Historical Sites II: Khirokitia

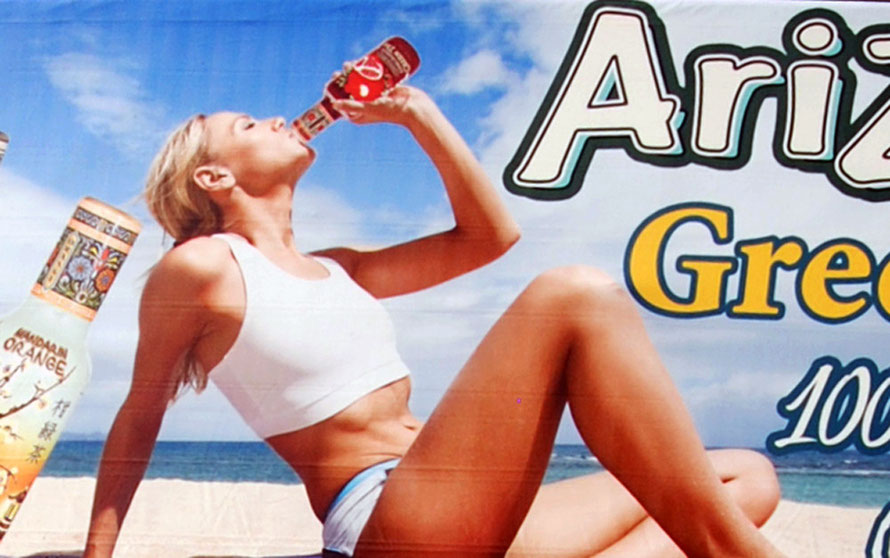

The A1 motorway from Nicosia to Limassol passes across the southern spur of the Troodos massif and through delightful carob and wheat country to the south, with views of the distant hill-top Stavrovouni monastery. It also passes a massive billboard of a girl in a bikini drinking 'Arizona Green Tea'.

This is a beverage sweetened with high fructose corn syrup, ("light" teas are half-corn syrup and half-sucralose, while diet drinks are solely sweetened with Splenda-brand sucralose). They are made by the Arizona Beverage Company which is headquartered in Woodbury, New York.

You wonder what the Aceramic Neolithic dwellers at Khirokitia, just off the motorway, would have made of it all 8,000 years ago.

I had driven right by Khirokitia a number of times. I'm really glad I stopped there one absolutely baking day in mid-June: it was 80oF at 9 am and 104 oF later.) I stopped again in January 2013 when it was a lot cooler and had a walk into the valley behind the settlement (see bottom of this page).

Situated on the Maroni river 6 km from the sea the settlement subsisted on raising domesticated sheep and goats and raising grains and lentils, hunting and gathering wild fruits such as pistachio nuts, figs, olives and prunes.

The settlement had a population of 300-600 and life expectancy was 33-35 years for adults.

Khirokitia is representative of a wider range of settlements discovered in Cyprus. It is now believed they were settled by people arriving from the Syro-Palestinian coast in around 6600 BC. This phase of settlement appears to have been relatively short-lived and had ended by 5500 BC. For a thousand years there was no further settlement on the island (V. Tatton-Brown Ancient Cyprus 1987 pp. 12-13).

The settlement of Khirokitia is situated on a steep-sided knoll. The round houses - tholoi - some of which were for storage, are tightly knit behind a high external wall.

The were built of rubble on the outside and mud brick on the inside. At Kalavassos–Tenta one of the internal walls was painted with a human figure in red ochre. Some had attics and a type of veranda. The largest house had three adjoining tholoi which acted as storage or workshop rooms (Karageorghis, 1982 pp. 18-19).

They houses step down the steep south facing slope of the knoll. There was a sophisticated entrance system to the settlement to make unwanted ingress difficult. However, the excavation of the site revealed no evidence of weapons or hostilities.

The whole site had long disappeared under the later terracing of the least rocky sections of the knoll. The day I visited in mid-June the sun was fierce and it was stinkingly hot. Zephyrs

of cooling breeze blew in from the sea to the south. Fitfully. The Sling-Tailed Agama lizards were out in force on the baking rocks.

Khirokitia is a brilliantly preserved example of the so-called Aceramic Neolithic (i.e. they had no pottery). The technique of baking clay had not yet been discovered but a wide range of tools and vessels were discovered at the site. These were made of chert, flint, diabase, limestone and bone. Some of the stone vessels in the Cyprus Museum are beautifully made and must have required a high degree of technical ability - not to say patience - to avoid splitting the stone.

The thin-walled stone bowls, made out of grey andesite are elegant and decorated with grooved or relief patterns, carefully rendered spouts and polished surfaces.

