Norway: a very short introduction

This page is a work in progress and gets less short by the day.

It appears and looks like paradise on earth. The fourth richest country in the world by GDP per head. A country with a greater land area than the UK and a population of 5.3 million people. An abundance of natural resources from the fish in the sea to the oil and gas under it, forests and green energy and a habitat of fjords, islands and mountains.

A welfare state of legendary generosity and a level of personal income that has risen rapidly in comparison with other European countries. And to top it all, a sovereign wealth fund that equates, at $870bn, to an investment per head of population of $173,000.

Norway, officially the 'Kingdom of Norway', is a sovereign and unitary monarchy. Its territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula plus Jan Mayen and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard. Until 1814, the Kingdom included the Faroe Islands (since 1035), Greenland (1261), and Iceland (1262).

Norway has a total area of 385,252 square kilometres (148,747 sq mi) and a population of 5.109m people (2014).

It is bordered by Sweden (a frontier of 1,619 km/1,006 miles long), Finland and Russia to the north-east, and via the Skagerrak Strait to the south, with Denmark on the other side. Norway has an extensive coastline, facing the North Atlantic Ocean and the Barents Sea (see Wikipedia Norway).

Norway has a per capita GDP of $67,445, the fourth highest in the world and a low Gini index - 22.3 - representing modest levels of inequality. This compares with Scotland (population 5.327m) which has a GDP per head of $45,904, the 19th highest in the world and a Gini index of 32.8 (Wikipedia: Scotland and United Kingdom). Norway's GDP per head is 46.9 per cent higher than Scotland's and is 184% of the EU 28 2013 average.

Norway, along with Lichenstein and Iceland, is a member of the European Economic Area - an anomaly for European countries which wanted the benefits (and burdens) of the European Union whilst retaining certain key sovereign rights - which in the case of Iceland and Norway seems to largely concern the protection of their rich fishing grounds in a huge zone of economic exclusivity.

It is a deeply Eurosceptic country (recent opinion polls show three-quarters - 72% - of the population opposed EU membership although in the 1972 and 1994 referenda on membership those against were 53.5% and 52.2%) and yet in return for access to the European single market Norway has to implement 'nearly all' EU regulations whilst having little say in their formulation. This has recently become an issue with Norway's resistance to implementing EU offshore safety rules that were tightened up after the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Norwegian environmental groups are sceptical about their government's reasons for refusing to implement the regulation.

Jonas Helseth, director at Bellona Europa, a Norwegian environmental group said, “Norway should have learnt by now it can’t cherry-pick the EEA agreement and would be better off actively contributing to sound legislation."

Norway is richly endowed with natural resources including oil and gas, hydropower, fish, forests, and minerals. In 2011, 28% of state revenues and 50% of exports were generated from the gas and oil industry.

About half of Norway’s total business investment in recent years goes to building and maintaining rigs on Norway’s continental shelf and to maintaining the pipelines that pump the oil from the North Sea to the mainland and the rest of Europe (FT Alphaville).

Norway’s oil production has been consistently falling for more than a decade and is now half its level in 2000.

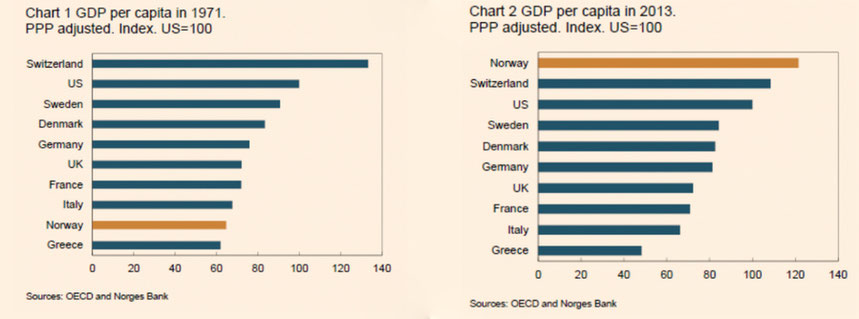

'In 1971 — when the North Sea oil was just beginning to flow — the average Norwegian was about as poor as the average Greek' and Swedes were much better off. By 2013 this situation had been dramatically reversed with Norwegians 50% richer than their eastern neighbours (see charts in FT Alphaville ).

