Operation Nordlicht/Northern Light

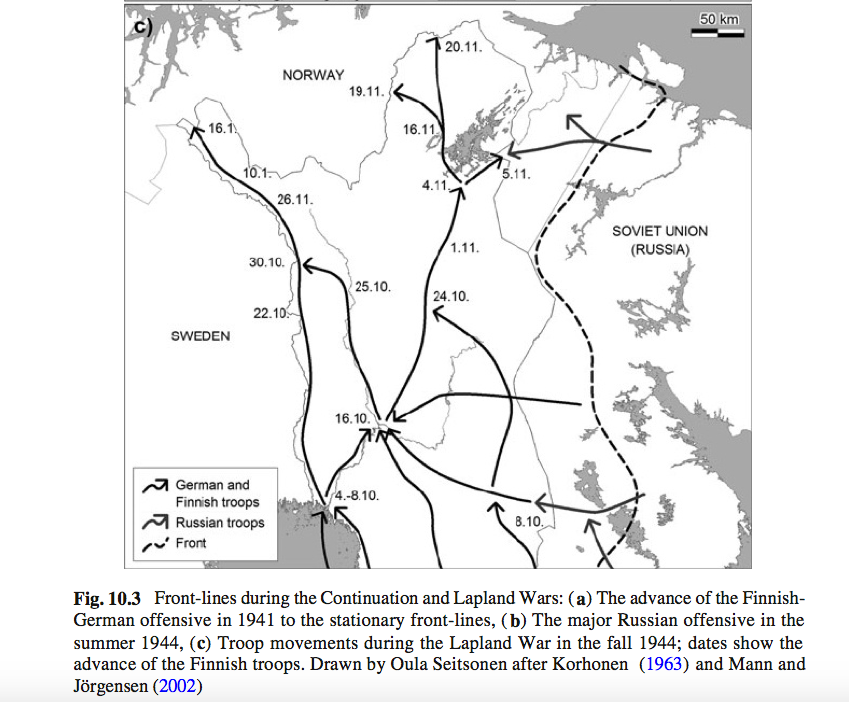

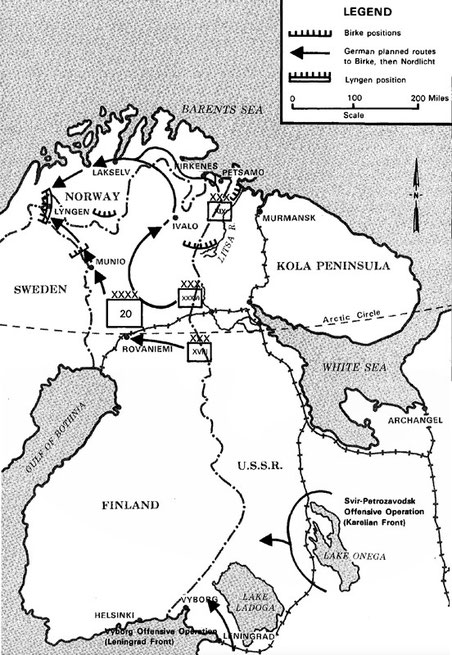

In 1944 Finland signed a peace accord with Soviet Russia. In the autumn of 1944 Hitler (October 3rd) issued an order for the German 20th Mountain Army (Gebirgs-Armee-Oberkommando 20) to evacuate Finland and retreat to Norway.

And on 18 October 1944 Soviet troops crossed into Norway after fighting the gruelling Petsamo-Kirkenes Operation (see the account of this by James Gebhardt, (1990) The Petsamo-Kirkenes Operation, Combat Studies Unit, Ft Leavenworth. See also this detailed account http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/wwii/articles/SovietOffensiveInArctic2.aspx).

We can only imagine the condition under which PoWs were moved to Norway from Finland as the 20th Mountain Army carried out its measured and brutally destructive withdrawal in the Autumn of 1944. By this time the Red Army was making massive gains on the Eastern Front. But Soviet troops did not attempt to push south through Norway and were redirected to the Eastern Front.

In Hunt's Fire and Ice his interviewees make much of the combat craziness of the withdrawing front line troops of the 20th Mountain Army and the 6th

Mountain Division. For example, one interviewee - Roald Berg - says, 'the soldiers from the Murmansk Front were not human. They had seen so many bad things they didn't have any feelings

left' (Chapter 11).

The Nazi regime's withdrawal was code-named Operation Nordlicht ("Northern Light") and the objective, having sent many troops and material by sea from Northern Norway, was to withdraw to the 'Lyngen Line' 1,000 km away and 100km south east of Tromsø to create a bulwark against any possible Soviet advance through Norway. The retreat ended on January 20th 1945.

