To Authur's Pass: Gold, coal, timber, trails and tragedy

Mountains + distance = time

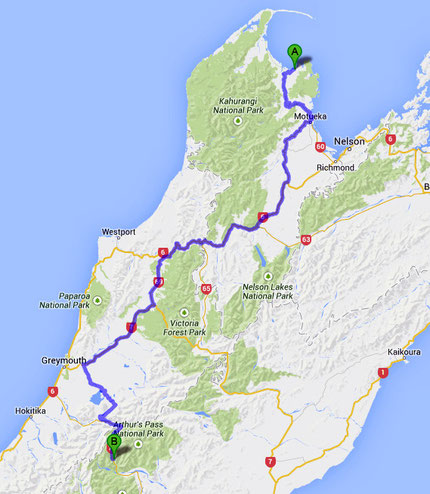

On Day 17 of our trip we left the warmth and bonhomie of our beachside villa in Pohara in Golden Bay in beautiful sunshine and set the controls for Authur’s Pass.

Three things I had gradually learnt in New Zealand, dinned into me by brute experience:

- that the route from A to B, particularly on the South Island, is never straight;

- that driving times were almost always more than our and the internet’s best estimates;

- and that the mountains are not like Welsh or Scottish mountains that you can generally drive around.

The Mountain Passes

In the entire length of the South Island (about 840km – 520m) comprising Fjordland, the Southern Alps and associated ranges - there are only six roads between the East and the West coast.

Of these five use high passes through the mountains: Authur’s Pass (920m), Lewis Pass (900m) Takaka Hill (700m) Hope Saddle (637m) and Haast Pass (450m). The sixth, the road to Milford Sound via the Homer Tunnel (920m), is a very long and very dramatic cul-de-sac.

The size and extent of the mountain ranges makes for some considerable detours. For example, as the crow flies the distance between Milford Sound and Queenstown is about 70km. The road distance is 291km and travel time without stops is forecast at 5 hours and 5 minutes (Realjourneys NZ).

Our journey to Authur’s Pass initially took us over the Authur Range and Takaka Hill via the spectacular Eureka Bend (that was down to single file due to a rockfall). The road here reaches a height of 700m (2,300ft) before dropping down into Motueka.

We stopped briefly here for coffee and supplies and then turned due south to follow the Motueka valley – full of vines, hops and soft fruit and where Keri Hulme in The Bone People worked in 'the tobacco' - to the Flat Rock Café to join State Highway 6 heading south and then west to the Hope Saddle (637m – 2,089ft - opened in 1879) before dropping down into the broad Gowan valley (presumably as in ‘gowans’ – daisies in Robert Burns’ Auld Lang Syne) and the Buller River valley and gorge.

The roads were remarkably quiet with the occasional logging lorry and camper vans. The sun shone and dark green pine and beech woodland was ubiquitous, clothing the ranges that stretched far away to the west and south.

The Buller Valley

We pulled off the road at Raits Bridge (260m) between Owen Junction (site of the former Owen Junction Hotel – see below) and Owen River to take a few photos of the upper Buller river and stretch our legs.

The river ran in a tree-lined bed in a broad valley. The fast flowing water was crystal clear.

After the Owens River joins the Gowan River the Buller River, as it now becomes, turns sharply south west in a narrow valley below the Blue Cliffs Range to the west.

At Murchison (pop. 496) it turns west and the valley briefly opens out into the Four Rivers Plain where the Buller is joined by the Matiri, Mangles and Matakitaki rivers. Shortly afterwards the river and road enter the tortuous Upper Buller Gorge.

The Murchison Earthquake

Murchison is the self-proclaimed 'White Water capital' of New Zealand. It was rocked by a 7.8 magnitude earthquake in 1929 (for comparison the destructive Christchurch quake in 2010 was 7.1) that killed 17 people, mainly in landslips.

The paddocks in this part of the Buller Valley are amazingly green and are irrigated from the rivers by sprinkler systems.

We briefly also got great views of the looming Glasgow Range (1459m) to the north west.

It was a driving day and we pressed on snacking on supplies we had bought in Motueka. Since crossing the Hope Saddle the country had felt very different from the rather benign openness and bright sands of Golden Bay.

The Upper Buller Gorge road demands complete attention and the river itself is shielded by the thick forest of the Brunner and Lyell Ranges. The weather had been particularly dry in New Zealand’s late summer and the water was disappointingly low when we could see the gorge.