Oil wealth has also pushed up house prices and massively increased household indebtedness - 30 year-olds face a debt of three times their disposable income. House prices have doubled in ten years. A friend in Tromsø renting a subsidised 40 sq m flat was paying £900 per month rent and Tromsø house prices are said to be similar to those in London. People have undertaken high debt in the expectation that GDP and house prices will continue to rise. Were they to fall by 30% one in four households would hold negative equity.

Norway has the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world and in August 2014, the Government Pension Fund controlled assets valued at US $870 billion. That's equal to 174% of Norway's current GDP. Norway owns more than 1% all publicly quoted stocks in the world and 2.5% of those in Europe. The holding per head of population of the sovereign wealth fund is US $173,000.

The Norwegian welfare state benefits hugely from the sovereign wealth fund as the government is allowed to spend up to 4 per cent of the $850bn oil fund each year in its budget (FT). Four per cent of $850bn is $34bn. In 2015 the Norwegian government run by a centre-right coalition planned for the first time to spend 3% of the sovereign wealth fund to bolster government spending.

Norway has a mixed economy. The state owns about a third of the value of the companies listed on the Oslo stock exchange. This is supplemented by the holdings of a sister institution to the sovereign wealth fund. Around 285 000 people, or 11% of employees are employed in companies with partial or complete state ownership (OECD Country Survey 2016).

The state, then, has considerable holdings in Norway's large companies - the largest are oil producer, Statoil (67% state holding), Norwegian telecoms firm, Telenor (54% state holding), aluminium producer, Norsk Hydro, and fertisliser producer, Yara (36% state holding), airline operator, SAS, property business Entra, airport train Flytoget; construction services provider, Mesta, manufacturing conglomerate, Kongsberg Gruppen and banking, DNB Bank.

So, for example, the salmon farming outfit, Cermaq, which produces 170,000 tonnes of salmon a year (10% of global production) in its operations in Norway, Canada and Chile. The state had a 59 per cent holding in the company, plus a 6.4% stake through a state investment company. In 2014 Mitsubishi Corp offered NKr8.88bn ($1.4bn) to acquire the company from the centre-right Norwegian government, which had promised to reduce state ownership of Norwegian businesses.

Apparently, Norway's best known business man is John Fredriksen, (aka 'the Viking King') the billionaire ($11.9bn in 2013) shipping magnate and owner of seafood producer, Marine Harvest. In March 2016 Fredricksen sold a third of his controlling share of Marine Harvest for $510m.

His holding company, Geveran Trading Co., now owns 17.7 per cent of Marine Harvest's share capital which is worth about NKr9.313bn ($1.07bn). See this article in Forbes on some of Fredriksen's other holdings, his rags-to-riches story, his $200m Chelsea home and his citizenship of 'tax haven', Cyprus.

The John Fredriksen Wikipedia entry makes reference to the Gard case in which Fredriksen paid an out of court settlement to a Norwegian marine insurer, Gard Assuranceforeningen, of $800m. A brief account of the case is given here. And here for the problems confronting drilling rig owners, amongst them Fredriksen's SeaDrill, in the face of the collapse of the oil price in early 2016.

Oil dependency has its downsides. Eleven per cent of employment is highly sensitive to global oil demand with knock on effects in other sectors and Norwegian wages have outstripped those of its trading partners in recent years - although this has been ameliorated by depreciation of the Norwegian krone. Still, in October 2014 the average health care worker was being paid 60% more than their US counterpart. (It was 80% before the recent currency fall). And in 2013 hotel and restaurant staff were getting more than two and half times the US equivalent wage.

By international comparison personal taxes, unit labour costs and, to a lesser degree, corporation tax are high.

I get the impression of a rather corporate economy and society with high levels of state ownership and industrial dynamism in key areas: oil and gas and related industries, shipping, fishing and aquaculture and the decline of more traditional industries.

While the oil and gas continue to flow and the oil price is maintained at a level to continue further offshore development this model can probably go forward. But oil revenues are down as production falls and the oil price is putting a big dent in both tax receipts and the profits of oil producers and related industries - oil rigs, shipping etc.

The OECD is of the opinion that there are considerable efficiency gains to be made in the public sector, much of which is administered by Norway's 428 municipalities (130 of which have less than 2,500 residents) whilst there is a general need to cut bureaucracy and red tap (see OECD Country Survey, 2016).

