IX. The Locust Problem in Cyprus: over and out?

Jennings (1988) suggests that desert locusts became an, at least recorded, issue In Cyprus from the middle of the 14th century when huge plagues of them caused havoc and were believed to have arrived from North Africa. In 1409-12 a terrible plague did much damage.

Cycles of plague usually lasted for several consecutive years. Peasants were ordered to collect and bury locusts and their eggs in large pits. When locust plagues coincided with drought the island was devastated.

In the 15th century it was believed there was a special or holy water (from Persia – hence ‘Persia water’) and birds ‘water birds’ or ‘birds of Muhammad’ that could be attracted to deal with the locusts. These avian destructive powers were later attributed to the Russet Starling (Pastor roseus) ‘the extinguisher of the wandering locust’ by the Ottomans and which is still believed to foreshadow locust swarms by Armenians and Tartars (Jennings, p.306).

In 1510 vast quantities of wheat had to be imported to Cyprus from Syria ‘solely due to the great voraciousness of infinite numbers of locusts – cavalette – [zuuor in Turkish] which covered the island like snow’ says Jennings, paraphrasing his Venetian source (Jennings p.284).

1577 Ulrich Krafft, a seaman enslaved by Muslims, gives an accurate report on the locust problem in Cyprus (Jennings p.289) which had suffered terrible plagues in the previous 5 years. He described their life cycle: they emerge from the ground in early March, crawl over the earth in vast quantities consuming all green things to the root and back to the dead wood until 23 April when they grow wings and swarm in huge flocks blotting out the sun. In the last days of June they lay eggs in the ground and die leaving behind a terrible stench.

A report in 1750 told of the plight of the people of Poli di Chrisofou (Polis tis Chrysokou),

‘The misery of the people is at present inconceivable, occasioned by a total want of rain … what little [vegetation] did appear above ground, was in many places totally destroyed by innumerable swarms of locusts…which destroyed everything that had the least verdure, so suddenly, as to have destroyed in one night, a field which would have given bread to fifty thousand men for a week beside fodder for the cattle’ (Jennings, p.293).

Under the Ottomans strenuous efforts were made to contain the problem through the collection of eggs, particularly under Osman Pasha in the mid-nineteenth century.

In 1880 under British administration the Island Treasury advanced £27,250 to fund a ‘vigorous campaign in the hope of ridding the island altogether of the scourge’ (Orr p.143) of the common locust (Stauronotus cruciatus) and Moroccan locust (Dociostaurus maroccanus) - which were smaller than the desert locust - through the collection and purchase of eggs and live locusts and construction of traps.

In 1880 all Cypriots were obliged to gather 8 oke (1 oke = 2.8 lbs. Eight oke = 8.4lbs/3.8kg) of locust eggs. That year a massive total of 189,000 oke (236 tons) of eggs was collected and destroyed.

In 1881, 2,631 trappers were employed to trap the locusts before they reached the flying stage. Jennings reports that 195 billion locusts were killed in 1883 and 56 billion in 1884 (pp. 305-6).

In 1881 the Locust Tax was imposed by the British administration. It was charged at an equivalent of 1% of the annual value of tithe-able produce, property income or trade profits (Orr p.90). In 1897 it was used to establish a Public Loan Fund for credit to small agricultural producers.

The locust problem, however, continued to absorb considerable resources (£5,000 a year) and in 1948 cost the administration £21,000. By this time DDT was being used in huge quantities to attack the locust problem causing immense damage to the wildlife of Cyprus - some say it has never recovered from the trauma - see Thoughts of Cyprus and Malta 5 March 2013).

The Anti-Locust Research Centre conducted in-depth research on the habits of the Moroccan Locust in Cyprus in the late 1940s and concluded,

