Cyprus Mountains VIII: The Limassol foothills and wine-villages

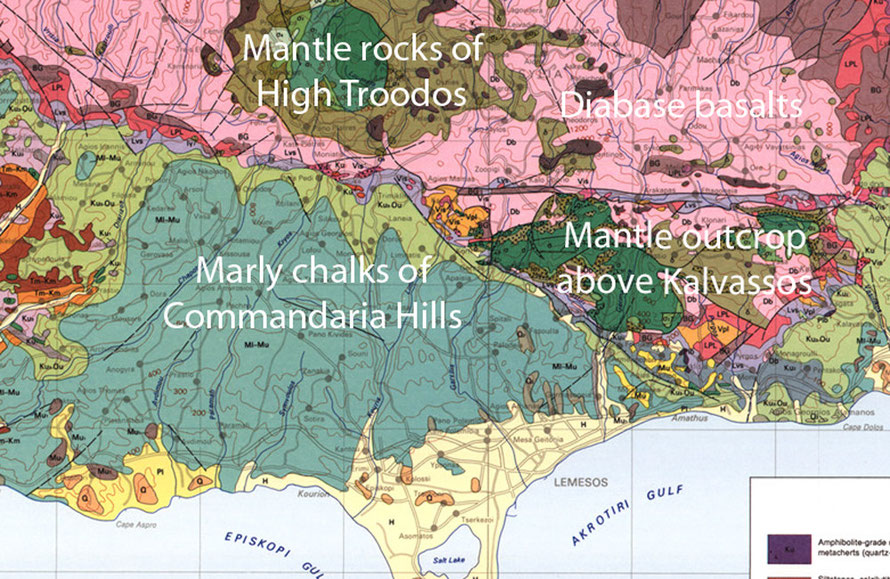

There is a remarkable change between the wine and non-winegrowing areas of the Pitsilia hills. This is due to the underlying rock that goes from the hard, infertile acidic diabase basalts of seafloor-spreading (90 million years ago) to the Middle Miocene (16-11 Ma) when carbonate sediments in deep- and then shallow-seas produced the the thick beds of alkaline marls and chalks of the Pakhna formation.

I was totally unaware of this as I was driving along, partly because I didn't know where I was really going and partly because I took a wrong turn that stopped me crossing the dramatic division between the two formations. I had been turned due south and downhill by the Pefkos junction and it was not until I started to climb back into the hills towards Alassa on the B8 and then Lofou on the F617 that I noticed how much the country had changed.

Gone were the scrubby, oppressive and endless chains of towering hills and close, steep-sided valleys. Instead the country opened out, the hills rising in spurs and broad swathes with a pronounced step-up to the High Troodos beyond.

I stopped at a petrol station to fuel-up and the guy told me they had had a few inches of snow on the ground yesterday - which was very unusual. It had all gone now and heartened by the road ahead I proceeded on my way.

It has taken me a while to get this but there is a crucial difference between talking about the Commandaria Hills/Region/Villages and the 'wine villages' in general.

The Commandaria villages are fourteen in number and concentrated in the east of the area of marly chalks and limestones in the Troodos foothills behind Limassol.

The Greek Cypriot term Krasochoria - 'wine-villages' - is more generic and refers to the broad band of wine-producing villages in the Troodos foothills of the Limassol district. The Commandaria Villages are a sub-set of the Krasochoria.

On the CTO Maps there is an area called the 'Koumandaria Region' and this covers broadly the area of the Commandaria Villages.

I am not the only one to be confused by this. Marc Dubin in the Rough Guide says that Malia is the 'highest of the Commandaria-producing villages' (p.130) but Malia is not one of the Commandaria villages. It may produce dessert wine but it cannot call this 'Commandaria' because it is not in the protected designation of origin (PDO) area registered with the EU, USA and Canada. Further, its KEO winery may store and bottle Commandaria but only if the grapes for this are first grown, dried and fermented in one of the named fourteen villages.

I'm glad I got that clear. I have plotted the 14 Commandaria Villages on the interactive map below.

The 14 Commandaria Wine Villages

So it comes as something of a surprise to me to realise that the only Commandaria village I went through was Kalo Chorio. And that had I continued on the road to Zoopigi - see previous page - I would have 'bagged' - so to speak, a second Commandaria village.

Indeed, my route - had it not been determined by a wrong turn at the Pefkos Junction - might look like a deliberate attempt to avoid the Commandaria villages. Anyway, such are the intricacies of other people's islands and of being abroad in general. At least now in retrospect the Commandaria Villages Wine Route sign that I saw in Kalo Chorio makes sense.

Cyprus Wines

So here are some notes on Cyprus wines in general and Commandaria in particular.

Cyprus wines and vineyards get a page (p.266) in Jancis Robinson and Hugh Johnson’s, The World Atlas of Wine (2001).