Similarly, whilst per pupil education spending is very high outcomes are only middling and completion rates in vocational courses are 'weak'. There are also problems in higher education with some low student satisfaction scores and weakness in terms of international rankings given spending on the sector. On the other hand, participation rates are high although timely completion is problematic and post-education literacy is worrying in 10% of graduates.

With regard to welfare 10 per cent of the working population now receive disability benefits compared to 6.5% in the UK. And among 60-64 year-olds, one third of women and nearly one quarter of men are on disability benefit.

Norwegian agriculture is one of the most heavily subsidised sectors n the world with each agricultural holding receiving payments of on average €62,000 per annum, equal to 60% of gross farm income. Further support is given through import tariffs on foodstuffs, which push up average food prices. The OECD (2016) argues that it is time to reduce farm subsidies in Norway and link them more strongly to cultural and environmental goals.

Aquaculture and fishing subsidies have been much reduced which has led, again according to the OECD, to expansion and more economically competitive fleets.

Since 2013 Norway has been governed by a centre-right minority government of the Conservative and populist Progress Party (which won 16% of the national vote). .

In this brief interview (FT video) with the Financial Times, Siv Jensen, Finance Minister and leader of the Progress Party, talks about the passing of peak oil investment, structural reforms - particularly a lower tax burden - declining productivity growth and wiser spending. One of the policies pushed by the Progress Party was a ban on street begging (FT video on this and article).

In April 2014 the centre-right government and populist Progress Party Finance Minister, Siv Jensen, abolished the SWF's Ethics Committee leaving all investment decisions up to the Central Bank. "Ms Jensen’s own sister, Nina, head of the WWF in Norway, accused the government on Twitter of 'gigantic broken promises' with regard to a failure to radically increase oil fund investments in green infrastructure."

See this useful FT article on the basis and threats to the consensual Nordic industrial relations model, particularly over youth unemployment at over 20% in Sweden.

Norway had 3% growth in 2013 and 3.7% unemployment. Nearly three-quarters of females aged 15-64 are in work, the highest proportion in Europe after Iceland.

Norwegians work the third-fewest hours in the developed world ... have the highest rates of sick leave ... more than one in five children above the age of 16 drops out of school ... [and] school results are below average internationally despite high spending. Productivity growth as in other parts of Europe is an issue -

Norway, Finland and Denmark have all had annual productivity growth of about 1 per cent in the past decade compared with 2-3 per cent in the 1980s (FT article on Nordic model problems)

As we flew through the low cloud towards Tromsø I really had no idea what to expect. I knew almost nothing about Norway. I had the standard Brit Norwegian toolkit of knowledge: ouch, it's expensive; they've got a lot of oil; some in the Scottish National Party think Scotland can aspire to be Norwegian (ha ha); and don't they produce a lot of farmed salmon (1.2m tonnes, 2016 estimate and significant holdings in Chile, the second world producer of farmed salmon) and have very progressive equality laws. And Ole Gunnar Solskjær. Oh, and that mass killer, Breivik, was that his name?

I thought Norway was a stable, prosperous, and well-ordered society. I knew that the so-called 'Scandinavian model' was under some threat. But I also knew that countries like Norway still meant something, something progressive, and that they punched above their weight internationally, and were on the right side and tried to do good.

I'd read a few books, Knut Hamsun - his first book was published in a bookshop in Tromso (and later, I now learn, became a supporter if not member of Norwegian fascism and a supporter of Hitler - see this book. He was later - much later - reintergrated into Norwegian society and there is now a Knut Hamsun Centre).

I'd watched the film about Laika and all that sadness (My Life as a Dog) but that turned out to be Swedish. I'd even read the first of the Knausgård trilogy on the urging of a mate. The Knausgård was intense but I don't know that it felt particularly 'Norwegian' (but I was reading it in translation), apart from the snow.

I'd also read a novel about living out in the woods in the snow and the Second World War (Out Stealing Horses by Per Petterson). There was a strange silence in the book. Maybe also in the Knausgård. A silence where people found it hard to talk, to say things, to communicate beyond the necessary and about some inner feeling.

And as I did my research after our trip to Norway I began to learn about the German Occupation, the Quislings, collaboration and resistance. A darker, more complicated history than I had imagined.

For an excellent English-language introduction to Norwegian reassessments of the German Occupation, collaboration, adaptation, complicity and post-war justice see this blog entry by Sindre Bangstad.

