Notes on the Historical Context and Significance of the Kouros in Archaic Greek Art

Hello. I've noticed that this is one of the most viewed pages on my website. I'd be really interested to here from you and how you arrived here. Leave me a note via my Contact page if you have the time. Many thanks. Fergus (May 2016). Enjoy the page. You might also like to see my Kouros Drawings.

Contexts

The heyday of the kouros was between 580BC and 480 BC.

The kouros was an important marker and maintainer of an order threatened by a strong collective anxiety about chaos and disorder. Pollitt (Art and Experience in Classical Greece, 1972) argues that the Archaic period was not, as if often imagined, ‘a happy springtime of Western civilization.’ In this context, he argues that the figure of the kouros transcends ‘ the imperfect world of everyday experiences and [is] unaffected by its travails’ (p.15)

The kouroi were an expression of a strong homogenising force of conformity – the ‘over-riding characteristic [of the small city-states of the Archaic Period] was the pressure exerted on the individual citizen to merge his interests in those of the group’ (p.10)

The expanding Persian Empire threatened and eventually conquered and crushed the upstart city-states of the Eastern Mediterranean in 494 BC. Only the remarkable Greek victory over the Persian navy in 480 BC restored a semblance of confidence that prefigured the emergence of the Classical period.

The Archaic is often seen as ending with the creation of the Kritian Boy in 480 BC. Kenneth Clark hails it as ‘the first beautiful nude in art’ (see Spivey, 1996 Understanding Greek Sculpture: Ancient Meanings – Modern Readings, Thames and Hudson.)

Spivey labels the Kritian Boy the ‘cover boy’ of the Greek Classical Art Revolution as defined by modernism. He adds that this is part of a greater project of Western writing and culture that sought to construct a connection between the ‘perfection’ of Classical ancient Greece and individual liberty from the 18th century onwards in Western Europe (p.21.

Artistic Contexts

Spivey (above) argues that the Greek Revolution reacted against three millennia of autocratic Egyptian rule that had ordered the production of an ‘entirely predictable art.’ (p.26)

‘One ingredient of this revolution was the battle of three-dimensional art against two-dimensional Oriental styles.’ Ibid 29.

Spivey also mentions the commonplace existence of pederasty as in the courtship of young men by their elders. He notes the existence of male beauty cults - euandria – that celebrated 'fine manliness' and understood ‘a beautiful mortal [to be] pleasing in the eyes of gods’ (p.36).

The Kritian Boy is an athlete with a ‘taut but not over-muscled body’, a ‘pert bottom’ and a ‘clean jaw’. He has a rather moody set of features and ‘seems to think for himself’. As such to some extent he is ‘his own man’ (p.36).

In contrast to Bruenau (2006) (see 'Greek Art' in Sculpture - from Antiquity to the Present Day, Taschen 2006) who tries to plot out a linear movement towards realism based on the increasing skills of Greek craftsmen Spivey see the achievement of the Classical nude as something other than a triumph of skill and perception.

The Classical male was almost oppressively exemplary – standing for moral integrity, military commitment, civic virtue, athletic prowess, sexual desirability, personal salvation and immortality. (Spivey, p.39)

That is quite a lot to live up to. It is also understandable why the emerging imperial powers of the 18th and 19th centuries were so keen to articulate and project themselves within this vision. On this, I walked through the rather quiet and snowbound New Town in Edinburgh recently. It was striking to go from one Romano-Greek statue and building to another where worthies, dressed in nothing but togas in the big freeze, tower above the ordinary citizenry. As if there superior morality and enterprise could protect them from the atrocious weather.

As Spivey puts it,

Classical beauty was charged with goodness – it had a moral and religious quality of god-laden beauty – kalokagathia (p.39).

Kouri were grave markers and votive offerings.

Content

Pollitt suggests that the kouroi look past you in the museum with impassive faces (p.15) bearing a characteristic Archaic smile that,

is not so much an emotion as a symbol, for they are beyond emotion in the ordinary sense of the word. (p.9)

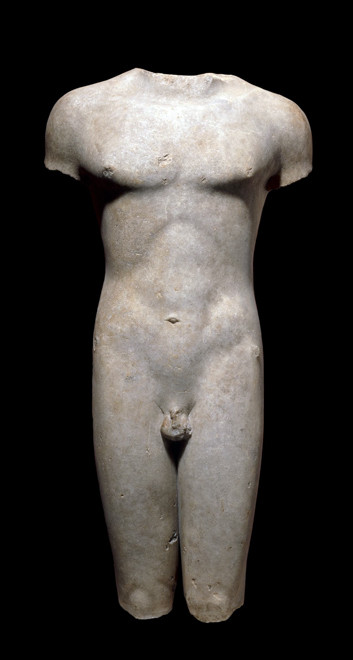

The kouros was a youth or ‘stripling’ with long hair, broad shoulders, athletic waist and a spring in his step carrying some of the ‘poetic attributes of the god Apollo’ and as such they were intended to honour Apollo and other gods. (Spivey, 2000, Greek Art, Phaidon).