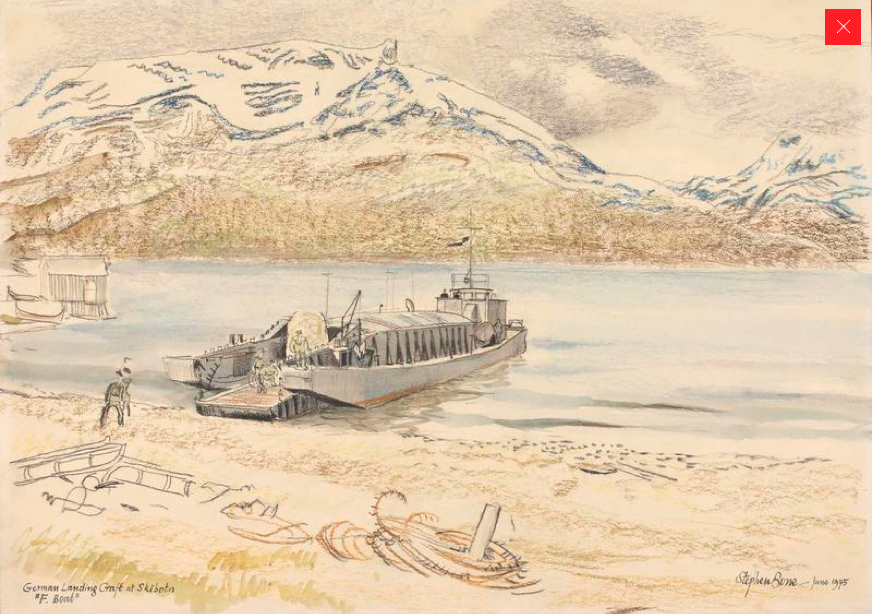

At this time the Third Reich still considered Norway strategically important, particularly for its U-boat bases (see picture below) as the ones in France had been recently lost through the D-day landings. The nickel mines at Petsamo could also be abandoned because Germany had good stocks of nickel (see see Zeimke, J., (2014) From Stalingrad to Berlin: The Illustrated Edition, Pen and Sword Books and online, pp. 502-3).

The German retreat was notorious for the scorched earth policy that it implemented in Finland and Finnmark and northern Troms counties in Norway. The destruction was massive and unrelenting. In Finland,

the Germans destroyed not only their former bases and camps, but also burned down every Finnish village within their reach, in total some 16,000 buildings. Over 1,000 road bridges, some 100 railroad bridges and 40 ferries were blown up; 170 km of railroad, 9,500 km of road and almost 3,000 culverts were destroyed; and most electricity poles cut down. Tens of thousands of head of cattle and reindeers were killed, and over 130,000 land-mines and other explosives planted in the landscape. In the years after the end of the war, these mines would kill about 2,000 people (Kallioniemi,1990:55–61, p.177).

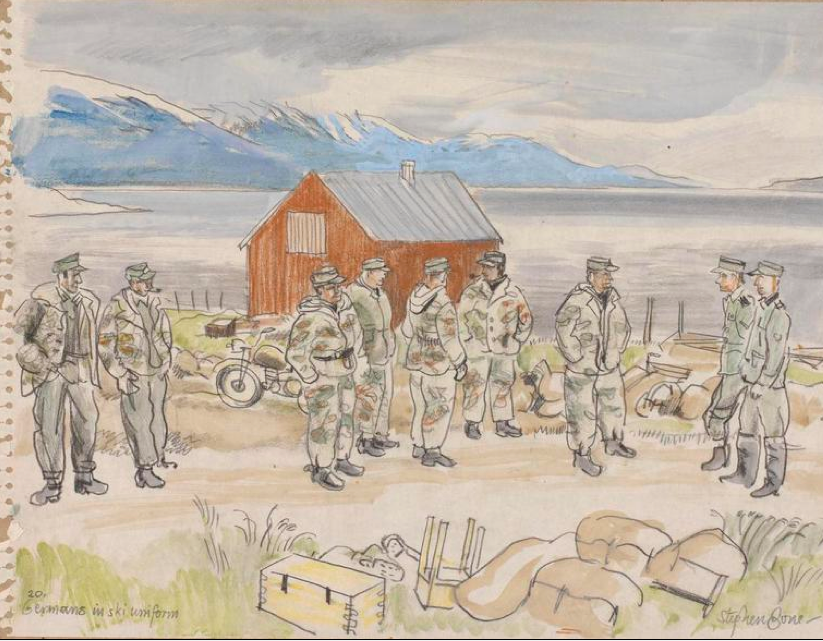

Upon their coming to Lapland, the Germans were quite out of place in this new environment, and even the most well-trained German Mountain Jaegers (many of whom were, in fact, Austrian) were unprepared for the harsh conditions encountered on the Lapland front (e.g. Kallioniemi1990:15) p.183

(From Seitsonen, O. and Herva, V-P., Forgotten in the Wilderness: WWII GermanPoW Camps in Finnish Lapland in Myers, A., and Moshenka, G. (eds.) Archaeologies of Internment, 1991.)