See also the 2011 collection, Nordic Narratives of the Second World War, H. Stenius, M. Österberg, and J. Östling available here as a PDF and this thoughtful review by Norbert Götz. See particularly the chapter by Synne Corell, 'The Solidity ofa National Narrative: The German Occupation in Norwegian History Culture.'

I have some Scandinavian ancestry myself - my maternal grandmother was a Swedish American - Dagmar Lundholm - which, if you do this stuff, would make me a quarter Swedish. Not that you'd know.

(800,000 Norwegians left Norway

for the US and Canada between 1825 and 1925. That's about a third of the population and second only to Ireland in the percentage of the population to

emigrate to the USA). Many of the emigres were tenant farmers, husmenn, from the east of Norway.

I visited Sweden on a study trip years ago when I was looking at human-centred design principles in computer systems - a very Swedish approach to sorting out the world. And I'd

read the Wallander books and loved them and found them scary. That sense that something was changing, that a darkness was emerging, forces of disorder and criminality, that under the serene

surface not all was as it seemed. That the homogeneity and consensus were maybe not so binding as I'd thought and anyway the world was changing.

I read a piece by Karl Ove Knausgård on the 'inexplicable mind' of Anders Behring Breivik where he said that 'there is also something deeply sincere, almost innocent, about Norwegian culture;' that there is a strong patriotic feeling that people share on Constitution Day.

I was reminded of an old photo I had come across of a National Day procession in 1945 at the isolated settlement of Jøvik under the Lyngen Alps and a painting by British war artist, Stephen Bone, of Midsummer Midnight in Tromsø in 1945.

Knausgård seems to see Breivik as an inexplicable case who has little or nothing to do with the society he lived in. Although I have not read it, the book about Breievik by Åsne Seierstad - One of Us: The Story of Anders Breivik and the Massacre in Norway - appears to try and locate Brievik within Norwegian society (see this useful review by Ian Buruma).

For both authors, for the country itself, the massacre carried out with such cold calculation and glee by Breivik was 'Norway’s greatest trauma since the Nazi occupation' (see NYT review of One of Us). John Loyd, reviewing the book in the FT says, 'We get some, but not much, of the political context; less about the way in which Norway came — or did not come — to terms with the rapid immigration it underwent in the 2000s.'

Seierstad herself has said that Norway has learnt nothing from the Brievik massacre. But the report of her talk suggests that what she meant was that the police and anti-terrorist forces in Norway needed shaking up.

(The police response does seem to have been lamentable - see the Gjørv Report).

Maybe by this she means - as she said - that Norway would rather forget and pretend that it did not happen, and by implication that it could not happen again, than look at how Norway or parts of its public sector or political class or elites or media or who knows what might respond to the context that had some part to play in the creation of Breivik's 'inexplicable mind'.

The Gjørv Report, a report into the Brievik massacre of 22 July 2011 ordered by the Norwegian parliament and published in August 2012 was highly critical of the government and the police. In particular it concluded that it should never have been possible for Brievik to park his van carrying a 900kg fertiliser bomb next to government buildings in central Oslo that had been identified as a possible terrorist target in 2006. Even the parking ban in the street was poorly implemented and the physical barriers that had been agreed in 2010 had been delayed in their emplacement.

It went on to castigate the leadership of the police force on the day of the massacres for failures to communicate, to get a helicopter to the island of Utøya, to provide a boat that could carry special forces to the island, for not enlisting the help of volunteer boat owners.

The security forces were also criticised for failing to act on a Customs tip-off over the import of potential bomb making equipment from Poland and for not spotting Brievik's presence on the Internet. Norway's gun control laws were also criticised.

The report made 31 recommendations ranging from preparedness to police helicopters, the banning of semi-automatic guns, changes to privacy legislation and 'improvements in shift patterns for police officers, too many of whom were just working office hours'. As a result of the report Norway's police chief, Øystein Mæland, resigned on 16 August 2012.

The Norwegian Prime Minister, Jens Stoltenberg, apologised for the shortcomings revealed by the report in an address to the Norwegian parliament on August 28 2012. 'He also announced new measures to improve security, including providing police with military helicopters, boosting funds for the police and improving emergency exercises at all levels of "public administration." ' (BBC News). An English language version of some of the report is available here: Final report of the 22nd July Commission, Norway

I had one of those Norwegian wool sweaters with the black and white patterning - that could have been taken from a flecked piece of Lyngen Alps gabbro - and it seemed to sum up something for me about Norway, solid, simple (as in uncomplicated), sincere, practical. And everlasting. But what, really, did I know.