Kouri have a flexible range of significance as grave markers and votive offerings. Spivey estimates that by the end of the 6th century BC there were 20,000 in Greece and that ancient Greek culture was agonistic (agonizethai) in that it was competition-driven for the achievement of specific prizes – as encapsulated in the games at Olympia where,

Winning was of paramount importance even to the point of death ...and where losers were booed with derision (p.135).

Nudity and Sexuality

The kouri are hugely influenced by, and maybe even step out of, Egyptian body motifs. One great difference is that the kouri are not rulers – at least in an explicit sense, nor are they derived from known individuals. As such they do not carry the symbols of office so often carried by Egyptian sculptures – staff and rolled script.

But perhaps the biggest change is the lack of clothes and the shift to total nudity in men/youths. Whereas the kourai (young women) are clothed.

Spivey links sport, military service and readiness to fight and the commitment to fight as a condition of citizenship and participation in a decision-making democracy (2000 p.143)

He also draws attention to the symposium - so much in evidence on Greek pottery. A coming together of primarily men (women are often either serving girls or sexual partners) to talk, make music, and drink.

The gymnasium was also an important site of bodily display - gymnos meaning naked.

Davidson is interesting on pleasure in Ancient Greece. (Courtesans and Fishes: the consuming passions of classical Athens , Davidson, J., Fontana, 1998.)

His main thesis is that the Greeks were not afraid of pleasure but that they were afraid of overindulgence and dissipation through pleasure. So they were passionate for fish, they liked drinking but not boozing, they were OK with paid heterosexual sex and homosexual sex with women and young men and gifts for sex with the courtesans (hetaeras) although love with them could be disastrous.

In this they were candid and able to discuss and pursue pleasure openly:

the Greeks imposed few rules from outside, but felt a civic responsibility to manage all appetites, to train themselves to deal with without trying to conquer them completely’ (Davidson p.313).

Elsewhere he says, ‘All men felt the draw of pleasure very powerfully and most at one time or another succumbed’ (p.144).

The Greeks ‘considered a fierce struggle against desire a normal state of affairs. They saw themselves as exposed to all kinds of powerful forces. The world’s delights were lying in wait to ambush them around the next corner. And yet people naturally wanted to indulge as much as possible in things that were enjoyable' (p.142).

Anatomy

The kouros are often strangely un-anatomical. Spivey mentions the existence of an iliac crest on the back as well as front of the torso.

The shift from Archaic to Classical representations of men marked a watershed for art, according to Boardman (Boardman, J. ‘Introduction” in Boardman, (ed.) (1993) The Oxford History of Classical Art, OUP).

The realization that the artist could effectively improve on nature through realistic representation rather than relying on conceptual formulas through which to express the natural world occurred in Greece for the first time in the history of man (p.5).

However, that realistic representation was not an empirical realism but more a,

shrewd combination of observation and that long dominant interest in design and proportion (p.5).

So what does one conclude? That the beauty of the kouros is moral, god-pleasing, erotic, pure, elegant, innocent, available, civilized, calm, balanced.

That they are:

an offering;

a status symbol of individuals and competing city-states;

a marker (of graves);

a protector (of the dead);

and an appeaser/pleaser (of the gods).

They are monumental, schematic, formulaic, and mostly (in as much as they have survived to our times) made of marble.

Their features are learned and added to – there is a development over time. The pose comes from Egypt and the hair from Assyria. But as Richter and others show there is both a regional specificity of style and a progression towards greater awareness of human anatomy (Richter, G.M.A. Kouroi, Archaic Greek Youths, A study of the development of the Kouros type in Greek sculpture, 1960 - the Wikipedia Kouros entry reprises her progression).

They are free-standing and they are not supported by the stone column used by the Egyptians for stability. They are more in-the-round although still primarily frontal in pose and depiction. The simple forms become more complex.

The Kouri are very different from men as portrayed in Classical sculpture. They are not their 'own men' and are naked to the consuming eye. They do not attempt to dominate the viewer with their sense of busy-ness, prowess, self-possession and reflexivity.

They move steadily toward the viewer, slim waisted, well endowed (a small penis was later fashionable as larger genitals, and their arousal, were associated with bestiality, satyrs and ungoverned desire).

