Cyprus Interiors II: The Mesaoria

Introduction

I have really struggled to make this page. Maybe it reflects something of the elusiveness of the Mesaoria. Almost by definition it is the bit that is not defined, or only defined by other boundaries: the sea, the mountains and the urban/suburban landscape.

The 'plain between the mountains' sounds so simple and straightforward but as soon as it is defined the Mesaoria escapes its definition. Some of it is not between the mountains. And some of it is not what would normally be defined as a 'plain'.

It is in many ways a harsh, finely textured landscape that belies its apparent uniformity at nearly every turn. And because it is divided by the Green Line and the Buffer Zone it is not easily accessible. I have looked down on the Morphou Plain from an incoming flight and from the hills of the Xeros Valley but I have not been there. Similarly, I have yet to experience what might be called the 'Mesaoria proper' bounded by Famagusta, Nicosia and the Kyrenian Mountains.

For the tourist, the Mesaoria is that blank space you drive through to get somewhere else: sweltering hot, dusty, windswept and studded with army and UNFICYP posts and bases.

Even in ancient times kingdoms and settlements skirted around its seaward and mountainous edges (Salamis, Tamassos, Kition, Solloii) - the exceptions being the kingdom of Idalion and sanctuaries of Golgoi-Ayios Photios, Atheniou-Malloura and Potomia. Later, under the Venetians, the capital moved to Nicosia plumb in the middle of the plain to afford greater protection from sea-borne invasion.

Definition

The Mesaoria - literally 'between the mountains' - is the plain of flat alluvial soils, shallow river valleys and low-lying hills that lies between the Troodos mountains in the south and the Kyrenian mountains in the north of Cyprus.

In effect, the Mesaoria runs from Morphou Bay in the west, through Nicosia to Famagusta and pretty much around to Larnaka. I use the 400m contour as the upper limit of the Mesoria - others have used the 1000ft contour (see my Locusts page). Much of this area is now to the north of the Green Line.

The Mesaoria: Geology, Soils and Land-use

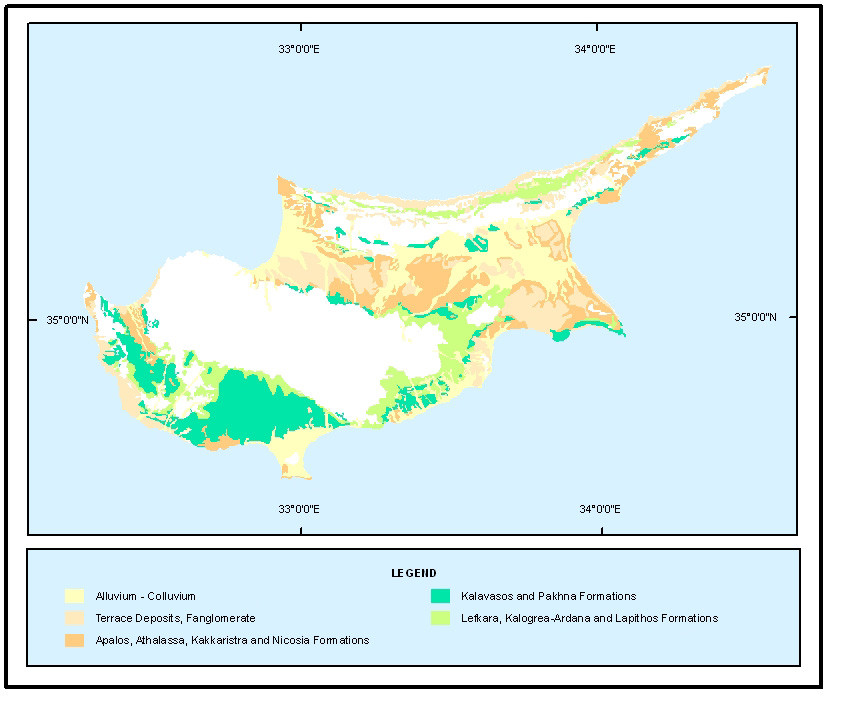

Geologically-speaking the Mesoria is part of the the Circum Troodos Sedimentary Succession. It is made up of alluvium, terrace deposits (Fanglomerate) and the Apaios, Athalassa, Kakkaristra and Nicosia Formations.