Aceramic Neolithic Stoneware, Khirokitia

The settlement at Khirokitia was inhabited between 6600-5500BC. An earlier settlement has been discovered at Akrotiri-Aetokremnos on the steep cliffs at the end of the Akrotiri peninsula. A dense concentration of bones including those of the Pygmy Hippopotamus (phanourios minutus) and the endemic Dwarf Elephant (elephas cypriote) were found in the cave. This settlement may have been for occasional hunters rather than a long-term settled community.

At another settlement, Parekklisia-Shillourokampos, inhabited between the 9th and 8th millenia BC obsidian blades attested to trading links with the Anatolian mainland. Evidence of the domestication of cattle was found here but appears to have died out before the Khirokitia era.

The Maroni valley behind the settlement would have provided a supply of fresh water - I could hear frogs croaking down there in the middle of June. A small of area of flat land could have been used to cultivate eincorn and emmer wheat. The hills that would probably have been wooded would have been full of game and wild fruits and nuts.

Plants at Khirokitia in mid-June 2012

Lizards at Khirokitia

The Sotira culture - 4600-400BC - that followed the Aceramic Neolithic 'had no connections with its predecessor. By this time an extensive ceramics industry had been born and continued on Cyprus

to the present. The demise of the Sotira culture seems to have been rapid and possibly precipitated by earthquakes (V. Tatton-Brown Ancient Cyprus 1987 pp. 12-13).

The Sotira culture was followed by the Stone/Bronze Age (Chalcolithic) and brought profound changes to the the island (see Ancient History).

I have embedded a video by Girl Archeologist of the Sotira settlement below. The cicadas are loud and the crackle from the mike sounds like thunder and made me think something huge was prowling on our roof.

Khirokitia valley, January 2013

I passed by Khirokitia in very different weather in January 2013. The day before had been the coldest of the year with plenty of snow on the High Troodos. The following day was blessed with warm sunshine.

I had meandered my way down from small roads off the N2 through the rolling hills of carob and wheat and passed by some of the one-time Turkish Cypriot villages in this area. Seeing the abandoned houses and mosques had filled me with a rancorous melancholy on such a lovely day.

I ended up driving up a tiny, practically abandoned road in terrible condition that was separated from the N2 by a thin crash barrier - the traffic on the adjacent carriageway hurtling towards me. I wasn't sure quite where I was but felt I was heading in the right direction, if in an unconventional and slightly alarming fashion. A situation not helped when I dusty battered pick-up came barreling down the track towards me.

The very willing Suzuki Splash braked well and after topping a steep climb chuntered me down into a placid valley. I came to a junction and realised where I was: at the mouth of the little valley that runs up behind Khirokitia.

Last summer the valley had been baked dry when I looked down into it from the Khirokitia settlement. Now it looked very tempting.

I climbed out of the car and a chap with a big, nicotine-stained moustache, shades, baseball cap and backpack came walking along. We exchanged a 'Kalemera' and got to talking in English about the pleasantness of the day, the harshness of the preceding weather, and the big freeze grinding down on Russia. It turned out the guy, who I assumed was a local Greek Cypriot, was from Brooklyn, New York. We made our farewells and he headed off into the nearby cafe for his coffee. It would have been interesting to hear his story of, I assumed, emigration and return.

It really was a remarkable day: the sky a scintillating ultramarine blue, the sun beneficent, the air pure, warm, redolent of the not-so-far-away sea.

I climbed the steep rocky track skirting the valley floor and little lemon orchard tucked in down by the stream. A butterfly floated by. Birds sang. Distant voices called across the fields. A scent of spices hung in the limpid, welcoming air.

I passed a bright orange sign declaring that this was a Wildlife Conservation Area and that Hunting was prohibited - in Greek, Turkish and English. Littered on the stony ground was a a concatenation of spent shotgun cartridges of every colour imaginable (for shot gun shells that is). Did they stand here of a weekend and shoot into the Conservation Area, I wondered. Or maybe someone put up clay pigeons for the local afficianados.

Early spring flowers, Khirokitia valley

I followed the track down to the valley floor, took a look at an old abandoned dwelling, noted the big dog tracks in the wet mud of the roadbed, wondered at the amount of debris swept down the little stream by winter rains, searched wistfully for a loosened Aceramic Neolithic antiquity in the wash and gravel and along the freshly eroded banks of deep, fecund soil. To no avail.

But it was blissful to be alive there and then and to know that this valley and its tight valley-floor fields had been cultivated for over 8,000 years.

Video of Sotira settlement with 'Girl Archeologist'