The kouri are pleasure boats, idealised young men, smiling, willing and yet remote. They walk out of their aloneness, their separation from the viewer. But seem to stay in it.

Maybe the kouri are portrayed more like women were to be portrayed in western art – passive, restrained, demur, devoid of a sense of tractable, bounded assertive individuality.

Robin Osborne (Archaic and Classical Greek Art OUP 1998) suggests that,

The man who looks on a kouros finds himself being looked upon by a figure that is male and impassive: here is a male who stands firm, unbending and constant. Such a figure makes a dutiful servant to the gods or to the city, but also an image of the unageing constancy of the gods themselves (p.81).

Osborne argues that the transition from archaic to classical greek sculpture can be read as a transition from an art that concerns the solidarity of humanity in its struggle with known and fixed boundaries,

the gaps between man and beast or man and gods

to an art that explores human identify in the sense of ‘the place of the individual human within a human community’ and the way in which individuals negotiate their positions within a more fluid society and set of power relationships.

Materials

The kouroi are made of marble – a treasured medium that was hard to work, labour-intensive, hard to transport and very durable. The first (known?) marble statue is Artemis at Delos (650BC). Before this wooden images – xoana – were predominant (Spivey, 2000 pp.119-20).

This relates to a blindingly obvious but easily forgotten point that Bruneau makes: namely that we only know antique art through the art that has survived.

There were four forms of sculptural material in Ancient Greece – wood, stone, clay, bronze and chryselephantine – a combination of gold and ivory. Bruneau argues that the order of prestige of these materials was from chryselephantine, through bronze to wood and marble. He suggests that marble was not prized and that this was evidenced in its use for works of secondary importance – such as architectural work, votive and funerary reliefs and large-scale pieces (op. cit. p14). Thus it is an historical accident ‘that the material most commonly found today [marble] was relatively mediocre in Classical antiquity’ p.15.

On this it is also worth mentioning that most of the extant kouros remains are not complete sculptures but fragments of the originals.

This is hugely important in the rediscovery of Ancient Greece in the 18th and 19th centuries – the fragment in the museum becomes the whole and/or attempts were made to reconstruct the whole by joining fragments from different pieces of sculpture or by refashioning/recarving the missing pieces (often the extremities). This may have had a profound impact on the contemporary perception of the body by shifting the gaze onto specific areas of the body – in particular the torso and bust?

Methods

Spivey (2000) allows considerable weight to Egyptian monumentality, tools and techniques – for examples the formulaic and idealised proportions of the male body. However, he argues that,

the competitive endowment of Panhellenic sanctuaries by individual city states was chiefly inspired the move towards monumentality (p.122).

Bluemel (Greek Sculptors at Work, Phaidon 1955) surmises that marble sculptural figures were worked down layer-by-layer in the round. He says,

Small wonder, then, that so much vigour emanates from a Greek sculpture, since at every layer it was rethought by its creator, who thus charged it with extra strength (p.13).

He suggests that Greek marble sculpture is predominantly opaque, granular and yellowish-grey. The sculptures themselves were created by ‘stunning’ the marble with a heavy ‘point’ (stone chisel forged or ground into a point). This method of working marble fractured the fine crystalline structure of the stone and gave the work a ‘velvety depth’ – a technique used by Egyptian carvers who were working in granite which required more force (p.19).

But it is amazing how little is said about the process of making Kouroi. This in part is because the people who write about art don’t generally make art and have little detailed knowledge of the processes of making it. And it is also due to the scarcity of knowledge about Archaic Greek carving methods and tools.

The quality of steel available to carvers would have been crucial and that quality would determines the edge a particular steel could hold and the durability and fineness of the tool itself. It is interesting that the kouros literature with the possible exception of Bluemel does not consider the quality of bronze, iron and steel available to Archaic and Classical Greek carvers.

If, as Bluemel implies, tools were based on a heavy point – which is, as the name suggests, a pointed piece of metal not unlike a large pencil – it is not surprising that carvers were limited to figures where the natural brittleness of marble was counteracted by strong, pillar-like structures with no free standing arms or legs, let alone fingers.

The incredible virtuosity achieved by Giambologna in, for example, The Rape of a Sabine 1581-2, was technically way beyond the reach of Greek carvers. This was presumably to do with the qualities of both the marble, the tools that Giambologna had access to and the techniques developed by Renaissance sculptors. This seems to be born out by the much greater compositional freedom achieved by later Greek sculptors when they began to model in clay prior to casting in bronze – see for example the Riace bronzes.