It looks like the withdrawal was accompanied or preceded by the withdrawal of the only SS division in the Arctic - the 6th SS Mountain Division Nord which in September 1944 'marched on foot 1,600 km through Finland and Norway' to Denmark.

The order for withdrawal included the forced evacuation of the entire population of the Norwegian regions of Finnmark - roughly the area of Denmark - and northern Troms. Under

heading Six: Evacuation and Destruction, the order stated,

"All installations which might be of use to the enemy are to be destroyed thoroughly, particularly roads and railroad lines, port installations, airports and other installations of the Luftwaffe, industrial plants, Wehrmacht billets and camps. All snow barriers on the through roads are to be burned in time.

"Rations and other Wehrmacht supplies are to be destroyed unless they can be transported.

"The entire population of Norway capable of bearing arms is to be taken along as far as marches permit and to be turned over to the Reich Commissar Norway for compulsory labor employment.

"Finnish hostages are to be taken along as the situation requires (see Nuremberg Trial transcripts here).

A further order from the German high command of October 28th clearly stated , 'Compassion for the civilian population is uncalled for' (see Nuremberg Trial transcripts here p.2553).

A further order from Lothar Rendulic, commander of the 20th Mountain Army, includes

f. Men capable of working and marching and in the western districts women capable of marching also, are to be coupled to the marching units furthest in front and to be taken along.

g, Inasfar as the population still has small ships available they are to be used for the deportation of the evacuees.

(see Nuremberg Trial transcripts here p.2556).

This order finishes,

7. I request all offices concerned to carry out this evacuation in the sense of a relief action for the Norwegian population. Though it will be necessary here and there to be severe all of us must attempt to save the Norwegians from Bolshevism and to keep them alive." (see Nuremberg Trial transcripts here p.2557).

Rendulic was tried at Nuremberg for war crimes associated with Operation Nordlicht and acquitted. He was convicted of other crimes committed elsewhere (see Aftermath).

No mention is made in this detailed order about PoWs until a resume of the evacuation that notes, 'a smaller residue of workers of the Wehrmacht is to be moved off later with the unit' (see Nuremberg Trial transcripts here p.2565. Pages 2562-3 give details of the place and boats used to forcibly evacuate the population).

Parts of Finnmark had already been devastated by the war - the Norwegian town of Kirkenes had been bombed 328 times (the only place to be bombed more in IIWW was Malta). And the forced evacuation of the entire population of Finnmark was part of the German's withdrawal plans. Incidentally, this doubled the size of Tromsø, from 10,000 to 20,000 which remained relatively intact during the war (see 'Norway's Liberation' by Tor Dagre).

The Germans destroyed 11,000 houses, 4,700 cow sheds, 106 schools, 27 churches, 21 hospitals 22,000 communications lines and,

'roads were blown up, boats destroyed, animals killed, and 1,000 children separated from their parents. ... When war was over, more than 70,000 people were left homeless in Finnmark. The government imposed a temporary ban on residents returning to Finnmark because of the danger of landmines. The ban lasted until the summer of 1945 when evacuees were told that they could finally return home (Wikipedia: Finnmark).

The main road running south to north was destroyed into impassibility beyond Lyngen and as one commentator dryly puts it,

'the measures resorted to in the absence of active pursuit exceeded those which may be considered necessary in military operations'.

43,000 to 45,000 people were forced out of Finnmark and northern Troms although 20-25,000 managed to avoid the exodus. The commander of the 20th Mountain Army, General Rendulic, was a committed Nazi and many of his officers complained of the treatment of the civilian population and local commanders at great risk turned a blind eye and allowed some families to stay.

Most were forced to take to the Barents Sea in small boats to move south in order to keep Reichestrasse 50 clear for the withdrawing troops and material.

8,500 nomadic Sami people were exempted from the evacuation order issued by Hitler on October 28th 1944 (see Lunde, H.O., Finland's War of Choice p.368).

