more photos at the washed-out Kelly’s Creek – a desert of grey rock two hundred metres wide. The co-pilot squunched up into the nearside corner of cab of the double-loco-ed rig waved, smiled and urged the train on with his shoulders.

The Otira Tunnel

We lost track of the train and turned sharply south into the much narrower Otira valley, hemmed in by mountains that rise sharply to 1,400m from the river-wash floor (300m).

It turned out the train had entered the 8.5km/5.3 mile-long Otira Tunnel that climbs from 250m (820ft) to emerge at Authur’s Pass village (760m 2,500ft) on a gradient of 1:33.

Authur's Pass village was originally a construction town for the tunnel which took 16 long years (1907-23) to bore through wet shale and rotten rock. It was the longest tunnel in the British Empire at the time of opening and was to use a complicated mix of doors and fans to extract exhaust gases from steam trains.

Labour troubles bedeviled the first contractors for the tunnel – McClean and Sons – who eventually went out of business though released form the contract by Parliament in 1912.

The Department of Pubic Works took over. By the time the tunnel was broken through electric trains had become feasible and given the length of the tunnel and exhaust gas issues the tunnel was

electrified using electricity from a coal-fired power station built near the Otira end of

the tunnel.

Before the opening of the tunnel travel options ‘over the hill’ (as it is referred to in The Stone People, 1985) were limited: for freight a bullock team and for passengers the Cobb & Co stagecoach.

Alpine Rainfall

The valleys here with their broad riverbeds of slate-grey rubble - greywacke (a hard mudstone) - are brutal and elemental. We had struck them after a long dry period and the braided rivers themselves were lost in the jumble of imposing wash.

Here you really get a sense of tectonic vigour of the Southern Alps and the gargantuan forces at work along the Alpine Fault as the Pacific and Indo-Austrailian plates collide slipping 30mm a year - 'very fast by global standards'.

It's not for nothing that New Zealand is known in some quarters (Australia) as the 'Shaky Isles'.

The Torlesse Terrain rocks of sandstone and greywacke weather to thin soils that are quickly leached. Rainfall is monstrous at 5m (16.4ft!!) a year.

(Snowdonia, one of the wettest areas of the UK gets 3m (9.8ft) for comparison and the wettest area in Europe in Norway's fjordland gets annual precipitation of 3.6m.)

Annual rainfall declines rapidly moving east - 4,500 millimetres at Arthur's Pass village, 1,500 millimetres at the Bealey 15 kilometres to the east, and 1,000 millimetres at Mt White further east.

Arthur's Pass village gets 180 rain days per year and much of this falls in short, high intensity storms (250 millimetres - nearly 10 inches - in 24 hours is not uncommon). These deluges cause severe flooding of streams and rivers. Stone and mud avalanches can lead to loss of life as on the Haast Pass in 2013 where a landslide killed two Canadian tourists in campervan on the main road.

Death's Corner

We pushed on the skies ever-darker through Otira and into the gorge passing first Windy and then Starvation Points before stopping at Candys Bend to take photos.

A sharp wind blew up into our faces. Bare rock walls and vast scree slopes towered above us, the clouds scraping the peaks of Mts Stuart, Philisitine, Rolleston and Temple.

At Wharnocks Knob the road is raised on an overpass across a great slope of shifting scree. A concrete roof protects a section of the road from falling rocks and a vast chute takes run-off over the road.

By now the gradient had really jacked up and I overtook a large purple campervan, much to The Principal's horror.

At the top of the pass – 920m – it was colder and bleaker still. We doubled back up a side road to look out over the old ‘Death’s Corner’ route. A sign warned us not to feed the Kea but they were not stupid enough to be hanging around in the gelid mist belting by.

We pressed on with huge semi-rigs taking stock to Christchurch squeezing along the narrow road. We stopped at Authur’s Pass village to try and get wine but the 'Bottle Shop' was locked up tight. We heard the shrill cry of Kea (New Zealand’s unique mountain parrots) and saw a group of them squabbling near the exit to the Otira Tunnel.

The names of the paths and features give a sense of the desolation and grandeur that confronted early settlers and gold-rushers – Avalanche Creek, Lake Misery, Bealey Chasm, Bridal Veil Creek, Klondyke Corner, Mount Horrible, Cornishmans Rise, Bretts Stream, Paddys Bend and Corner Knob.

A strange mix of the prosaic and the familiar, memories of those who passed through or tarried in the hostile terrain hung from the features of the land like flags and emblems.

The Pass had also been a vital pathway - ara hikoi - through the mountains for Maori seeking greenstone - pounamu - on the West Coast. The pass was discovered by Sir Arthur Dudley Dobson (1841–1934) who had surveyed the first possible trans-alpine crossing in 1864 on the advice of a West Coast Māori chief, Tarapuhi.

Authur’s Pass township was initially called 'Camping Flat'. It was later known as 'Bealey Flats', when a construction camp for the Otira Tunnel before being renamed first 'Authurs' and then 'Arthur’s' Pass. The apostrophe has been much contested and in 1975 the Post Office conceded to replace it after protest from villagers.

The 251km/156m road between Christchurch and Hokitika was opened in 1866.

Coming out of the tight valley of the Bealey River we broke into brilliant early evening sunshine slanting down the wide Waimakarirri valley. This lit up the imposing peak of Mt Williams (1718m/5636ft).

We crossed the 500m-wide riverbed of the Waimakariri at Klondyke Corner by a long, single-file bridge and drove up to the Bealy hotel set on a spur above the desolation of the river, the sun turning the sparse waters into a meandering snake of silver.

I later learnt that the author of the great work on New Zealand vegetation (1992 OUP), Dr Peter Wardle (78), died while crossing the Waimakarirri with a group of trampers (walkers) in 2008.

The hotel was a strange place, huge piles of firewood waiting to be stacked, a separate section of motel rooms and apartments below. The main room was a garish mix of old artefacts and big windows looking out on the Polar Range to the north across the river – The Spike, Dome, Pyramid and Mts Williams, Bowers, Wilson and Scott (this last at 2,009m).

A TV playing rugby league dominated proceedings and an affable bloke with bad teeth from Western Australia was keeping it all altogether.

We had beers - the excellent Speight's draft bitter - and watched the light turn on the shrouded and savage peaks and dark walls of beech forest. Three blokes sats at a table raised on a barrel-end eating and watching the rugby – hard to tell what their trade was.

We had venison pie and the fish at a windowside table. A fragile American woman and her husband sat across the way. The waitress was most surprised that I wanted chips with my venison pie. Which seemed strange as men with bigger appetites than mine have passed this way for many a year.

In the night the rain started and kept up for hours. The room was sparse with enough beds to sleep a platoon and looked out in the morning onto the misty, extravagantly wide braided river.

We had big breakfasts while the TV was tuned to an endless infomercial about skin products. The caretaker/manager bloke told us about the winter and power cuts, how he’d retired after running different businesses (including a shearing run with 50 blokes) both in New Zealand and Western Australia.

He'd returned to New Zealand after his Australian dad had advised him to but retirement didn't suit him. He said, ‘I can only cut my lawn so many times a week.’

He had needed to keep busy and was helping out a mate who he’d helped buy the hotel in the first place, or so it seemed.

The coffee was terrible – the only really bad cup of coffee I had in New Zealand – but that was because the machine was down in Christchurch getting fixed after someone had broken it.

The weather forecast had been promising a front coming up from the south west and we hoped it was passed and through but later that long day of driving east and south we ran into curtains of relentless rain that forced us to a crawl on the Inland Scenic Route South.