II. Ancient History in Cyprus: Neolithic to Roman

Introduction

The history of Ancient Cyprus is amazingly complicated and has been much contested. As will be seen on the Kourion page the identification of 19th century Europe with Classical Greece hugely skewed archeological exploration and interpretation.

By and large, European archeologists in Cyprus were concerned to prove links with Classical Greece and Hellenism more generally. In one instance, such was there disdain for non-Hellenic ancient artefacts that they were given away to local people as water pots.

So there has been a need to try and understand the ancient past of the island more in its own terms. But this too has become problematic in that the (failed) 19th century project to create a Greater Greece - of which calls for enosis (unity with Greece) from Cyprus formed a part - and the twentieth century partition of the island has created played a part in privileging one particular field of historical enquiry over another.

Cyprus at the crossroads of the Ancient Mediterranean World

Yet one of the unique things about Cyprus and its history is that it springs from its size (never big enough to be a regional power) and location (at the crossroads of the Eastern Mediterranean between Asia Minor, the Middle East, North Africa and Europe).

Lying across the sea-routes of the world she had always been the direct concern of any maritime power whose lines of life stretched across the inhospitable and warring East. Genoa, Rome, Venice, Turkey, Egypt, Phoenicia - through every mutation of history she was sea-born and sea-doomed.

Lawrence Durrrell Bitter Lemons of Cyprus, p.156

It is but 43 miles to the Turkish coast of Asia Minor, 76 to the Syrian coast and 264 to Port Said, Egypt. Piraeus, port of Athens, stands 500 miles to the north west. On a clear day Cyprus can be seen from the Turkish and Syro-Palestinian shores.

Says eminent Cypriot archeologist, Vassos Karageorghis, 'It is significant , therefore, that her importance in history is out of all proportion to her size' (1982) p.12.

The physical geography of Cyprus is also, of course, important. An island measuring 138 by 60 miles at its maximum dimensions Cyprus is dominated by its two mountain areas - the great oblong of the Troodos Massif in the West - an ancient area of raised seafloor surrounded by sedimentary rocks of limestone, gypsum, chalk and marls - and the long chain of the Kyerian Hills rising to 1000m in North East made up of hard limestone.

To the north of the Kyrenian hills runs a long and thin plain of very fertile soils fed by perennial springs. To the south are the plains of Morfu - made up of fertile ferric soils and the Mesoria - 'between-the-mountains' - plain of less fertile soils used to grow the majority of the island's grains.

In ancient times it is likely that the island was covered in forest, that became increasingly marshy on the lower lands. The mouths of river - now silted up - that may have run throughout the year provided a number of natural harbours for the relatively small craft of ancient traders.

River valleys running between the highlands and the plains attracted the first settled communities - as at Khirokitia. Internal communications were relatively easy apart from the isolated Pafos district, cut off by the Troodos mountains.

There is little evidence of major climatic changes in ancient Cyprus, although the felling of the forests on the plains for copper smelting transformed these from cool, shady, relatively well-watered areas to dry, harsh and hot plains that became an ideal environment for plagues of locusts (see my Locust page).

Sea breezes still keep temperatures bearable, compared to the Middle East, and the presence of springs and groundwater has favoured the cultivation of a wide range of fruit, vegetables and nuts. Drought and torrential autumnal rains and hail are an ever present problem and the island's location on an active seismic belt (see my Seismic Activity page) has spelt destruction for many ancient towns and buildings.

See Karageorghis 1982 pp. 11-15

The history of Cyprus is largely the history of conquest and subjugation by a range of kingdoms and peoples from East (Assyria, Persia, Phonecia), South (Egypt and Ptolomeic Hellenism), North (the Ottoman Empire) and West (Mycenaens, Classical Greece, Rome, Venice, the Lusignan knights, and Britain).

And yet Cyprus was big enough and remote enough to never simply adopt the ways of its rulers. Its people, although constantly changing were able to adapt, and add to, and mix in the influences with each wave of more or less intensive invasion and subjugation. This seems particularly evident with regard to the artistic and craft developments of ancient Cyprus.

Whilst bearing in mind the above comments here are some traces of history of Ancient Cyprus with photographs.

Simplified Chronological Chart for Ancient Cyprus

|

Cultural Phase |

Approximate date |

Dominant Foreign Power |

|

|

Proto-Neolithic |

10000 - 7000 |

|

|

|

Neolithic |

7000 - 4000 |

|

|

|

Chalcolithic |

4000 - 2300 |

|

Early Bronze |

|

Early Cypriot |

2300–2000 |

|

Bronze Age |

|

Middle Cypriot |

2000 - 1650 |

Minoan |

|

|

Late Cypriot |

1650 - 1050 |

Myceneans |

|

|

Cypro-Geometric |

1050 - 750 |

707-669 Assyrian |

Iron Age |

|

Cypro-Archaic |

750 - 475 |

669-644 Egypt 545-345 Persian 333 Alexander the Great |

|

|

Cypro-Classical |

450–300 |

||

|

Hellenistic |

300–50 |

Ptolomaic Egypt-based Hellenic rule |

|

|

Roman |

50–400 AD |

Rome |

|

|

Late Roman/Early Byzantine |

400AD –700AD |

Constantinople and the Arab Caliphate |

|

Source: Developed from British Museum, Karagheorgis 1982 and Cyprus Rough Guide 2009