Ferdinand Jodl, commander of the 19th Mountain Corp, subsumed under the 20th Mountain Army, argued against the evacuation. In the first place because,

my unit which is absolutely exhausted by the various attacks and offensives has something else to do than to deal with evacuations and destruction, we are glad if we can bring our 5,000 wounded into safety to the West and can get supplies of the most necessary things, materials, et cetera. We have no columns in order to transport population (see Nuremberg Trial transcripts here p.2579).

He also believed that the Russians would not pursue the withdrawing Germans as most of the Russian troops assembled for the Petsamo-Kirkenes Operation had since been transferred to the Eastern Front. Jodl argued that the forced evacuation would create,

miss givings [sic] and ill will amongst the Norwegian population and embitterment and this embitterment can be of no practical use to us (see Nuremberg Trial transcripts here p.2579).

Operation Nordlicht was a huge and risky undertaking.

As an expedition by a 200,000-man army with all its equipment and supplies across the Arctic in winter it had no parallel in military history. The season was already far advanced. Reichsstrasse 50, the German-built coastal road in northern Norway, was normally considered impassable between Kirkenes and Lakselv from early October to the first of June because of snow; ... The road the XVIII Mountain Corps would use was about half completed between Skibotten and Muonio [in Finland] unimproved between Muonio and Rovaniemi; its low-carrying capacity was at least in part compensated for by its being the most southerly and direct route to the Lyngen Fjord

(see see Zeimke, J., (2014) From Stalingrad to Berlin: The Illustrated Edition, Pen and Sword Books and online, pp. 502-3).

The 1000km march from Kirkenes to Lyngen took about six weeks - in one case from the 12th October to 20th November (see witness statement Nuremberg Trial transcripts here p.2608). It is hard to imagine such a journey through the dark, freezing Arctic winter with very few places in which to stop and find shelter overnight.

General Rendulic described the withdrawal thus at the Nuremberg trial where he was one of those accused of war crimes during the forced evacuation of Finnmark and north Troms,

The army was spread over an area of 500 kilometers. That is, it was spread over a wider area than, for instance, the Allied forces in France and these forces [in France] were more than a million men strong. The problem was to relieve this army out of an encirclement from three sides and that, in battle with a superior enemy. Then this army would have to be concentrated on two highways and, finally, it would have to march along only one highway. All that would have to be done on foot and in the Arctic winter. Nuremberg Trial transcripts here p.534.

The German withdrawal from Finland and Finnmark apparently constituted an 'outstanding display of skill and endurance.' But it was also lucky. The weather was good and winter that year was late in arriving and the resources of the Russians and Allies were 'stretched to the limits on ... [other] fronts'.

The withdrawal was accompanied by a flanking movement by the 7th Army Division which occupied the finger of Finnish territory north east of the Lyngen Line to protect the main north-south route ('Reichsstrasse 50'). The 7th Division stayed at Sturmbock until January 12th 1945 'when it began a leisurely march back to the Lyngen position, which in the meantime had been manned by the 6th Mountain Division' (for this more detailed information see Zeimke, J., (2014) From Stalingrad to Berlin: The Illustrated Edition, Pen and Sword Books, pp. 502-3).

Over 50,000 troops and 6,030 vehicles were ferried over Lyngen Fjord in November 1944 (see Lunde, H.O., Finland's War of Choice p.368).

Seitsonen and Herva note that during the retreat The German 20th Mountain Army,

took some 9,000–11,000 PoWs with them and at least 1,000 unfit prisoners were left behind. There is some evidence to suggest that the Germans had moved over 10,000 PoWs to Norway and Germany already before the outbreak of hostilities between Finland and Germany in the fall 1944 (p.177).

Very little mention in the military accounts is made of the PoWs. Hunt in

Fire and Ice: The Nazis Scorched Earth Campaign in Northern Norway

On some days these undernourished men had to walk ... 30km with wooden shoes with rags or paper bags for socks.

The prisoners slept outside (this was in October and November 1944) making fires where they could. (Ch2)

In her report Laila Lanes says that many elderly people remembered seeing 'endless rows of prisoners of war from the autumn of 1944 come walking by roads in North Troms.' One boy remembered his mother telling him about them,

She talked about when the first Russian prisoners came in the autumn, hundreds of prisoners arrived at the farm, they broke down the forest and lit bonfires to be able to survive the night. ...

They also heard gunfire, and many froze to death, the day after the dead were picked up in trucks.

From the report by Laila Lanes of 28.10.2014 of the NRK.

For the Nuremberg trial that covered the Finnmark 'scorched earth' events see the page Aftermath at the end of this page.

Next page: The Atlantic Wall in Norway