Hilary Spurling, The Unknown Matisse and Matisse The Master

I am reading Hilary Spurling’s 2 volume biography of Henri Matisse. It is a real revelation. I had somewhere along the way picked up the notion that his art had come to him easily, magically formed and flowing as easily as cool water from the base of a limestone cliff.

The story meticulously unfolded by Spurling from his huge correspondence and her tireless research shows an absolutely driven and obsessive man battling with himself, his family, his and their health and frequent derision throughout his career. Nothing can be allowed to stand in the way of his art and his ferocious desire to succeed against formidable odds. The martyrdom of his wife, Amelie, and children, Marguerite, Jean and Paul, in the cause of his art is at times shocking and yet he was capable of great kindness to them and his succession of young models.

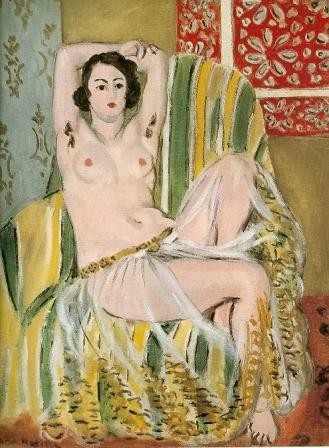

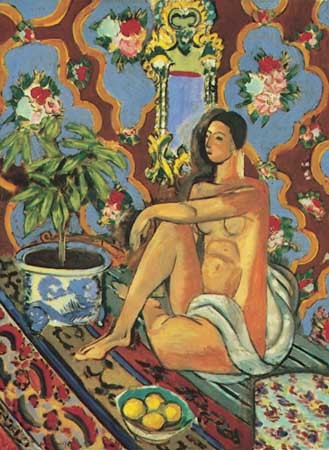

The book is also fascinating on Matisse’s relationship with his models – nearly exclusively young women in their late teens and early twenties. Spurling is adamant that there is no evidence of sexual involvement, predatory or otherwise, with the possible exception of Olga Meerson, a student of Matisse’s who was madly in love with him. But the relationship between artist and model, often long-lived as in the seven years Matisse drew and painted Henriette Darricarrere, was intense, mutual and solitary – says Spurling

In the seven years they worked together, Matisse multiplied variations on the same theme with ferocious audacity in paintings, drawings and prints. (Vol II:248)

Often his models became part of the family and there seems to have been little tension between Madame Matisse and their presence, even when, as often happened Henri was working in Nice and she was taking care of business in Paris. For more on this see Matisse and his models.

Nor had I realized how he was reviled and mocked both by the art world of the Academy and Picasso and his cubist chums who at one time launched a graffiti campaign against Matisse on the walls of Montmartre (Vol II:64). When his paintings were first shown in Chicago in 1913 the students of the Art Institute of Chicago burnt copies of his works and staged a public trial for treason against ‘Henry Hairmattress’ (Vol II:136).

But the boy from the damp grey North East of France, son of seed merchants, was eventually to triumph and force new developments out of his failing health, often under the critical tutelage of his children who kept him from backsliding or falling into pastiche. At one point, tried beyond endurance Matisse, a hardened unbeliever, admits to praying what might be called the artist’s prayer:

Give me strength to resist, patience to endure, and constancy to persevere. (Vol II:352)

In this Spurling recounts the following:

Sex, in fact, was one of the things Matisse grumbled about having to do without in Nice. So far as modeling went, he applied the same rules to human beings as to a fish dinner. “I’ve never sampled anything edible that had served me as a model . . . ,” he explained, describing a plate of oysters brought for him to paint from a nearby café by a waiter, who later fetched them back to serve to his customers at midday. Matisse said it never occurred to him to tuck into his oysters for lunch: “It was others who ate them. Posing had made them different for me from their equivalents on a restaurant table.”

Perhaps what is most interesting, is the joint endeavor of artist and model working together, of finding a way of looking and being looked at intently that transcends the rage of lust, erotic possession and subjugation to find a kind of charged and attentive calm – Matisse’s great painterly goal – that allowed Matisse to portray the dignity, beauty and autonomy of the model.

At the same time the social and sexual relations of early twentieth century Europe were hardly conducive to equality between men and women and I’m sure there are art historical analyses that castigate Matisse and his use of young women as passive adornment – like a plate of oysters - for his, and his gender’s, Orientalist fantasies.