The Neolithic and Early Bronze Age 10000-1700BC

Khirokitia is representative of a wider range of settlements discovered in Cyprus. It is now believed they were settled by people arriving from the Syro-Palestinian coast in around 6600 BC. This phase of settlement appears to have been relatively short-lived and had ended by 5500 BC. For a thousand years there was no further settlement on the island.

The following Sotira culture (4600-400 BC) had no connections with its predecessor. By this time an extensive ceramics industry had been born and continued on Cyprus to the present. The demise of the Sotira culture seems to have been rapid and possibly precipitated by earthquakes.

The Philia culture (4000-2500 BC) which follows the Sotira, bears similarities with it but also profound changes. This was the beginning of the Chalcolithic age (literally, copper-stone age) and although slow to start the use of metal became pronounced in around 2500 BC. These changes are most evident in the north of the island and metalwork and pottery show strong affinities with southern Anatolian techniques. It is possible that these techniques were brought by refugees fleeing some kind of catastrophe. By 1950 BC the Middle Bronze Age was well under way and for the first time there is evidence of indigenous copper mining and tin/copper bronze became fashionable.

By this time the whole island was occupied but for the mountain fastnesses although strong regional variations were present. By the 1700s BC Cyprus came out of its isolation and trade increased with imports and exports to and from Egypt and the Middle East although communities were still predominantly agrarian and inward looking (See Tatton-Brown, T. (1987) Ancient Cyprus pp. 12-13.

Aceramic Neolithic Stoneware, Khirokitia

The Late Bronze Age 1700 - 1200

The late Bronze Age was a period of great richness and settlement shifted towards the coast as trading contacts became more important. Close trading contacts are evidenced from the 1500 BC with Egypt, the Near East and the Greek mainland. A hundred years later the island was a major exporter of copper to the eastern Mediterranean.

All was not plain sailing. The destruction of the principal cities in Mycenaean Greece and the emergence of the raiding 'Sea Peoples in the early 12th century BC had an impact on the island and Cyprus suffered violent destructions. Prosperity returned later in the 12th century BC and most of the population was by now living in five large towns.

The increased intensity of trading contacts in the eastern Mediterranean had it impacts on cultural expression which as this time owed debts to Syria, Palestine and the Aegean.

The Mycenaeans 1200-1050 BC

Myceanaean impacts from the Greek mainland and Crete were most noteable in the areas of writing, bronze work and sealstones and this may have been occadsioned by the gradual arrival of settlers from the Bronze Age Greek world.

But in other areas the 'culture remained untouched by Greek influence.' Burial customs were unchanged and a strong Cypriot tradition in ceramics continued. The weight system reflected Near Eastern and Egyptian customs and eastern influences were apparent in religious practices.

It is suspected that Mycenaean settlement intensified in the 11th century BC and the Crypto-Minoan script that developed in the 1500s BC was replaced by Cypro-Syllabic and the Greek language. Pottery reflected Aegean motifs and New Mycenaean Greek burial practices began to emerge (so to speak) (see Tatton-Brown Ancient Cyprus 1987 pp.14-15).

The Dark Ages and Phoenician Influence 1050-850 BC

The ‘Dark Ages’ (1050-850 BC) followed the waning of the Mycenaean era. However, trading contacts with east and west were maintained and a strong Phoenician influence begins to assert itself evidenced in the local production of Phoenician metalwork and ceramic motifs.