Two views of the Upper Buller Gorge in end-of-summer low water

Lyell no more

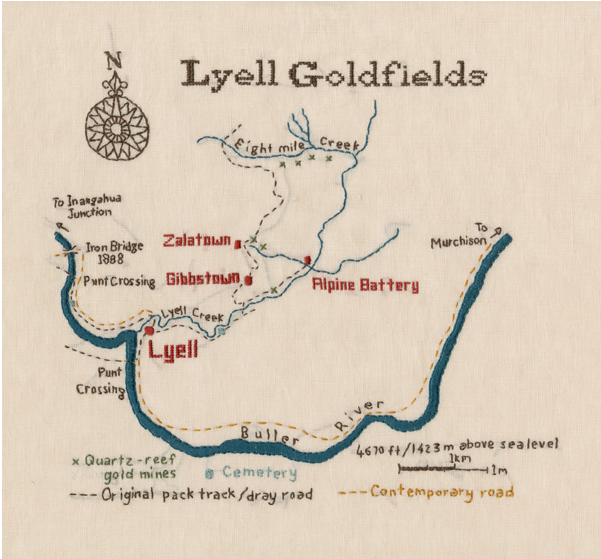

We stopped on a tight bend at a well-organized pull-off at Lyell. This turned out to be the site of one of the biggest gold mining settlements on the South Island during the West Coast gold rushes. Lyell is named after Sir Charles Lyell, a Scottish geologist attributed with developing the theory of tectonic plate movement.

The township of Lyell grew as the news of alluvial gold discoveries – a 19.5 ounce nugget was discovered by a Maori prospector named Eparara – spread to other New Zealand goldfields from 1863.

It was a hugely difficult place to get to and initially only accessible by canoe and rough horse tracks. The alluvial gold was soon exhausted – although with some spectacular nugget finds of up to 50 ounces – and production shifted to the gold-laden quartz in the nearby reefs.

This required heavy machinery (stampers) to crush the rock. This was imported from Melbourne, Australia. At its heyday the largest mine, United Alpine, employed 200 men.

Lyell declined from 1896 and by 1906 when United Alpine closed people moved away in droves.

Disastrous fires and the 1929 earthquake – which closed the Buller road for 18 months – further reduced the town and by 1951 all that remained was the Post Office Hotel, which in turn burned to the ground in 1963.

There is no sign of the place now but for a cemetery that I didn’t visit but there is a 'gold fossicking reserve' where tourists can pan for gold. I got out of the hot sun and stumbled down the zig-zag track to the river bottom but the sandflies were terrible.

My travelling companion was feeling decidedly crook after too much Pohara-style bonhomie and stayed in the car. This was our first real encounter with the dreaded sandfly of which more later.

The Ghost Road

The route from Nelson to Lyell followed by prospectors was arduous until the Hope Saddle road was finally opened in 1879. Before that,

‘the diggers trudging from Nelson came up the Wai-iti or Motueka Rivers to Gordon (now Golden) Downs, crossed “Berneygoosal” (Kerrs Hill) to the Motupiko, then tramped up Rainy Creek and over to the Buller River at Station Creek. Then they continued up the Howard, over the Porika Track to Rotoroa, and down the Mangles Creek to Hampden (Murchison)’

The difficulties of communication at Lyell led to a quest to create a more advantageous route to the west coast rather than that through the Buller Gorge to Westport - some 63km distant.

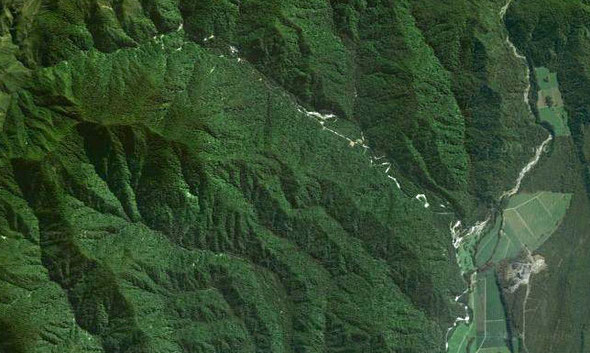

A new route was surveyed north over the Lyell Range (Rocky Tor 1,456m) to connect with the Mokihinui river system. The road was started but never finished and is known as the ‘Old Ghost Road’ and is being turned into a spectacular and arduous cycle trail.

