XII. Buying and selling Cyprus' past

Introduction

Rarely in the history of modern civilised nations could a British man of letters become acquainted with such an extraordinary phenomenon of despoiling the cultural heritage of one's own homeland.

Kyriacos, D., Victorian Cyprus: society and institutions in the aftermath of the Anglo-Turkish convention, 1878-1891 p.20

The despoiling of Cyprus' cultural heritage was in many ways a process driven forward by the avarice and ambition of 19th and 20th century collectors/entrepreneurs/archeologists.

The local population were often happy to provide either the labour or the artifacts these collector-entrepreneurs competed to collect and ship to back to admiring audiences and institutions in London, Paris, Berlin and New York.

Rendered into a state of indigence by the high taxation and complete neglect of the Ottoman authorities the 19th century Cypriot peasantry were desperate for any source of cash or in-kind income. The early collectors exploited this want shamefully for their own aggrandizement, personal reward and position.

Kyriacos (above) recounts the methods 'Louis' (Luigi) Palma de Cesnola (for more see below) employed to secure the fruits of his excavations:

When Cesnola noticed that some of his peasant employees concealed objects found during the diggings he contemplated the following stratagem: He laid upon a chair a book with engravings resembling objects he knew one of them had concealed, and told him that this book was divine, and that it could tell him whether something had been hidden. Then he showed him the engraving. 'The amazed and convicted peasant would clap his hand on his head, or use some sign of astonishment ... "he had a book telling him everything!" ... In this way I got possession of everything that 'had been found, without much annoyance' (p.19-20).

The History of the of Cyprus Museum

The history of the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia is a fascinating glimpse into British rule in Cyprus (1878-1960) and the strange disjuncture between the project of the competing western imperial powers to justify their empires by the assiduous uncovering, collection and historicisation of Ancient Greek and Roman Civilizations and the imperial treatment of the relics of those civilizations.

A first catalogue of the Museum’s collection was begun in 1892 – 14 years after the British had assumed control of the island in 1878 - and finally published in 1899. It was written by John Myres, an Oxford academic and Max Ohnefalsch-Richter, an archeologist and supervisor of antiquities for the British authorities.

The catalogue states: The Government Collection of Antiquities has come into existence in virtue of the Ottoman Law of 1874, which still prevails in Cyprus; and by which the Government acquires a third part of the finds in any excavations which are permitted. Needless to say, the surreptitious excavations which are persistently carried on by all classes in Cyprus pay no such tribute, except in the rare cases when antiquities are confiscated. (p. v-vi)

The British Government of Cyprus has hitherto spent nothing in maintaining, or even in properly storing the Collections for which it is responsible. Many of them lay for years in the outhouses of the Commissioner’s Office in Nicosia, exposed to all kinds of ill usage. The unique colossal statue of terracotta, CM. 6016, and the fine engraved silver bowl, C. M. 4881, were found here in 1894 irreparably damaged, and a number of other objects have not reappeared at all. The statues from Voni, also, long stood in the open corridor of the Government Offices, and suffered serious damage. The Government share of the results from Kurion, 1895, is still lying in cases at Nicosia.’

The Museum, in which the Government Collections are now mainly housed, was established in 1883, and is maintained wholly by private subscriptions. … Subscriptions, however, soon fell off, and in 1894 the funds of the Museum were almost exhausted.’

Labels and fragmentary lists testify that attempts have been made from time to time to rearrange the Collections. … Irreparable damage was done when part of the Collection was sent, along with Col. Warren’s exhibit, to the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1887; and, again, some time between 1889 and 1894, by the dispersal of the Tomb Groups excavated for Dr. Dlimmler in 1885, and by a 'sale of duplicates‘ by which a number of specimens of scientific value passed into private possession.’

Even in the Museum, the condition of the Collection was in 1894 deplorable. The large sculptures, inscriptions, and architectural fragments lay indiscriminately in the courtyard, some exposed to the weather, and all to frequent injury; a large number of Attic vases were discovered, after the Catalogue was already written out, in the wardrobe of the caretaker’s wife; and other collections continually came to light, as it became possible to empty and search one outhouse after another.

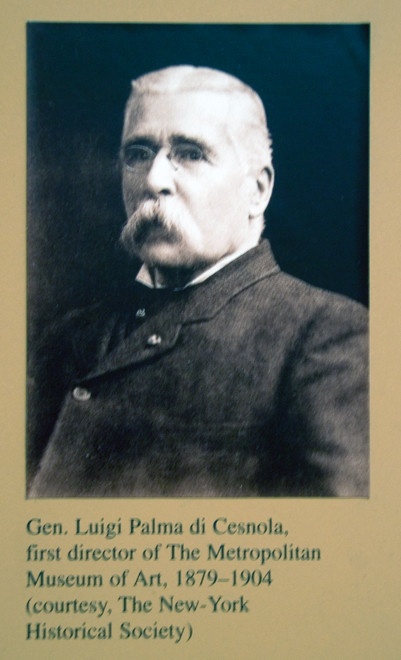

Much concern had been caused by the activities of Luigi Palma di Cesnola, a member of an exiled Italian noble family who had become a US citizen.

The Government inspection of excavations is in many cases conducted by untrained persons, whose inventories even when they are intelligible at all, are valueless for the identification of the objects which are described. Consequently a large part of the Government Collection has lost almost all scientific value. It would be well if future excavators were obliged to deposit a copy of their own inventory of the share which they leave behind. (p. vi-vii)

(The digitalized copy of the catalogue is from the library of Einar Gjerstad (1897 – 1988), who headed up the huge and important Swedish Cyprus Expedition. There is a street named after him in Larnaca.)