But I also came across the documentation of the Falstad Centre and the 4,000 people convicted of informing on their fellow Norwegians to the Nazis or the Norwegian Quisling police during the Second World War. It said that, 'the fear of informants had a devastating effect on society. Trust between people was destroyed, and insecurity and suspicion spread in society. The use of informers had consequences for social life in Norway even in the postwar era, and has made a deep impact on many people up until now.' ( Falstad Centre, The enemy within – Denunciation in Norway during WW2 p.18).

And then I began to read more recent Norwegian studies (that are in English) of the IIWW and reviews of these - like this blog entry by Sindre Bangstad, (2015) and Synne Corell (2011), 'The Solidity of a National Narrative: The German Occupation in Norwegian History Culture' in Nordic Narratives of the Second World War, H. Stenius, M. Österberg, and J. Östling available here as a PDF and this thoughtful review by Norbert Götz.

I met very few Norwegians. We were only there for a few days. People seemed pleasant but disinterested in me, or where I was from. Sitting in the big breakfast room at the swish hotel in

Tromsø Norwegians getting ready for the day's work seemed very matter of fact, earnest but not hugely so. I had a fear of offending someone. Saying something bad about Norway.

But what bad was there to possibly say? One of the bar staff did give us a free round of drinks which was really nice. But the place generally felt a bit tight lipped. As if it were not going to

take lessons from anyone. Even though none were being offered.

When I stopped in the shop in what felt like a place way out on a limb - the road to Jøvik - I had somehow expected the woman serving to be curious about

where I was from, what I was doing there, stumbling into the shop in late April weary from driving. She was perfectly friendly and seemed slightly taken aback when I asked if I could help myself

to some coffee - as if any fool would know that that is what the coffee was there for. And on a long road like that in New Zealand passing drivers would have lifted a laconic and matey finger to

acknowledge your presence, a shared if rather thin bond of location and place.

I recently got an email from someone who lives up near the locality of the II World War (and later, NATO) Lyngen Line defences created by the Germans during the Occupation. He'd

come across my website. He told me I had misidentified a mountain and suggested an alternative. No greeting. No goodbye. No comment. I made the change. (I deleted the photo in fact and

thanked him and told him I was hoping to come in September but nothing came back.)

But that is OK. I was a stranger with my own stuff going on, my own excitement at being there. My own petty researches and mis-identifications. Why should anyone care? I was

passing through with my own concerns. Getting to grips with studded tyres and a filler cap that wouldn't - thankfully - let me get the diesel pump into it. I didn't know what to expect. I

had done no research. I was an empty canvas waiting to see what Norway would paint me. Or rather, that I would paint of it.

Funnily enough, and just as I was about to leave this page feeling pretty dissatisfied with my efforts, I thought to myself, 'I'll just have a quick search through the online Financial Times to see what's been reported about Norway recently.' As you do. Being thorough and all.

I came across one of the FT's in-depth 'Analysis' articles titled, 'Norway: environmental hero or hypocrite?' And it appears that all is not well in paradise. First, it notes that last year Norwegian authorities gave the go ahead for millions of tonnes of industrial waste from the mining of titanium oxide (for tooth whitening of all things) to be pumped to the bottom the 300m-deep Forde fjord in central Norway. It also notes growing pressure to open up the world-renowned Lofoten Islands - the jewel in Norway's eco-tourist crown - to oil and gas prospecting.

It seems that behind Norway's 'moralising' (a Norwegian industrialist's word, not mine) on environmental matters abroad it is not practicing what it preaches. So, for example, on the day in 2014 that Norway’s parliament began discussing whether its sovereign wealth fund should pull out of coal investments a state-owned company opened an, albeit 'small', coal mine in the Norwegian territory of Arctic Svalbard. Perhaps more importantly, it has also emerged that while economies like the UK and Germany have cut Greenhouse Gas Emissions by about 25% since 1990 the emission of CO2 in Norway has increased by 23% in the same period. This is due both to more traffic emissions and more emissions from the growth of the oil and gas industry.

The leader of Norway’s leading environmental lobby group, The Future In Our Hands, Arild Hermstad, is quoted as saying,

“We are winning the championship on what we do environmentally abroad but in our own country it is like we are not even in the competition. When it comes to the difficult decisions and the people might be a bit angry, then we can’t do it.”