I’m no surveyor but looking at the map the new road looks about twice the distance to the west coast as the admittedly difficult road to Westport.

There’s a video of cyclists being helicoptered up the trail to ride it back above with some great shots from the chopper of the track on the Lyell Range. The video and the ride then goes downhill.

Below that is a shorter video which has some excellent quality chopper shots of riders on the trail.

Mary Smith

We continued on down the gorge and took Highway 69 south at Inangahua Junction which runs up the river valley to the coal mining town of Reefton between the Paparoa Range (1485m) to the west and and the Victoria Range (1640m) to the East.

I stopped and took photos of a huge facsimile gold miner’s wooden barrow full of flowers and a tiny cemetery.

The inscription on one of the few gravestones was to ‘Mary (Wife of) Alfred Smith Drowned in the Buller River 4th Jan 1908'.

This was reported in the Otaga Daily Times of 7th January 1908. The brief notice stated that Mary was the wife of a well-known cattle dealer and that, ‘she was bathing with two younger women, and walked out in shallow water, but stepped over a ledge into 8ft of water, and was drowned.’

Mary (Polly) was the daughter of John and Mary (nee Hoult) Ribet of Hope Junction. Mary Hoult's father, Joseph, had arrived in New Zealand from England in 1842.

John Ribet was born in France in 1835 and settled in New Zealand in the late 1850s. He was for many years the owner of the Hope Junction Hotel (also known as The Kawatiri Hotel- see photo below). Apparently Mary’s husband Alfred went into bankruptcy and moved to Lyell. Mary’s younger sister, Nellie, was married in their Lyell home in 1897.

Ribet initially resisted the temptation to prospect for gold concentrating instead on providing services to other diggers but in 1882 when gold was discovered in the quartz reefs of Mt Owen behind the hotel he formed a syndicate called the Golden Fleece Quartz Mining Company. But the reefs on Mt Owen were never productive and abandoned as fruitless by 1890.

Ribet became financially overextended. Of the Ribet’s seven children two were still born and one died in her first year. Two daughters then died of consumption. In February 1890 John went out

walking with his dog along the Owen’s River and never returned: his body was never found. Daughter Mary died 8 years later in the drowning. Mother Mary Ribet died in 1910 at the age of 72 (see

Anne McFadgen in The

Prow).

The Fuzz

The road to Reefton runs in two ruler-straight runs and it was on one of these that we were puled over by the police – ‘the fuzz’ as Keri Hulme calls them – for a routine check.

After checking my driving licence – which I luckily had to hand - and surreptitiously looking the car over the sergeant replied to The Principal's comment on the quietness of the road. He said,

'Lady, this is the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand and this is as busy as it gets.'

And turning to me he said, 'Now move along, mate, before you hold up a milk wagon.'

It was a most bizarre situation but then there are only 32,000 people living on the entire west coast of the South Island.

The Haast Kidnapping

A couple of days after our ‘run in with the fuzz’ a man abducted two women hitch-hiking on the West Coast. One had a knife held to her throat and the other suffered substantial injuries jumping from the car. The guy was eventually cornered on the lonely stretch of road between Haast village and Fox Glacier that we were to pass through a week later as night fell.

The next day we met a park ranger who had been involved in the manhunt who gave us more details of the drawn-out denoument. It turned out that the attacker was on parole and was later accused of murdering a woman in Christchurch before abducting the two tourists the same day. For his plea of guilty to all charges see here.

Reefton

We stopped in Reefton for a photo call. Train tracks, large earth-moving gear and a sawmill made me wonder what was going on there.

Reefton sits on the Stillwater-Greymouth branch of the Midland train line. The trains carry coal to the east coast and Greymouth. Reefton was once an important centre of the West Coast gold rush

(see my page West Coast Gold Rush).

Reefton Coal Mining

Francis Mining still produces coking coal from its Echo Mine in the Garvey Creek Coalfield near Reefton using truck and shovel methods. Screened onsite the coal is trucked to Reefton and from there by rail to the east coast port of Lyttelton and loaded onto vessels up to 65,000 metric tonnes and to Greymouuth on the west coast where vessels of only up to 8,000 metric tonnes can dock.

Birchfield Mining, a family owned firm, produces half a million tons a year of sub-bitumious coal from the Giles Creek Coalfield.