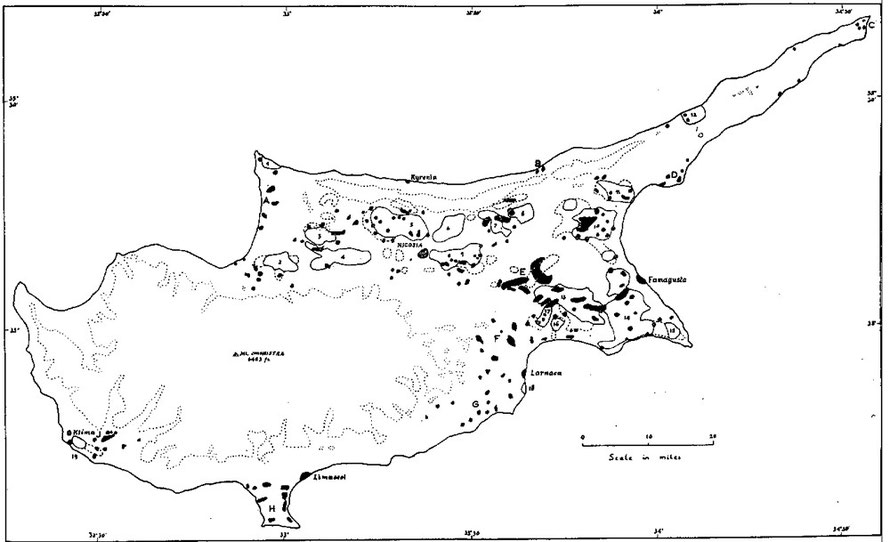

‘the main areas of reproduction of the Moroccan Locust in Cyprus are on the central Mesaoria plain enclosed between the Troodos mountain range and the northern Kyrenia range. This plain is almost entirely cultivated but there are numerous flat limestone and sandstone outcrops, around and between which no cultivation is possible. These 'islands' of undisturbed soil with short grass cover, appeared to be particularly suitable for the breeding of the locust, which appeared mostly in concentrations’ (Quoted in Jennings, p.309).

It seemed that the short, sparse vegetation of the uncultivated islands and borderlands of the Mesaoria (from Morphou to Famagusta and the Kyrenian Hills to Larnaca) with its low rainfall and thin hard and practically impermeable limestone crust (kafkalia) found on or just beneath the surface was ideal for locust reproduction (Jennings, p.310).

By now the biblical swarms and marching hopper bands (that occurred before the adults could fly) had been eliminated. However, the ideal breeding grounds often bordered arable crops that still suffered grievously from locust depredation.

Various solutions were put forward to reduce the areas of kafkalia including tree planting and the efforts to convert this into good quality pasture (which is inimical to the locust).

Locusts were both endemic in Cyprus (the common locust) but desert locusts and Moroccan locusts could also fly the distance between Cyprus and Syria or Anatolia. (In the case of the former with relative ease and in that of the latter only with the assistance of the strong and prevailing northerlies that blow between the Turkish mainland and Cyprus).

It is unclear if the type of locusts that have caused such problems for Cyprus stayed the same or varied over time. From the mid-nineteenth century it seems the Moroccan locust was the main culprit.

From the historical evidence it appears that the locust problem arrived on the island shortly after the Black Death in 1348 and from then on was a chronic and debilitating presence in Cyprus until the middle of the twentieth century.

If this is the case what was it that changed on the island to allow the locust to escalate so dramatically and with such catastrophic and periodic consequences?

One candidate (other than the desuetude and depopulation brought about by the Black Death itself) for this change was the increasing deforestation of the island (and particularly the Mesaoria) under the combined demands of the copper- and by this time growing sugar industries for charcoal and firing wood.

One theory goes that the removal of this shade-cover from the marginal vulnerable soils of the Mesaoria allowed processes of weathering, erosion and desiccation to promote the formation of the uncultivated, hard, dry kafkalia-based soils that were the ideal breeding ground for the locust (see my note* below).

See also my page on the Carob Tree and the confusion over St John the Baptist's diet in the desert. Generally it is argued that he ate 'locusts' that is, insects (accompanied by honey) but an alternative interpretation that appears to orgininate in the West argues that the 'locusts' he ate were in fact Carob seeds from whence the Carob seed supposedly gets its common name in English - 'locust bean' and the tree its alternative name as 'St.John's-bread'.

Reliefweb reported that swarming locusts made a surprise reappearance in Cyprus in November 2004 (see also BBC News). Annual rainfall in Cyprus is falling (see my Water page) and the problem of the locust on the island may not be over.

Sources:

Orr, Captain CWJ (1918) Cyprus under British Rule.

Jennings, RC (1988) The Locust Problem in Cyprus, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 51:2.

* Note on Kafkalia:

Kafkalia or kafkall is the local Cypriot term for caliche, calcrete or petrocalcic horizon and capstone and is formed through soil formation rather than deposition. Kafkalla crust is hardest at the top and merges downward into a softer material,

Kafkalla formation is primarily caused by ascendant lime precipitation where evaporation brings lime-saturated water to the soil surface.

'Under natural (pre-clearance) conditions on Cyprus, warm climate encourages vegetation growth, and vegetation reduces evaporation from the soil and precludes kafkalla formation'

Source: Schirmer, W., (1998) Havara on Cyprus - a surficial calcareous deposit, p.116 (download here).