II. Early days: from wool to refrigeration

The Grassland Revolution

The nation-building vision that drove New Zealand for much of its early and middle

pakeha history was that of turning its vastness into a' South Britain' of wool, lamb and dairy farming.

This was achieved with ruthless determination and heroic effort in a revolution that converted 51% of the country's surface area into grassland through bush clearance, the introduction of vigorous strains of exotic (European) grasses, the application of vast quantities of mineral and artificial fertilisers and herbicides and huge herds of sheep and dairy cattle bred out of British and Australian stock (King 2003, History of New Zealand p. 436-8).

This process was assiduously documented by some of the early gentleman pioneers such as H. Guthrie-Smith in his classic account of the Hawke's Bay sheeprun of Tutira (Tutira: the Story

of a New Zealand Sheep Station, 1921).

The early chapters of the book catch the excitement of young men taking on the great wilderness of New Zealand and living the good life. It was a precarious existence on vast tracts of land that were initially rented from Maori chieftains.

Stocking levels at Tutira were determined by the need to clear bracken in the spring and summer and when the winter months came stock suffered massive losses through malnutrition (for this see the instructive chapter on 'Fern-Crushing' pp.162-180 also known as 'mob-stocking' and 'stuff-and-starve' Te Ara: Rural Language).

Prior to refrigeration the whole enterprise and the back-breaking work of clearing and fencing the land was based on the international price of wool. Surplus sheep were sold off for pig feed or driven over cliffs.

Native vegetation was tenacious and the thin hill soils were infertile and unreceptive to British grasses. Credit was scarce and the early pioneers were thrown back on their own resources, pitiful cashflows and ability to bring in and manage labour to meet the peak demands of shearing and lambing whilst pushing forward the vast infrastructural works of clearance and fencing.

It was a huge adventure for the likes of the Guthrie Smiths, the Enys brothers at Castle Hill in Otago and the Barkers of Steventon near Christcurch. But without backing from a wealthy family for many it ended in bitter defeat.

Meanwhile, the great runs seemed in danger of producing the very aristocracy that so many had quit the UK to escape. And a new class of marginalised rural poor - 'the Cockatoos' of smallholders with 20 acre divisions of subsistence farming was emerging (see references in Lady Barker's Station Life in New Zealand and in Rose Tremain's novel, The Colour).

On the origins and uses of 'Cockatoo' see Te Ara:

New Zealand dairy farmers have long been known as cow-cockies, a term with Australian origins. Cocky is short for cockatoo, a name for a small farmer – and earlier for a convict.

The Ownership Revolution

Land reform and the development of refrigeration over long distances at the beginning of the 20th century changed all this.

Under the leadership of Prime Minister, John Seddon, the Liberal government began a process of breaking up the concentration of European land ownership in massive sheep runs where 1% of the landowners owned 64% of the land.

The policy broke up some 223 estates, which were fully compensated, and allowed the settlement of 7,000 farmers.

Spearheaded by John 'Honest Jock' McKenzie, a Gaelic-speaking Highlander who also crafted the 1892 Land Act that gave all New Zealanders access to rivers, forest and mountains, the process of land reform stopped with New Zealand's 'natives':

'Oddly, though [McKenzie's] first-hand memories of the Highland clearances did not prevent him from taking every opportunity to part North Island Maori from their land' (King, History of New Zealand, p. 272).