The Cyprus Geological Survey Department website puts it like this:

With the re-connection of the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean, a new cycle of sedimentation began (Pliocene, 5 million years ago). The Nicosia Formation was deposited first and contains siltstones (grey and yellow) and layers of calcarenites, marls and calcarenites interlayered with sandy marls. Finally, the Fanglomerate is a Pleistocene formation and includes clastic deposits (gravels, sand and silt).

'Clasts' is a geological term that means 'rock fragments'. If they are water-worn (and thus rounded) and larger than sand particles (over 2mm) they form 'conglomerates' when mixed with sands, clays etc. If the clasts are angular they form 'breccias'. The size of the clasts goes from 'granule' to 'pebble' to 'cobble' to 'boulder'.

A fanglomerate is defined as the accumulation of series of conglomerates into an alluvial fan. In rapidly eroding (e.g. desert) environments, the resulting rock unit is often called a fanglomerate' (Wikipedia: Conglomerates).

These fanglomerates were formed by the erosion - unroofing- of the Troodos Ophiolote Complex (see Mountains) and the alluvial transportation of clasts, sands and silts. On the north Troodos border these are between 12m and 90m thick and were fed by rivers flowing in a radial pattern off the Troodos Massif as either streamflood or sheetflood processes. The ones in the south east - behind Larnaka Bay - are only a few metres thick and were again formed by northward and then eastward flowing rivers carrying weathered material down from the Troodos Massif.

These deposits are made up of three distinctive layers/types which contribute to the interspersed and eroded table-like layers - that can look to the untrained eye (ie mine) as being man-made - so characteristic of the higher areas of the Mesoria (see my photographs below of the area around Tseri.) (For the geology of the Cyprus fanglomerates see Poole, A.and Robinson. A., 1998, Pleistocene Fanglomerate Depositition Related to the Uplift of the Troodos Ophiolite, here).

The fanglomerates are vital for water resources on Cyprus,

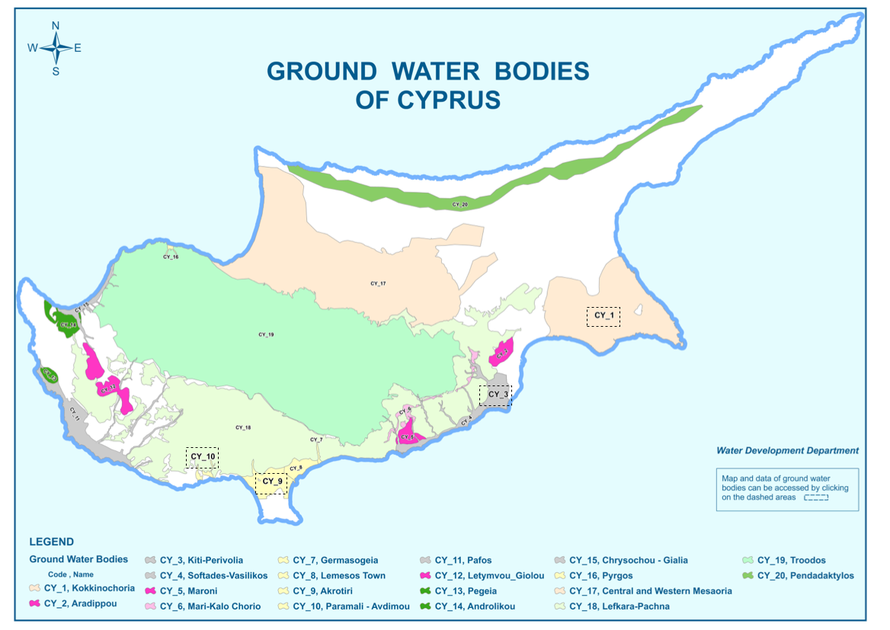

The clastic sediments are the most important aquifers of the island. These are mostly developed in broad valleys and river deltas. Such aquifers are those of western and eastern Mesaoria, Akrotiri and Pafos. Aquifers are also developed in porous rocks such as calcarenites, in limestones and gypsum that are characterised by karst, and in fractured rocks such as chalks, limestones, etc. (Cyprus Geological Survey Department).

