The Norwegian Atlantic Wall

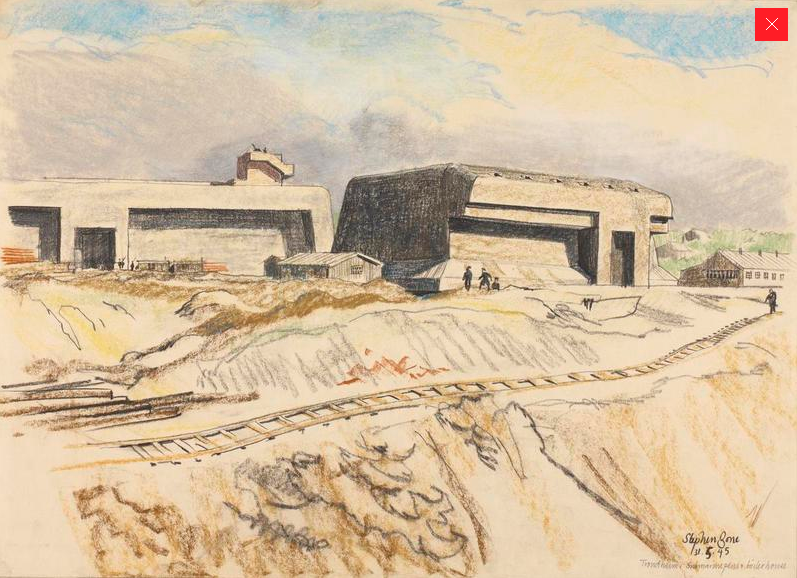

The Atlantic Wall was a massive series of coastal and port defences constructed by the Nazi regime from Spain to the very far north of Norway. Jasinski says, 'It was probably the greatest single construction project undertaken in the world during the twentieth century' (Jasinski, 2013 p.149).

The Norwegian Atlantic Wall was supposed to create a Norwegian Fortress (Festung Norwegen) that was part of the Atlantic Wall designed to repel any invasion of mainland Europe from Britain. In Norway at the end of

the war it consisted off 221 coastal batteries divided into 29 units and 10 regiments divided between German army and navy artillery units. There were 126

coastal batteries in far northern Norway alone (see Marianne Lucie Skuncke).

These were manned by three German army corps. Under the Nazi leader of the German forces in Norway, Reichskommissar Josef Terboven, a plan was conceived

to turn Norway into a fortress - a last redoubt - Festung Norway in the event of the fall of Germany.

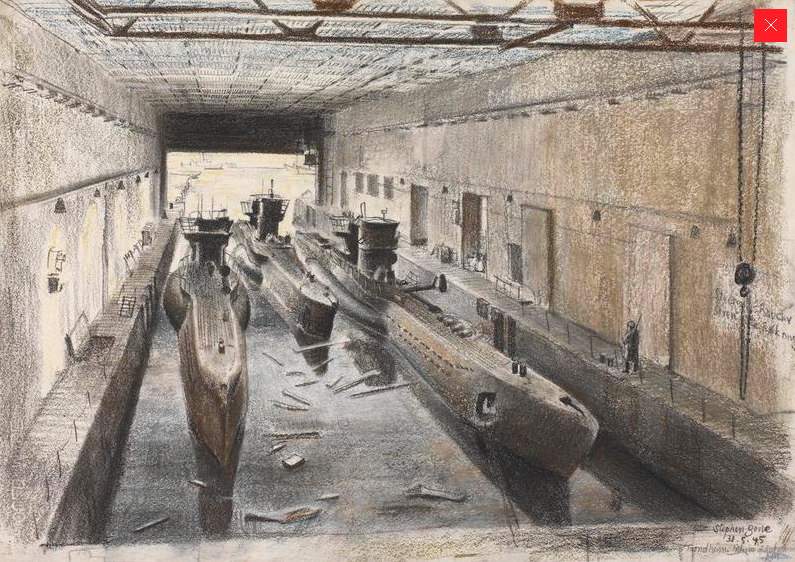

The Norwegian Wall was also motivated by what some have called Hitler's 'obsession' with Norway and the 'Northern Flank' as an area of 'destiny' for Germany and its Reich. This in part sprang from the desire to create havens and bases for German Navy ships and U-boats from which to harass Allied shipping in the Atlantic.

Hitler also wanted to secure the iron ore from Sweden that was shipped via Narvik. Although Germany had access to huge amounts of iron ore the ore from the Swedish mines was particularly good for making special steels for armaments and keeping it out of Allied hands became a priority. Hence the fierce fighting over Narvik in 1941 (see here The Adolf Guns).

There was also a desire to attack Russia through Arctic Norway and Finland - in operations called Silver Fox, Platinum Fox and Reindeer. This planned to capture Murmansk and push on to Leningrad (St Petersburg). In order to do this huge effort had to be put into creating communications link with the far north of Norway, particularly as sea links were severely disrupted by British and Russian naval attacks. The operations were unsuccessful (with the death of 10,300 German soldiers) and the Murmansk Front was in stalemate until the Russian Petsamo-Kirkenes offensive in 1944.

There was presumably also something in the attraction to Norway that was informed by German theories of racial superiority. The Norwegians were not Slavs and fitted in with Aryan racial stereotypes. The 'Lebensborn' programme administered by the SS was an initiative to encourage encourage Norwegian women to bear German children. The SS 'provided special mother-and-baby homes where the chosen were treated as pampered recruits to the ranks of the master race' (BBC Crossing Continents, 2001).

This led to a massive investment of men and material in Norway. Of all the occupied countries Norway had the greatest number of Nazi soldiers and PoWs compared to the domestic population. These were used to undertake huge projects - the Atlantic Wall but also the highly ambitious road and rail links to the far north (the Norlandsbanen and Riksvei 50) (Jasinski and Stenvik, Landscape of Evil, 2010, p. 205). (see Blodveien - the Blood Road - for an account of part of the construction of the Riksvei 50 with PoW labour).

Most of these positions had to be constructed on Norway's mountainous and rocky coastline from scratch and required huge amounts of steel and concrete. 65,000 troops were required to man the positions (for the above see Jervas).

It is argued that the Atlantic Wall in Norway was hugely costly to the Nazi regime and tied up 300,000-400,000 German military personnel. The Allies made sure to try and maintain a credible threat of invasion to Norway through elaborate rouses in 1943 (Operation Cockade) and 1944 (Operation Fortitude).

In barely two years, the Wall consumed millions of tonnes of reinforced concrete, depriving armaments factories of vital iron and steel. As Speer recollected during his years in Spandau prison, it had been an exercise in futility: “All this expenditure of effort was sheer waste” (Ianthe Ruthven in Le Monde).

At the height of work in 1944, nearly 300,000 men were coerced into building 60,000 structures ... Many thousands died in terrible conditions, including 500 Soviet prisoners in the Norwegian Arctic not given adequate clothing (Ianthe Ruthven in Le Monde).

Next page: The Lyngen Line