Mountains (8 pages)

I. The Troodos Massif

There are two ranges of mountains in Cyprus - the Troodos Massif in centre and west of the island, and the Pentadaktylos or Kyrenian Hills that run along the north coast reaching a maximum height of 935m and peter-out on the Karpasian Peninsula. Thus far I have only explored the Troodos Massif in the south of the divided island. I hope to see more of the Kyrenian Hills than views of them across the Green Line at some time in the future.

Geography: Troodos Massif

The central part of the Troodos Massif has an area of approximately 3,500 km² (38%) of the island’s total land area of 9,252 km² and rises in the west to nearly 1952m at Mount Olympia.

In the north the Troodos massif is organized into a series of north flowing valleys that cut down through the mountains that rise up as a rampart from the northern plains. These valleys include the Xeros, Marathasa and Solea. Further east the valleys are less pronounced but a series of northward flowing rivers run out of the north-eastern Troodos – the Elaia, Peristerona, Akaki, and the ? that flows down into Nicosia.

In the north west the Tilliria mountain spurs run down to the coast, between Pomos and Kato Pyrgos with steep valleys cut by shorter streams, - the Limnitis, Pyrgos and Livadi - rendering east-west travel difficult.

The eastern Troodos rise up into the great wall of Mount Kionia (1420m) above Machairas Monastery and then fall away to the east in a series of spurs and strange eroded flatlands between Tseri and Dali rising up again at the outlier on which Stavrovouni perches and gradually coming to a merging halt in the low marl hills that lie in an arc behind Larnaca Bay and stretch out north westwards through Atheniou and onward almost to Nicosia.

The southern Troodos are less steep and consistent than the northern side. The gradient to the sea is less predictable or rather there is a strange kind of jumbled high plateau land cut by rivers and valleys that to seemed to me – travelling across it from south-east to north-west - to have little sense of natural order or orientation. The order of the river valleys of the Pentaschoinos, Vasilikos, Germasogeia, Garylis, Limnatis and Kryos (that flows into the Kouris) seems to get lost or peters out in the Pitsilia and eastern Commandaria Hills. Further to the north west beyond Petra tou Romiou the river valleys become more pronounced and straighter with the Diarizos, Xeros and Ezousa valleys that run south-west to the sea before Paphos.

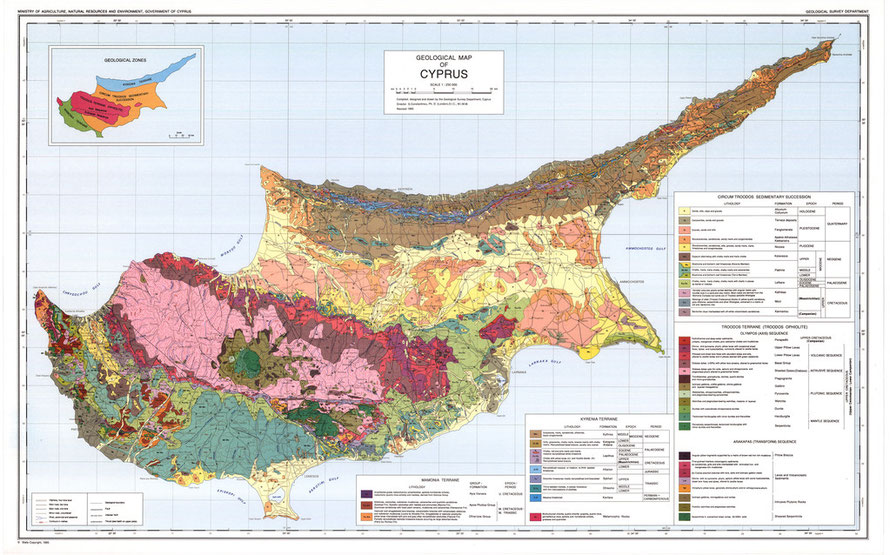

Geology: The Troodos Ophiolite Complex

The Troodos Ophiolite Complex (TOC) was (formed in the Upper Cretaceous ('creta' - Latin for 'chalk') period (90 million years ago (MYA) on the Tethys sea floor, which then extended from the Pyrenees through the Alps to the Himalayas.

An ophiolite is a fragment of a fully developed oceanic crust, consisting of plutonic, intrusive and volcanic rocks and chemical sediments.

The TOC was created during the complex process of sea-floor spreading and formation of oceanic crust and became the Troodos mountains through the collision of the Eurasian and African tectonic plates.

In this process the piece of ocean crust comprising the TOC has been turned upside down so that the older layers of rock in it sit above the younger ones. This inversion arose from the way the ophiolite was uplifted (diapirically) and later eroded. The uplift of the island took place during episodes of abrupt uplift up to the Pleistocene (2 Ma).

The TOC has been vital for the formation of the minerals upon which the island's wealth depended from antiquity to recent times.

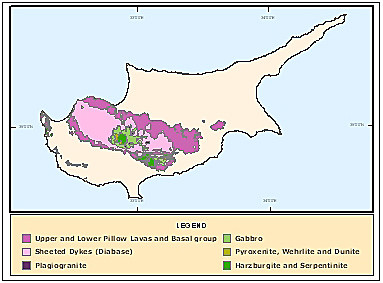

The upside down order of the rocks in the ophiolite goes something like this - from the oldest and deepest (formed in the Earth's mantle - the bit between the molten core and the exposed layers of igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rock) to the huge younger seafloor lava flows.

At the top of the Troodos the mantle rocks are mainly composed of harzburgite and dunite with 50-80% of the original minerals altered to serpentine, and serpentinite (with or without concentrations of asbestos). These are the oldest rocks.

Then come the cumulate rocks which include dunite with or without chromite concentrations, wehrlite, pyroxenite, gabbro and plagiogranites, which are observed in small discontinued occurrences.

Following the mantle-related rocks comes the igneous (fire) rocks laid down by the seafloor-spreading of liquid magma as sheeted dykes and two series of pillow lavas and lava flows, mainly of basaltic composition.

The massive ore deposits of the TOC consist of sulphides (formed in lavas - copper), chromite formed in dunite and asbestos (formed in harzburgite) mineral deposits.

The exposure of the ore bodies to the surface, and especially that of massive sulphides and amiantos, resulted in the discovery and exploitation of copper since antiquity.

The Troodos Ophiolite has a very significant role for the water budget of the island. Most of the rocks, especially the gabbros and the sheeted dykes are good aquifers due to fracturing.

For the above see Cyprus Geological Survey Department