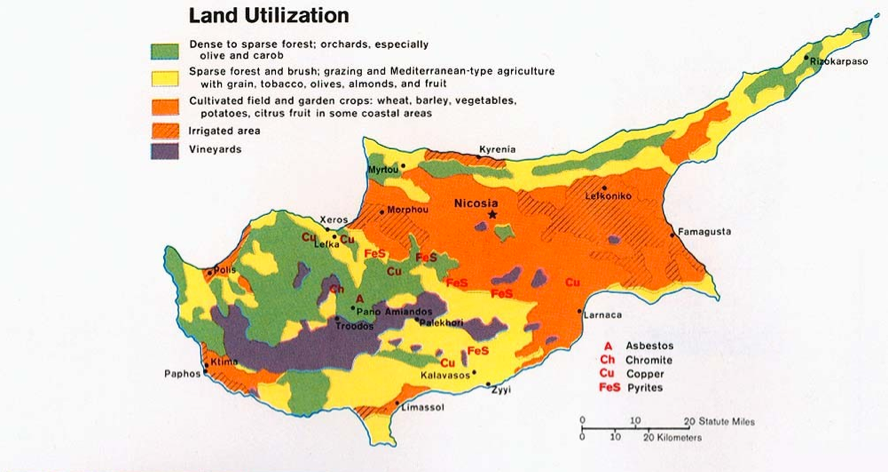

The soils of the Mesaoria are as follows: red soils and alluvial soils predominate in the Morphou-Nicosia area with the bigger areas of alluvial soils around Morphou (which support intensive citrus farming).

Large areas of alluvial soils were laid down in the triangle between Nicosia, Famagusta and the meeting of Famagusta Bay and the Kyrenian mountains.

Terra rossa soils are found south of Famagusta to Cape Greko and eastwards giving way to brown earths and raw calcareous soils in the hills between Larnaka and Nicosia (see EUsoils).

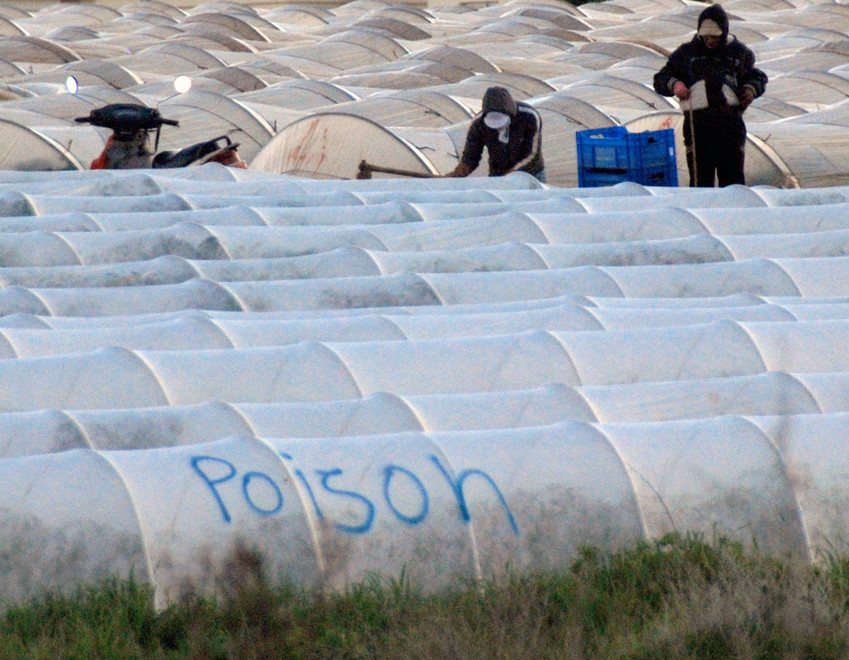

The Mesaoria has traditionally been the grain basket of Cyprus. Potatoes are also grown - traditionally in the terra rossa soils to the south of Famagusta (in the so-called Kokkinakhoria - 'red-villages'). And there is a lot of onion growing on the road west from Nicosia to Peristerona and mixed citurs and olive groves below Peristerona (see my Peristerona page).

The Mesaoria: Water

The agricultural productivity of the Mesaoria with its varied soils and geomorphology is absolutely determined by rainfall and access to water resources.

Most of the cultivated land in Cyprus (around 185,000ha) is planted with rain-fed temporary crops (cereals, food and feed legumes, green fodder and industrial crops) in the plains.

The area of irrigated land planted with fruit trees, grapes, vegetables, potatoes etc. varies from year to year according the water availability from 30 000 to 40 000ha. That is about 19% of the total cultivated land.

Agricultural land in Cyprus is privately owned and nearly all farms are small family enterprises. The mean size of holdings is 4.5ha - ranging from 2.7ha in the mountains to 5.6ha in the hilly vines and the plains. These holdings are themselves fragmented between separate parcels of little more than half a hectare located in one or more villages. The total number of small-holders in Cyprus is approximately 42,500.