It says that the island has one of the ‘oldest winegrowing traditions in the world’ (Wikipedia site for Commandaria says back to 800BC) and was the first in the Eastern Mediterranean to ‘restore wine to the prime place in the economy it had before Muslim [ie Ottoman] invasion.

From the 1950s Cyprus exported huge quantities of ersatz sherries to Britain and extremely basic wines to Eastern Europe. The collapse of communism and changing tastes in the UK put an end to this trade and since the 1990s Cypriot ‘wine authorities have had to try and drag the island’s vineyards into the modern wine age.’

Winemaking is concentrated on the south side of the Troodos between 600m and 1,500m. The overwhelming majority of the island’s grapes are processed by four companies – KEO, ETKO, LOEL and SODAP – but smaller wineries nearer the vineyards are opning up. (For example, there are five in Koilani – see below).

Commandaria Wine

The most individual of Cyprus’ wines is the liquorous Commandaria that is made of raisined grapes and comes in red and white varieties. Apparently there is now a division between the production of Commandaria as a commercial dessert wine and the more prized ‘alarmingly concentrated wine of legend (it can have four times as much sugar as port) and can have ‘a remarkable haunting fresh grapeness.’

Cyprus vineyards have never suffered from the dreaded phylloxera and 70% of grapes for wine are grown from the indigenous Mavro (‘black’) grape.

Technique

The Commandaria villages are listed as Ayios georgios, Ayios Konstantinos, Ayios Mamas, Ayios Pavlos, Apsiou, Gerasa, Doros, Zoopigi, Kalo Chorio, Kapilio, Laneia, Louvaras, Monagri and Silikou.

Commandaria is made from a mix of the Mavro and white Xynisteri grapes and grown on four year plus vines at an altitude of 500-900m. These are grown to the

goblet (bush) method of vine-training and irrigation is prohibited. The picked grapes are sun-dried for a week (traditionally on the flat mud roofs of the Commandaria villages) and part-fermented

in situ in the 14 villages according to strict legislation. They can then be transferred to the big wineries where it is kept for two years in oak barrels and fortified to a maximum of 20%

alcohol.

In 2005 449,290 kilos of grapes were processed for Commandaria and 82,728 litres were exported (see Commandariawine.com).

Origins

During the crusades, Commandaria was served at Richard the Lionheart's 12th century wedding in Limassol to Berengaria of Navarre. He declared that Commandaria was, "the wine of kings and the king of wines". Despite this declaration, in 1191 he sold Cyprus to the Knights Templar, who then sold it to Guy de Lusignan.

However, the Knights Templar and subsequently the Knights Hospitaller kept a large feudal estate (covering 40 villages) head-quartered at Kolossi to themselves which was referred to as "La Grande Commanderie". The word 'Commanderie' referred to the military headquarters and the area under the control of the Knights became known as 'Commandaria' to raders and shippers.

When the knights started to produce growing quantities of wine for export and for the supply of pilgrims and crusaders en route to the holy lands the wine assumed the name of the region (see Wikipedia:Commandaria).

Anyway, all this confusion over wine areas and routes and villages and names was not on my mind as I drove up the spectacular spur of limestone that leads to Lofou. Deep valleys on either side cut away from the spur and these have been painstakingly terraced over the milennia with dry-stone walls of limestone.

It was cold again but the sky was a brilliant blue and the air clear and sharp. I stopped briefly in the deserted streets of Lofou, which sits tucked into a hollow on the bare spur. The narrow streets of limestone masonry almost sparkled in the sun.

Last vestiges of the previous day's snowfall were still evident in shady spots. I pressed on higher beyond the village, the road beginning to sway from side to side and roll up and down as the huge vista of the High Troodos and Mount Olympus revealed itself.

The wind was keraner now when I stopped to take photographs looking east to the Commandaria villages and west to the picturesque Krasochoria village of Koilani, tucked into the rising bulk of Mount Arames.

It seemed such a huge privilege to have the road, the sky, the wind, the views to myself. Nothing seemed to be moving but for a large bird of prey floating on the north-easterly breeze blowing up over the steep valley walls.

Up here there was definitiely a strong feeling of winter: drab colours, leafless trees, a starkness to the shadows enfolding the lee-side of the hills. But in the valley bottom of the Kryos ('cold') river flowing beneath Koilani there were signs of growth and verdant, vibrant meadows.

Looking north the great bulk of the high Troodos was snow-covered and startlingly clear in the limpid air. I could see higher settlements still - Kato Platres and Pano Platres and tucked below me Pero Pedi.

And the high peaks beyond the cloaking forests of Brutia and Black pine were spiked with the strange golf-balls and masts of military listening posts.

Koilani is another wine village that produces some good Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignons (Rough Guide, p.128). It is perched against the back of the Arames mountain above the Kryos ('cold') river, which had a good flow of water in it in January 2013 and on the map looks like one of the longest rivers in Cyprus, going from the foot of Mount Olympus to the sea to the south-east of the fantastic Roman settlement of Kourion (see my Kourion page). It is now damned at Kouris Reservoir.

