Mountains VIII: The Pitsilia Hills - Khirokitia to Kalo Chorio

I was very undecided on my itinerary for my second day in Cyprus in January 2013. The previous day had been the coldest off the year with significant snowfalls in the mountains. I would have loved to have gone up into the High Troodos but many roads were closed and car I was driving was completely unfit for snow.

I pottered around small roads and took a walk into the valley behind the Khirokitia Neolithic settlement (see here Khirokitia) enjoying the warm sunshine. But I was undecided what to do next. I thought of possibly going to Lefkara and the lace villages behind Skarinou. In the end I decided to traverse in a fairly haphazard fashion the southern Troodos foothills and to have a look at the Commandaria grape-growing area (of which more on next page).

By now the temperature was 10°C but I knew that it would get colder as I climbed the hills and I wondered where and when I might run into the

snow.

The first part of my route took me high above Khirokitia village though rich green fields of barley, carob and olive and past a massive new villa being built on the first marl rise above this delightful scene. Beyond this I passed through dramatic denuded marl hills where a fire had burnt everything in its path.

You do wonder if eventually the whole island of Cyprus will be covered in villas. The appetite for land and concrete seems insatiable even to the passing tourist. The economic crisis, the international bail-out and the coming austerity may put a dent in this hectic and, one feels, ultimately destructive dynamic.

I saw signs in billboards advertising new villa complexes in the more familiar Russian Cyrillic script (see my Russian Connection page for more) but also more rarely in Chinese script. Whether of not the Chinese will take up the offer is a moot point. I read in the FT recently that some anti-graft body reckons that $1Tn have been siphoned out of China by corrupt officials and presumably they will be looking for somewhere nice to park this very ill-gotten gain (see Lex FT 10.02.2013).

The sunshine was beautiful as it flitted behind a few drifting clouds. I stopped in a big lay-by that showed the old track of the road and took a photograph of the reservoir lying in the hills below me.

This was the Kalvassos Reservoir. I had driven up to it through the bone dry Vassilikos valley in June and taken some pictures of the gnarly rock formations near the Kalvassos copper mine. On the way back in the scorching heat I had stopped and tried to get a picture of a family of bee-eaters catching bees from a perch on a telephone wire. They were very wary and my only picture was a blur of bee-eaterly colour.

In conversation with someone I had been told that the winter rains in 2012/3 had been very good and that the reservoirs were all full. The picture above suggests this wasn't the case at Kalavassos in January 2013 (see my page for more on Cyprus' water issues).

You would think these beautiful (and to Brits exotic) birds would be treasured, (like the Hen Harrier in the UK which faces extinction due to the alleged attentions of grouse-moor keepers). But Bird Life Cyprus ran the following story in 2011,

The thorny issue of Bee-eaters and beekeeping was tackled at a June 20th Nicosia workshop, organised by BirdLife Cyprus with support from the National Agriculture Network.The issue has been on the agenda for years, but last autumn the Republic gave a derogation for the shooting of bee-eaters by bee-keepers. In practice, the derogation was never implemented but message got out that ‘hunting of bee-eaters was legal again’ and as a consequence many bee-eaters were shot during autumn 2010.

Bee-keepers also succumb to the lime-sticks and nets of bird trappers in Cyprus intent on making money from the pickled songbird trade.

I continued on my way climbing higher into the sparsely-peopled hills, past Lageia and through Ora, Melini and Eptagoneia.I stooped to take a picture of a stream and big alder trees which I had not noticed before in Cyprus and then pushed on for Arakapas, which nestles in a bowl and produces mandarins, before a long climb to Kalo Chorio.

The hills I travelled through did not seem to be full of vineyards and happy workers. They were pretty enough but somehow enervating, sapping of energy and will. They seemed to me scrubby and unproductive. Every now and then I came across huge poly-tunnels carved into their steep slopes with complicated ponds and irrigation systems. I don't know what they were producing but they had a vague air of menace, if you can say that of a polytunnel.