The Archaic Period 750-475 BC

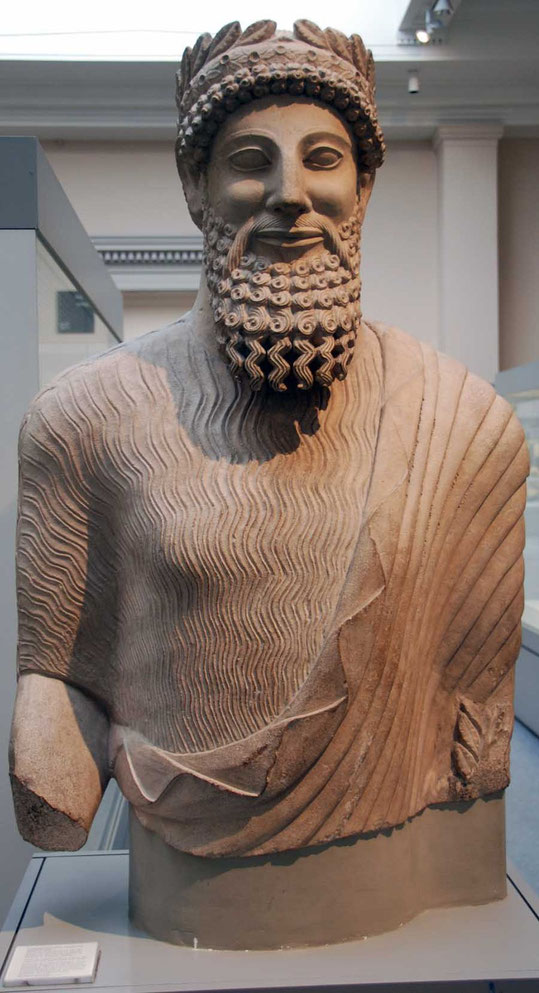

During the Archaic period (750-475 BC) Greek influences were much weaker. In 707 BC the Cypriot kings submitted to King Sargon (722-705 BC) of Assyria. Although Assyrian rule was not punitive and local kings maintained their wealth and relative independence the influence of Assyrian art and sculpture were dominant. Following the collapse of the Assyrian empire in 669 BC Egyptian rule of a more severe kind than that of Assyria was established for 25 years. However, during these years there was lively commerce with Aegean and Ionian Greece and Karageorghis argues that there were Cypro-Greek and Cypro-Egyptian influences on the development of sculpture with a sometimes difficult-to-assimilate fluctuation between Orient and Occident (See Karageorghis, V 1982 Cyprus: From the Stone Age to the Romans, Thames and Hudson, London p.139).

Internally the island was organised into seven and then ten autonomous city-kingdoms. There is some evidence to suggest these were ruled by Greek incomers although Kition remained under Phoenician leadership. This influence grew in the fifth century BC as Phoenicians ruled at Lapithos and briefly at Salamis, the most powerful Greek kingdom, and at Idalion and Tamassos in the mid-fifith and fourth centuries respectively.

The city kingdoms had wide trading contacts and by the sixth century BC they were striking their own coinage.

The Classical Period: Persian domination and Greek ties (475-325)

In 545 BC the kings of Cyprus submitted voluntarily to Cyrus, King of Persia. This developed into ‘hard slavery’ for the Cypriots that was to last 200 hundred years after all of the city-kingdoms, save Amathus, had joined with the Greek cities in Ionia (part of modern Turkey) in the Ionian Revolt (499 BC). (Karageorghis,1982 p.152)

Throughout the Classical Period Cyprus was poised between mainland Greece and Persia. Mainland Greek commanders tried to make the island a base but the Persians reasserted themselves. From 411-371 BC the island's politics were dominated by the philo-hellenic King Evagoras of Salamis who controlled a large part of the island by 391 BC with the support of Athens and Egypt.

The treaty of Antalkidas (387 BC) saw Athens recognise Persia's sovereignty over Cyprus and Evagoras's influence was pushed back, first into his kingdom of Salamis in 380 BC and then with his murder in 374 BC.

The Cypriot kings continued to make common cause against Persia after a period of internal feuding but Persian rule kept coming back. It was finally overturned at the Battle of Issos where the Greeks under the leadership of Alexander the Great, King of Macedon, beat the Persians. At this point 200 years of Persian rule was over and the island's city-kingdoms submitted voluntarily to Alexander (Tatton-Brown Ancient Cyprus pp.16).

Ptolomaic Rule

Cyprus became a battle-ground after the death of Alexander in 323 BC as his generals sought to inherit the kingdom. In 294 BC, Alexander's general who had successfully claimed Egypt, annexed Cyprus and for the next 250 years the island was ruled from Ptolomaic dynasties from Egypt.

The island was organised as a military command with the leading roles - the Governor (Strategos) and his minions - directly appointed by Egypt and in the hands of non-Cypriots. Limited local democratic forums were introduced and some minor Phoenician dynasts were allowed. Overall, the island was oriented to the Macedonian Greek traditions of the Ptolomies and although the copper, timber and corn resources of the island were exploited by Egypt it was a relatively peaceful time for Cyprus.

The excavation of the Marion kouros 520-10BC gives an insight into the complexity of the melting pot of different cultural influences in Cyprus at the time. The contents of the tomb included other items of Greek origin, Phoenician items (most probably made by local Phoenician residents), an Egyptian alabaster alabastron, and Cypriot products’ including a silver coin – stater- from Idalion – on the obverse this has a figure of a sphinx.’

The Romans 58 BC - 330 AD

Initially Cyprus was handed back to the Ptolemies as a gift to Julius Caesar's mistress, Cleopatra VII. This was short-lived when Augustus, first Roman emperor, took Alexandria and Cleopatra committed suicide in 30 BC.

Cyprus was first incorporated into the Roman empire as part of the province of Syria but later became a Senatorial Province for three hundred. Amongst the Senator's given the province of Cyprus was Cicero. The province was organised as four districts (Paphos, Amathus, Salamis and Lapithos) and Paphos was the capital city.