I took a short-cut between the road from Lofou and the village rather than going to the head of the valley at Pero Pedi. This involved a precipitous rough road that cut under a crumbly soft limestone river-cut cliff. The road was scattered liberally with large clumps of limestone that had recently fallen. Clearly no-one had passed for some time in a car and I was obliged to clear a path. I stopped to take a photograph of the closed up eating-place under a huge plane tree on the river bank. As I was fiddling around I heard a mighty bang as a large stone fell off the cliff and onto the road where I had just been. I was lucky.

I drove up for a quick scout in the village, past some washed-out Christmas decorations. It was quiet and cold and the sun was getting lower in the sky.

According to the Wikipedia site, Koilani has preserved the rich, traditional folk architecture of the wine-producing villages:

Narrow, paved, ascending alleys, tiled roofs, picturesque upper floors, yard walls with earthenware jars, balconies, and arches with embossed frames at the entrances of houses that are built with regional, carved limestone.

Koilani's annual rainfall of 750mm allows the cultivatione of vines for wines and some raisins, and apple, pear, almond, olive, and citrus trees.

The village produces many grape-juice derived sweets: "khiofterka" (dry must jelly in rhomboid shape), "ppaluzes" (must jelly), "epsiman" (must molasses), "portos" (pulp with boiled must and wheat), "sousioukkos" (must-stick with almonds). The village is known for its aromatic "arkatena" (crunchy rusks with yeast).

The population peaked in 1946 at 1397 and is now around 280.

The village has a nice website and clearly there is a core of people trying to keep the village and its traditions alive, with football team, hunting club and help for the elderly. It says,

The urban pull phenomenon, beginning mainly during the 50's and continuing until today, has literally emptied the village.

We nostalgically remember life in the village, in the rough - but beloved - years when labour and diligence took away all impiety and selfishness from a person. Relationships were friendly and whole-hearted, entertainment was identified with the joy of the whole, and pain was common for all.

The pages on the different traditions of the Orthodox calender in these high mountain (820m) villages is very informative and touching.

I drive into Vouni having been promised 'a part-abandoned but highly picturesque' village by the 2009 edition of the Rough Guide (p.127) only to be confronted by a huge Aristo Developments sign. Aristo are quite canny in the way they provide 'facilities' whether these be bus shelters - see the Polis to Pomos road - or signage. It gives the impression of a benevolent and omnipotent company.

Vouni stands high on a spur between the Kryos and Chapotami valleys at an altitude of 800m. One of the main wine-making villages of the Commandaria (or Krasochoria - 'wine-villages', Vouni had a significant population of that rose to a peak in the 1946 census of 1,247. By 2001 this had fallen dramatically to 136 (see Vouni Village).

Only a half-hour drive from Limassol Vouni is high enough to escape some of the worst of the summer heat and is surrounded by the crumbling terraces and remaining vieyards of a once thriving village.

I drove on down the long spur of limestone and turned right at the bottom to quickly visit Malia.

Malia ( alternative Turkish Cypriot from 1958 Bağlarbaşı) was a mixed village from the Ottoman period and the biggest Turkish Cypriot village in the Commandaria. The population of the village increased throughout the British period, rising from 494 persons in 1891 to 712 in 1960. Turkish Cypriots always constituted the clear majority in the village and in 1960 made up 88% of the village’s population.

In January 1963 about 300 Turkish Cypriots from the nearby villages sought refuge in Malia. On 9 March 1964, following an attack by Greek Cypriot forces in which seven Turkish Cypriots were killed and many houses were damaged or burnt, approximately 1,000 Turkish Cypriots fled the village. They were scattered to the nearby villages. After 1968 many of the Malia Turkish Cypriots returned to their village, in part encouraged by the Republic of Cyprus 'because of the economic importance of the island’s wine industry and the fear that the large untended Turkish Cypriot vineyards would be destroyed'.

In 1974 the entire Turkish Cypriot population of Malia fled the village to the Akrotiri British Base Area where they stayed until February 1975, when they were transferred via Turkey to the northern part of the island. The total number of displaced Turkish Cypriots from Malia/Bağlarbaşı can be estimated to be 650-700 (624 in the 1960 census).

The population of the village in the 2001 census was 59.The Rough Guide (2009) reports that its houses are slowing 'being squatted and rennovated as weekend retreats' (p.129).

(See Prio: Malia/Bağlarbaşı.)

By now I was feeling fatigued behind the wheel. My legs aching. My stomach empty. I'd been going without a real break since breakfast. But I still felt I could squeeze a bit more Cyprus in before darkness threatened and I needed to turn tail for Nicosia.

After getting by an irritatingly slow car I made good time swooping down the hills shadowing the course of the Kryos until I crossed its wide, dry-looking bed before turning east in the growing Limassol traffic for Kolossi and Akrotiri.