The uneven distribution of the island's rainfall is two-fold. Firstly, most rain falls in the winter and, secondly, most rain falls on the mountains. The Mesaoria itself receives very little rain - 250-300 mm a year - and this meagre supply is increasingly threatened by a gradual reduction and periodic drought.

The Troodos and Kyrenia massifs act as giant rainmakers and without them Cyprus would be a semi-desert. The link between the intensively cultivated plains and the mountains are the rivers that transport the water from the mountains and the lowland aquifers that are charged by these rivers. A map of the main aquifers is presented below.

Agriculture accounts for 75% of water consumption in Cyprus the majority of which comes from government dams and private boreholes. A recent study of groundwater resources concluded,

‘During the last decade almost all aquifers exhibit trends of depletion ... Frequent droughts have reduced direct and indirect groundwater recharge and construction of dams has resulted in reduced recharge in downstream aquifers. [And in many cases led to almost complete elimination of the natural riverbed recharge of aquifers p.13.] At the same time farmers … have continued extracting the same quantities of groundwater and in most cases have increased these quantities. p.9’

‘The most common water quality problem in Cyprus is the contamination of groundwater caused by seawater intrusion. The coastal zones of the major aquifers in Cyprus e.g. Kokkinichoria, Kiti-Perivolia, Akrotiri Morfou etc. have been abandoned because of this phenomenon. Intensive agriculture and excessive use of fertilisers resulted in nitrate pollution in may aquifers’ pp. 9-15 in (D. Argyropoulos, D. (2004) Volume 5: Initial Characterisation of Groundwater Bodies, Implementation of Articles 5 & 6 of the Water Framework Directive 2000/6/EC Ministry of ANR&E).

Seawater intrusion destroyed the coastal portion of the Famagusta aquifer with serious losses to the citrus industry and the same process had begun noticeably near Limassol and Morphou. In the

Western part of the island, where 73% of the island’s citrus plantations existed (the Morphou Triangle) groundwater levels were as much as 3 meters below sea level and sea water was already

causing salinization of wells (see Phocaides below).

Argyropoulos (2004) above called for immediate action to reduce depletion of inland aquifers by the drastic reduction of extraction and by artificial recharge. Without this ‘life-giving aquifers will be lost to many future generations p.15.’

Much is being done to avert a crisis through government intervention to control groundwater pumping and intensive efforts to improve the efficiency of irrigation techniques and technologies (see Phocaides, A. (2002) Irrigation Advisory Services in Cyprus).

But as the head of the environmental NGO, Terra Cypria says, the official policy of water conservation can appear expendable when other, perhaps more powerful, goals come into play,

“For example, there was a political decision to develop 14 golf courses. Around the golf courses there will be villas, there will be hotels, condominiums, restaurants, swimming pools. That’s a use of water [and] we’re sure it’s not a good decision. Desertification ... is the biggest problem we are going to face in the next few decades. What we can do is start taking steps now to ameliorate the problem, or to make sure that we adapt to it.”

He believes that Cyprus will face a real threat of desertification over the next few decades (see the Euronews video on water resources in Cyprus here).

One system for recharging depleted aquifers is that of using waste water via deep boreholes. For proposals for a pilot scheme in the Liopetri area using waste water from the Water Treatment plant at Agia Napa see Voudourisemail, K., (2011) Artificial Recharge via Boreholes Using Treated Wastewater: Possibilities and Prospects, Water 3(4).

Interestingly Voudourisemail found high levels of cyanides and oil, grease and fat in the treated water from the Agia Napa plant due to illegal dumping of industrial waste water and the absence of a fat separator at the plant.

Also see here my page on Water Resources.

Despite being something of a big dusty plain the Mesaoria is surprisingly varied.

It has not been massively developed and feels very different from the coastal littoral with its endless villa developments. Population and social flight from the land, agriculture and the village as the centre of social and political life has also had its impact. Added to this of course is also the trauma and displacement of the island's post-war history.

The different areas of the Mesoria also change dramatically between the seasons. In June the cereal harvest is already underway and the fields then lie bare under the sun for months. But in January and February they are stunningly green with new wheat and barley growth.

The different faces of the Mesaoria: photographs from Morphou Bay to Paralimni

For different views and aspects of the Mesoria see my pages on Peristerona village, water resources and locusts.

To Interiors II: Wheat and Carob Country