Tomb robber extraordinaire: Luigi Palma de Cesnola

Vasso Karogeorghis, a leading authority on Cypriot antiquity writes,

During the years of Turkish [Ottoman] rule there was no attempt at protecting antiquities. Thus the Italian diplomat [sic - he was briefly a US consul] L. Palma di Cesnola was able to act freely in amassing a huge collection of priceless ancient objects excavated by organised teams of tomb-robbers working all over Cyprus.

(V. Karageorghis, The Cyprus Museum, Nicosia 1989 p.6)

This story was told in the Cyprus Mail in more lurid detail:

The first phase [of the expropriation of Cypriot antiquities] consisted of the period of Luigi Palma di Cesnola’s activity in Cyprus from 1865-1875. Palma de Cesnola, an amateur archaeologist, pillaged a number of unexcavated sites and collected over 35,000 objects without the permission of the Ottoman authorities.

When the Ottomans heard that he intended to ship the relics to the US to sell them to the newly opened Metropolitan Museum they prohibited the export. Palma di Cesnola nevertheless quickly loaded a number of boats, which set off for the US. Five thousand pieces were lost in a shipwreck while countless others were smashed to bits on the rough sea passage.

His bandit act did not ruin his reputation or career. In 1879 he was appointed Director of the Metropolitan Museum. Today the Cypriot collection at the Met – the most comprehensive in the Western Hemisphere – is called the Cesnola Collection (see Constantine Markides Taking stock of our stolen past August 13, 2006, Cyprus Mail.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York puts a rather different spin on this. It stresses Luigi Cesnola’s status as US Consul, a post that was quickly cut due to US Federal austerity measures. According to the Met, during his time as US Consul,

'[Cesnola] amassed an unrivalled collection of Cypriot antiquities through extensive excavations and by purchase. The whole enterprise was funded from his own resources….soon afterward, Cesnola shipped the collection to London … It was at this point that the newly founded Metropolitan Museum of Art intervened and acquired the bulk of the collection … [Luigi] Cesnola accompanied his collection back to New York … In 1877, he accepted a place on the Museum's board of trustees and served as its first director from 1879 until his death in 1904'.

The acquisition of the collection was a major coup for the Museum and helped to place it and parvenu New York on a cultural par with its European rivals.

When the Metropolitan Museum opened at its current site in Central Park in 1880, the collection was the focus of attention, heralded as a great asset to the city of New York, which was then aspiring to become a major cultural as well as business center. The richness and fame of the Cesnola Collection also did much to establish the Museum's reputation as a major repository of classical antiquities and put it on a par with the foremost museums in Europe (see The Cesnola Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

The pillage of Cyprus antiquities was in part stopped by the arrival of the British in 1878. But rather than protecting the great store of antiquities British rule helped British museums. The British Museum itself has a substantial collection of Cypriot antiquities and these were much enriched by the sponsoring expeditions to Cyprus between 1890 and 1896.

Tatton-Brown's excellent, Ancient Cyprus, (British Museum, 1997) makes no mention of the way in which the British Museum collection was acquired. A search of the on-line museum collection shows 261 items related to E H Lawrence, 377 related items to Luigi Cesnola, and just 8 items for Alessandro Cesnola (see also my Kourion page which details excavations at this site and the activities of the British Museum).

In 1905, the first ‘antiquities law’ in Cyprus was enacted and the Cyprus Museum acquired a semi-official status. A Governing Committee became responsible for determining which archaeological finds were indispensable for the Museum’s collections and that therefore were to remain in Cyprus.

A second antiquities law was passed in 1935 and the museum acquired complete official status under the Department of Antiquities. The huge task of cataloguing a rapidly expanding range of artifacts was disrupted by the II World War, when the stock was removed to a new site for safety (Karageoghis 1998 op cit. p.6).

The partition of Cyprus in 1974 has again hindered the extent of possible excavations, particularly at Salamis, and gave rise to a new wave of desecration and looting of Byzantine treasures in the Turkish-army occupied North. Mosques in the south of the island were also attacked and desecrated by Greek Cypriots.

(For an important discussion of antiquity law in Cyprus see Hardy, S.A. Cypriot antiquities law on looted artefacts and private collections. See also Hardy, S.A. 2009: The liberation of censorship in Cypriot archaeology on the suppression of information concerning the destruction of Islamic religious sites in the Republic of Cyprus. See also E. Goring, A Mischievous Pastime: Diggings in Cyprus in the Nineteenth Century, Edinburgh 1988).

There is a fierce argument in the museum and broader cultural policy world regarding the repatriation of ancient and not-so-ancient artefacts.

On the 'keep them in the big Western museum' side is James Cuno, who argues in Who Owns Antiquity: Museums and the Battle over our Ancient Heritage, (Princeton University Press, 2008) that the great encyclopaedic museums are an important counter to the national identity politics that attempt to retain and politicise artefacts and antiquity for particular national ends.

He says,

Antiquities are the cultural property of all humankind and evidence of the world's ancient past and not that of a particular modern nation. They comprise antiquity, and antiquity knows no borders.

Cuno is director of the Art Institute of Chicago and his thesis is challenging but one has also to acknowledge the looting and expropriation of Greece, Turkey, Cyprus etc by the 'Western Powers' for 'particular national ends' and 'identity politics'.

This project has often been couched in much more high-minded language than that of 'national identity politics' but is that not what it really was? And to a greater or lesser extent continues to be despite the fine words?