Critical influences on Matisse’s art were the Islamic art of Spain and Grenada in particular and Russian iconography.

Hilary Spurling, The Unknown Matisse and Matisse The Master, Two Volumes, 2005 Hamish Hamilton

The reviews of the Hilary Spurling Matisse biography at the time of publication were generally positive and the second volume won the Whitbread Prize. Jackie Wullschlager in the Financial Times is unreserved in her praise. John Elderfield, chief curator of painting and sculpture at MOMA, New York is more circumspect in The Guardian. He wants more art history and exploration of Matisse's creative process and less exposure to the master's, as he more or less puts it, interminable whinging.

Spurling is certainly fulsome in her account of Matisse's anxieties and troubles but he had a lot to be worried about and his times - he lived through three Franco-German wars - were anxious and tragic. That he did not succumb to collaboration - of which others have accussed him - or go into exile but doggedly kept on making his art as an antidote to barbarism (see for example the awful description of the Gestapo torture of his daughter, Marguerite) says a lot for his tenacity, which also kept him from embracing the widespread adulation of Stalin amongst France's post-war artistic and intellectual elite. Indeed, his slogan might have been, to paraphrase the old SWP mantra: 'Neither Russia nor Rome, but international luxe, calme, et volupte'.

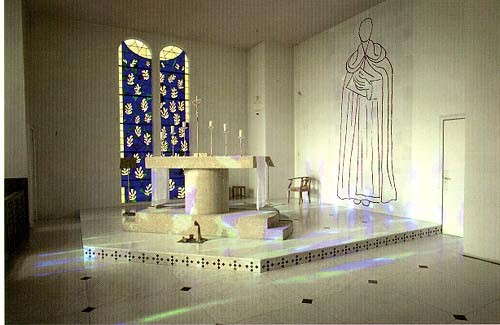

The book climaxes with Matisse's decoration of the purpose built chapel at Vence from his mobile bed-ambulance and his death shortly thereafter. His helpmate, love, carer, and business manager, Lydia Delectorskaya - who had devoted herself entirely to Matisse and his work and failing health for 15 years - picked up her packed suitcase and - her work done - left Matisse's household hours after his death.

One thing else that I learned from the book is that there is a Matisse Museum at Le Cateau Cambresis in the North of France, near the Belgian border, where he grew up. This was founded with a gift of 150 paintings from the artist. It's two hours from Calais.

Towards the end of his life Matisse complained gloomily to his daughter, Marguerite, that artists were victims of random circumstance:

'Artists are like plants whose growth in the thicket of the jungle depends on the air they breathe, or the mud or stones among which they grow by chance and without choice.' (449)

The denizens of an outpost of the Bloomsbury set made great and merciless play of the nearby 'gloomy' and 'boring' Matisse. One of the strengths of Spurling's account is her reluctance to label Matisse - unlike Elderfield who is happy to call him narcissistic - and let the narrative speak for itself. And she is good at locating the narrative within its broader political, social, artistic and familial context.

Matisse's fateful groan about the artist's helplessness and dependence on chance is belied by his own life. He was an obsessively active protagonist in his own fate and in this he was backed by the absolute commitment of his wife, Amelie.

Matisse may have had some bad luck: most of his work was locked away in Stalinist Russia, or in Nazi Germany or behind the locked doors of an American collector but he had some luck too: he had access to the educational, economic and emotional resources to get himself to Paris with enough drive and self-belief to sustain and develop his art practice in the incredibly dynamic milieu of early 20th century Montmartre.

This was the 'air' that he breathed in the fecund jungle of early Modernity as it squared up (cf Cubism ha ha) to the stultifying academic art systems of the late 19th century.

His 'mud' was the solid agricultural and industrial tradition of Northern France, of the small-time merchant success of his parents, and a resilience, belief and enterprise ('aspiration', we'd call it now) that seemed to spring from this.

Perhaps less explicitly commented on in Spurling's work were the gender relations of Matisse's time that enabled him to enlist a string of devoted women into his artistic project and organisation. It was they who put the food on the table, organised the household and artistic business, and protected and buoyed him up in the face of the derision of both the art academy and many of his contemporaries.