The Freezing Revolution

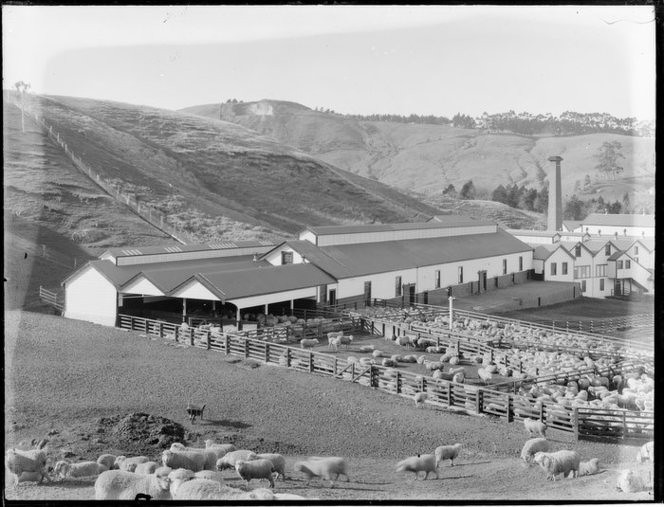

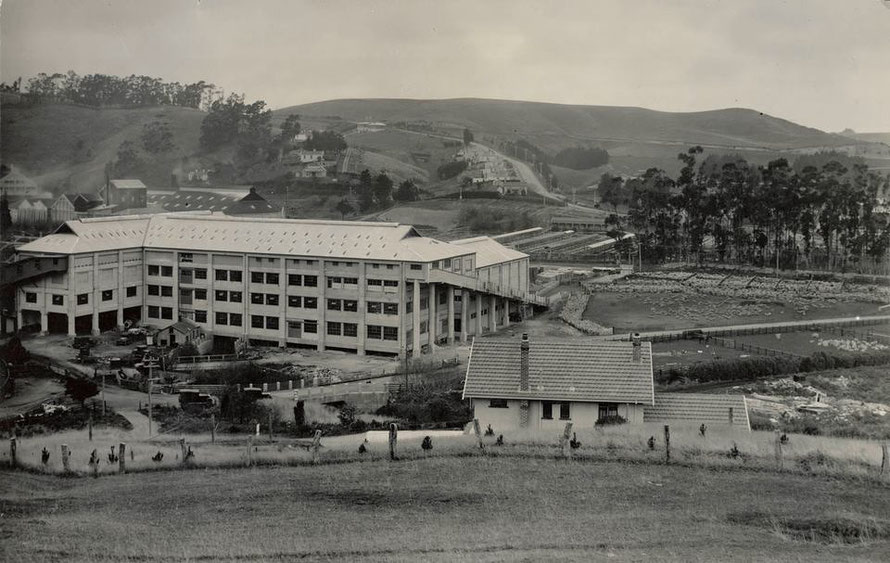

The first plant to freeze New Zealand lamb for transportation to the UK in 1882 was developed on the massive Totara Estate, on State Highway 1 8km south of Oamaru.

The estate, with 15,000 acres, was owned by the colossal Scottish-owned New Zealand and Australian Land Company.

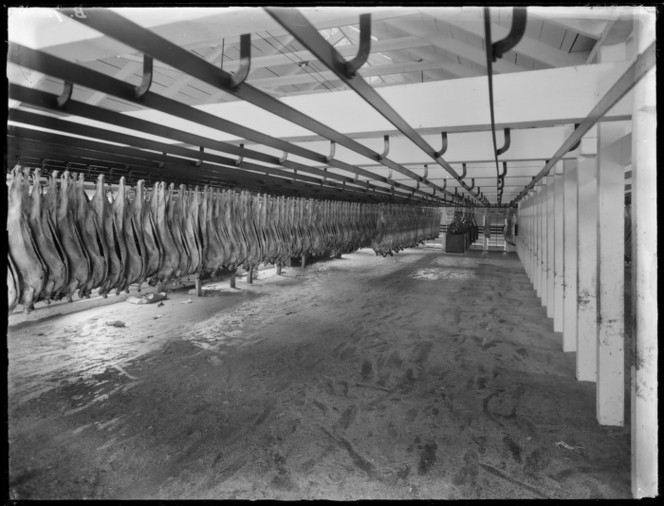

Previous to the advent of refrigeration sheep were kept on huge 'runs' and only the wool could be exported. This made farms completely dependent on global wool prices.

Old sheep were a real problem to dispose of - in Tutira: The Story of a New Zealand Sheep Station (1921) - they were sold at a pittance to a neighbour to feed to his pigs. In other places they were stunned and thrown into the sea.

The shift from vast extensive farms for wool allowed a smaller owner-occupier farming class to develop.

By 1902 frozen meat accounted for 20 per cent of New Zealand's exports.

Ironically, the area around Oamaru whre once sheep were dominant has gone over lock-stock-and-dry-milk-barrel to dairy farming.

Digger and Lynn McCullocha who farm at Glenavy are holdouts against the general trend and have recently been promoting their lamb in the US on a trip organised by an Oamaru company, Lean Meats Ltd.

Digger McCulloch is a third-generation farmer on the 284 hectare property which has 2000 ewes, 500 hoggets (yearling sheep - not little hogs as I at first thought) and 150 cattle.

The McCullochs are optimistic about the future of sheep and lamb in New Zealand. Numbers have declined and prices gone up as the migration to dairy got under way. And New Zealand is well placed to service the growing demand for meat in Asia.