From Reefton the road climbs over a watershed and into the Grey River (Mawheranui) valley heading towards Greymouth and the Tasman Sea.

The Grey River

The particularly uninspired named of the Grey River and Greymouth comes not from the local weather but the prominent 19th century New Zealand politician, Sir George Grey. The Maori settlement at Greymouth was called Mawhera (‘wide spread river mouth’).

The valley opens out into rich farmland and for the first time in New Zealand I saw a field of maize which, given the wet oceanic climate, was probably being grown for ‘maizage’ (maize silage) for dairy cows.

We drove through the little settlements of Ahaura and Ngahere. There was a big sawmill at the latter.

Beyond Ngahere, at Donaldson Road, I could not but stop in order to take a picture of a skeletal looking steam locomotive (next page).

At the time we did not realize that opposite Ahaura on the north bank of the Grey River/Mawheranui there is a memorial to the Pike River Mine Disaster.

The Pike River Mine Disaster 2010

The Pike River Mine was controversial from the start as it was a drift mine that undercut the Paparoa National Park – which has a complete mining ban.

The opening of the 110m (360ft) ventilation shaft cut up from the 2.3km (1.4 mile) drift was only accessible by helicopter because roads could not be cut into the National Park. But the mine was a huge investment for the West Coast. Pike River Coal raised NZ$85m to invest in the mine once the initial plan had been approved in 1994. Plans were to export the good grade coking coal to international steelmakers.

The mine was opened in 2008 but production was slow to develop due to recruitment and technical difficulties (part of the ventilation shaft collapsed). In February 2010 with 150 full-time staff the mine exported its first 20,000 tonnes of premium coking coal to India.

Disaster struck on 19 November 2010.

A huge explosion left 27 people dead. Rescue workers could not enter the mine due to high levels of methane gas and on 24th November a second explosion occurred. The Chief Executive Officer of the mine announced that it was very unlikely if any of the miners were alive. Two more explosions followed.

Pike River Coal subsequently went into receivership, staff were laid off and the 27 bodies remained in the mine. In 2012 Solid Energy New Zealand completed its purchase of the assets of Pike River Coal in the hope of re-opening the mine.

In order to attempt this Solid Energy entered into an agreement with the Government setting out responsibilities around the recovery of the bodies and signed a Body Recovery Deed.

The 27 victims were a mix of New Zealanders, Australians, a Scot and naturalized Scot (Malcolm Cambell of St Andrews) and a South African. They varied in age from 17 to 62. A gallery of the miners can be seen below.

On 18th October 2013 work began to recover the Pike River Mine bodies. In December 2013 families of the victims began to receive some compensation. Prince William met families of the victims in 2011.

In May 2014 Peter Whittall, CEO at Pike River Mine at the time of the tragedy, returned home permanently to Australia. All charges against him were dropped in December 2013 due to a 'lack of witness availability' - too many witnesses were overseas in Australia and Crown lawyers did not have power to summon foreign witnesses.

Watch this dignified and condemning video from the New Zealand Herald which includes victims' families, and a UK mine inspector who castigates New Zealand health and safety and others.

Paul Maunder, of nearby Blackball, has written a book on 'Coal and the Coast' reflecting on the Pike River Disaster. It is available to listen to in chapters on Access Internet Radio, a NZ community resource.

There is a local and interesting blog entry trying to summarise the book (and its post-Marxist Badiouist theoretical slant) here that gives a flavour of the closeness of Coaster (West Coast) communities and their sense of embattlement and hope.

Interestingly it mentions that an activist miner's wife, Angela Balderson, from the Miners Strike in the UK (1984-5) now lives in the area. Her Brit husband, Trevor, is convenor of the miner's union at the Spring Creek Mine.

In late 2012 the Spring Creek Mine - which uses high-pressure water cannon (hydraulic monitors) to gouge out a seam that in places is 40m thick - was put into 'care and maintenance' by NZ State-owned miner, Solid Energy, as global coal prices fell (due presumably global recession and the falling price of US domestic (fracked) gas and the knock-on effect this has had on US and global coal prices).

New Zealand coal mining costs are impacted by difficult geology and compare unfavourably to the huge open-cast operations in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria in Australia. (Australia is the fourth-biggest producer of coal in the world after China, the US and India and the biggest global exporter of coal - mainly to Japan. In 2010/11 the industry produced 405 million tonnes.