Brancussi's Studio and Art in a Domestic Setting

I finally had a look at a book I have had out of the library for too long. It is called Constantin Brancusi: Shifting the Bases of Art and is by Anna C. Chave and was published by Yale University Press in 1993.

The book seems to be a largely social and psychoanalytical feminist analysis of the importance and context of Brancusi - 'the most important sculptor of the Twentieth century' (p.4) and his sculptural output. It is very well illustrated which was one of its attractions for me.

I found I did not have the energy or time to engage with Anna Chave's more high falutin theses about Brancusi's sculpture and changing male and female relations around sexual reproduction, the rise of a new Narcissism and the collapse of male authority and Platonic absolutes. But I liked what she had to say about Brancusi's studio:

Brancusi's art never looked better ... than it did enshrined in the model environment he arranged for it in his combined studio and home. This private, yet practically public space (the studio was, in effect, the artist's only European gallery), with its continualy reorganized contents, was in a sense Brancusi's most fabulous opus, though an ultimately ephemeral one.'(p.21)

Brancusi hardly left his viewer's to walk amongst his sculpture, but guided them through it in an apparently dramatic and unchanging manner for four decades. Indeed, the informed visitor could anticipate the artist's moves and revelations in what became something of a 'Paris stunt' that nevertheless made an impression lasting enough to lead to the recreation of his studio in front of the Pompidou Centre.

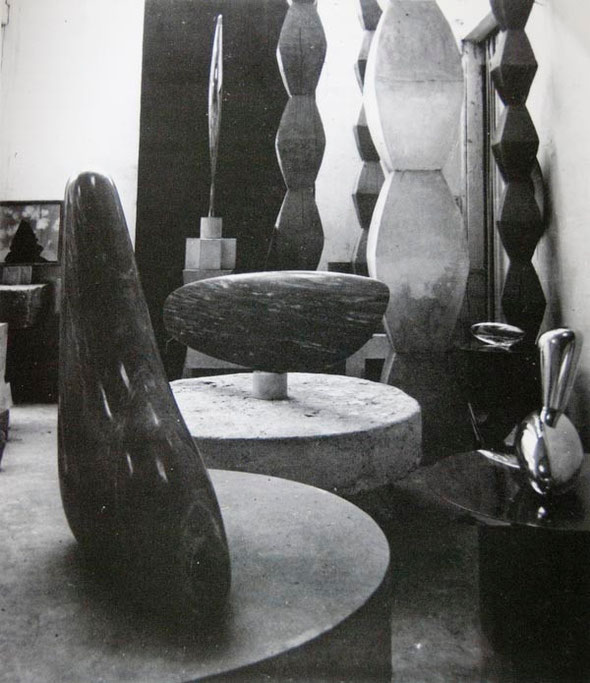

Brancusi's photos of his studio arrangements also remind me of some of Joseph Beuy's work, particularly The Tramstop, where made objects are grouped in a way that seems both random and tightly choreographed so that the open and forbidding space of white box is tamed and coralled into something that is playful, irregular and also deeply serious. There's a lovely photo in the Chave book (7.6 Column of the Kiss) where Brancusi has made a collection of pieces in the corner alcove of his studio that gives a kind of protective and conversational aspect to the work (see above).

And Brancusi's black and white photographs of his studio installations are stunning with their juxtapositions of his different pieces of work with the natural light from the studio skylights creating brilliant tonal ranges. In these photos I am staggered by the absolute purity of line that Brancusi achieved, and beautiful and intimate effect the clusters of his work achieve in the muted light of the studio.

Brancusi was an assiduous cultivator of his own persona as mystic and hermit labouring slowly in monastic isolation - he was actually a highly garrulous bon viveur and acutely aware of contemporary art developments - and the impression his studio gives is that of a beautifully arranged temple, cave or devotional chapel.

But that aside there is a magic in putting pieces of sculpture together in confined, apparently cluttered, spaces that for some work seems to work much better than their display in the traditional white box of contemporary galleries. Barbara Hepworth's studio and garden in St Ives in West Cornwall is a lovely example of this effect where the sculptures and works-in-progress in their walled garden seem to multiply and humanise, soften and juxtapose the impacts of the often quite austere sculptures themselves. This seems to make the whole much richer than the sum of its individual parts. Chave says of Brancusi, "He liked to present his sculptures amid other work ...and amid raw materials and tools. In that way his vision could be seen to outreach any single object, even to encompass 'another world.' " (p.274)

Chave concludes that Brancusi's attempts to make his studio a world separate and complete from the contemporary world could not succeed. His strategy also seems to have a lot to do with the creation of the myths and the absolutes of the controlling male artist who fools himself that contingency and and happenstance only effect the hesitant and the weak.

A friend recently asked me why I had apparently 'eschewed the market-scene' and not put my work in galleries or up for sale. I made some stumbling reply that my reticence was not informed by any grand anti-commodification principle, although there is something to be said for it at least in the abstract, but that it was more to do with my own insecurity about the worth of my work and its ability to stand as a 'body of work' with a degree of coherence, and thematic, procedural or material unity.

But I now also wonder if my reluctance to have a show has also something to do with the very everydayness (quotidianity?) and the intimate (as in familiar) quality of my works in our home and my studio.

If that is the case then I have possibly betrayed myself in the way I present my work on this website, having been cajoled into compliance with a dominant discourse that presents sculpture in isolation and 'in the round' rather than 'in context'.