Arakapas was the exception with its long-history of mandarin-growing from the 19th century. Here there were intense orchards of the 'Arakamas' variety that has a particularly attractive bouquet and flavour. The area sits in a bit of a bowl slightly lower in the hills and faces fully south to maximise the benefit of the sun's heat. It also sits in the fractured zone of the Arakapas Fault and this has maybe given rise to soils of greater fertility than the surrounding basalt-based soils on the steep slopes of the Pitsilia Hills.

The villages all seemed dead but it was a cold day not long after the Christmas festivities. I think I saw one woman in Arakapas and a group of schoolkids getting out of minibuses in Kalo Choria.

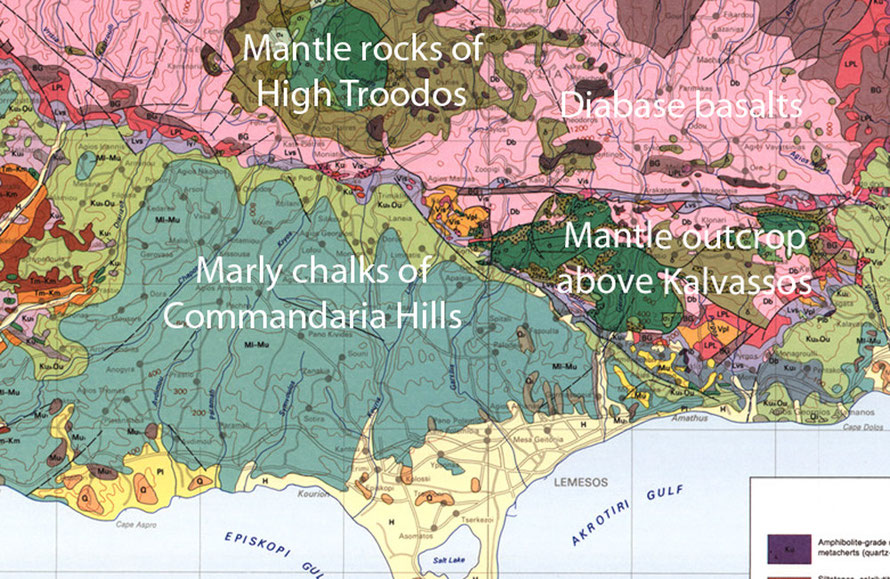

I later realised the importance of the underlying geology in this part of the Troodos Massif. The Pitsilia Hills are carved out of tough diabase basalts that resulted from the sea-floor spreading of molten magma 90 million years ago.

The resulting steep hills are thin-soiled and dry out quickly.

The route I was driving was pretty much over the top of the Arakapas Fault which lies east to west (see the purple line Between the Kalvassos mantle outcrop and the diabase basalts on map above.) Maybe this fault gave rise to the slightly chaotic feel of the hills and valleys in this part of the hills that seem to become more ordered and graceful further to the west.

Kalo Choria seemed a pretty dismal and disorienting place. I took a wrong turn at the fiendishly incomprehensible Pefkos Junction and ended up on a road to Zoopigi and the High Troodos.

I had seen very little traffic since the get-go back in Khirokitia but now I was completely on my own. I stopped a couple of times to try and work out on which road I was driving on my Cyprus Tourist Organisation sheet map but I was baffled.

I could see a flash new road beneath me but my road was increasingly littered with rock-fall debris. The temperature had fallen to 3°C and for the first time I began to encounter snow in the shaded turns and on the road. There were also large mud-washes in places and the whole thing began to seem a bit dodgy. As I turned a corner the snow-covered High Troodos and Mount Olympus (1952m) came into stunning view.

I was tempted to press on but the thought of the little Suzuki Splash starting to slide on a descent eventually turned me round back to Kalo Chorio. I still couldn't make head nor tail of the junction and indeed two days later descending from the foggy, wet, slushy High Troodos road from Kakopetria we made two full circuits of the junction without gaining any more sense of its arcane secrets.

As a result of this very poor signing, which is thankfully rare on Cyprus' excellent roads, I completely mislaid my turning and was soon bombing downhill on a main road sunk in a tightly turning deep valley that was taking me to Limassol.

I suddenly felt tired, hungry and pissed-off. I swore and cursed at the road, the signage, the Highways Department and the other road users who were all, naturally enough, oblivious to my distress.