Norway's Arctic Paradox: Tromsø and its marine hinterland

Introduction

It may seem obvious to the people who live there but I did wonder why a town like Tromsø (Romsa in Sami), with a growing population of 72,000 located 350km inside the Arctic Circle exists? And I did wonder why 6.8 per cent of Norway's population of 5.3m people live within the Arctic Circle. What do those 360,000 people do? Particularly in the winter?

For a dullard like me from the misty temperate climate of the UK the very idea of the Arctic Circle is one of extreme cold, ice, darkness and fleeting summers of mosquitoes and low-angled, dazzling sun. And there is an awful lot of Norway - it has a land area of 385,000 km² compared to the UK's 244,000 km². What is so appealing about living in the Arctic Circle?

Flying into Tromsø in low cloud and bumping down onto a runway surrounded by snow and ice in mid April just made the paradox more compelling. And the drive down to our waterfront hotel along roads running with meltwater in a constant drizzle did not give me any clues. Nor did the sullen mass of humped, snow covered mountains to the east. Nor the leaden waters of the Tromsøysundet - the Trømso Sound.

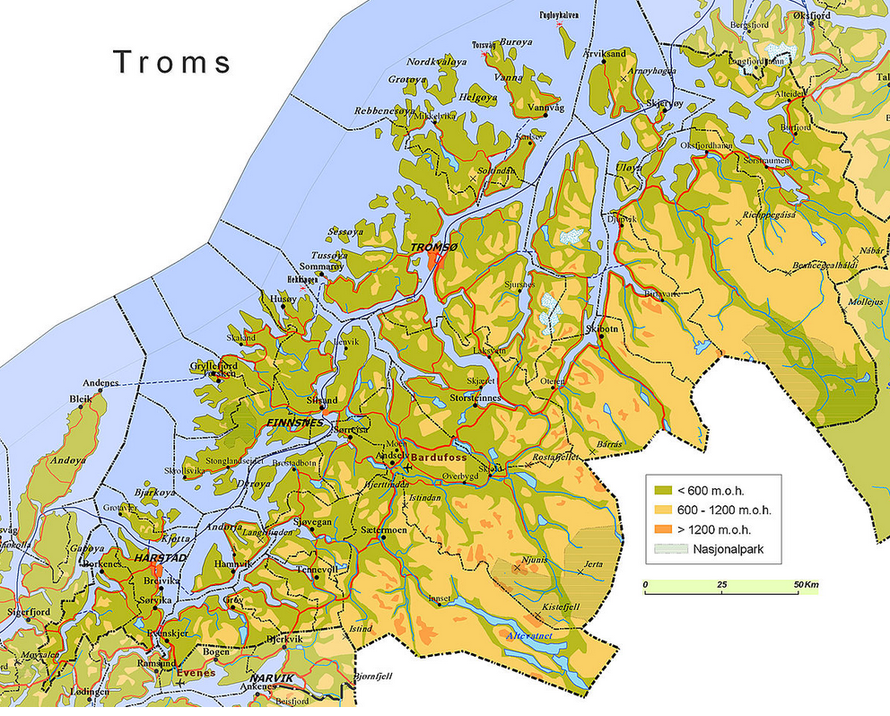

Take a look at a map of the Arctic Circle and you'll see what I mean.

The map above shows the Arctic Circle - that blue dashed line. And it shows the towns within it. Apart from a few places in Alaska (Prudhoe Bay and Barrow - populations 2,174 and 4,373 respectively), Greenland (Qaantaq and Nord) and the Canada's Queen Elizabeth Islands there is no population of any size north of Tromsø's postion at nearly 70° north. Yes, there is Murmansk just a tad to the south but that is Russia and Russia is a law unto itself when it comes to living in the cold and dark, no?

The map above usefully also charts the 10° C July isotherm (the point where the average July temperature is 10° C). This is sometimes used as a proxy for the definition of the Arctic Circle. And look what happens between the Labrador Sea between Canada and Greenland and Tromsø: the isotherm goes from way south of the Arctic Circle to 400km north of it. So hey, maybe it is not as cold up there as I thought it was.

And why is that? Because of our old friend, the Gulf Stream. This ocean current flows at a rate of between three and twelve million cubic metres per second into Norwegian waters after passing between Western Scotland and the Faeroe Islands and its effect is profound.

This huge trans-ocean central heating system, 'makes Norway the warmest climate on the planet for its latitude.' (see Ramberg, I.V., (ed.) (2008) The Making of a Land - The Geology of Norway p.486).

At a temperature of between 7-9° C the Gulf Stream transfers massive amounts of heat from the Atlantic tropics, via the Gulf of Mexico, to the Northern Atlantic. And by doing so keeps the coast of Norway and Iceland ice-free.

Were it not there chances are that Northern Norway would be covered with an ice-cap like that in Greenland. And the biggest town in Greenland is Nuuk with a population of 16,464. In fact, the total population of Greenland, which has a surface area of 2.166 million km² - that is five and a half times greater than Norway - is less than Tromsø's population of 58,000.

What persuaded people to settle and live so far north?

You can say that the warming influence of the Gulf Stream makes Tromsø a less brutal place to live than other areas on a similar latitude with much colder winters. But Narvik, 130km to the south, only has a population of 18,000.

There were 82,865 people employed in the country of Troms/Romsa in 2013 and employment grew by 3.9% between 2008 and 2013, slightly above the national average.

In part the answer must be that where there are land and resources to support life humans will be there. But why so many - 72,000 and counting - in Tromsø city and municipality and why so far north?

The riches of the arctic sea

The biggest clue to the size of Norway's population within the Arctic Circle does not lie on the land. Rather it lies in the seas to which Northern Norway has access to - the Norwegian Sea, the Barents Sea and the Greenland Sea.

It is the resources in these seas and connections and migrations to North Norwegian coastal waters that have made the survival and economic well-being of a relatively large population possible in Norway's three northernmost counties, Nordland, Troms and Finnmark.

Those resources in historical order go something like this

- fish (cod, capelin and herring)

- seal and whales

- and lastly oil.

GDP per capita in three counties of northern Norway - Nordland, Troms and Finnmark - was 65% of the Norwegian average in 2013. The figure for Troms was 88% whilst disposable household income was 98% of the national average.

Some history

Apparently the site of Tromsø in Tromsøya Island has been inhabited since the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago. In the Middle Ages Tromsø was the northernmost outpost of the Norse peoples and also inhabited by the Sámi people who lived in the broad cultural region known as Sápmi (Lapland) which covered large parts of northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia.

In the 890's the Norse chieftain Ohthere lived somewhere in the Troms district and claimed to be the northern-most Norwegian in Norway. Suggested localities for Ohthere's home include the islands of Senja, and Kvaløya or the fjord of Malangen.

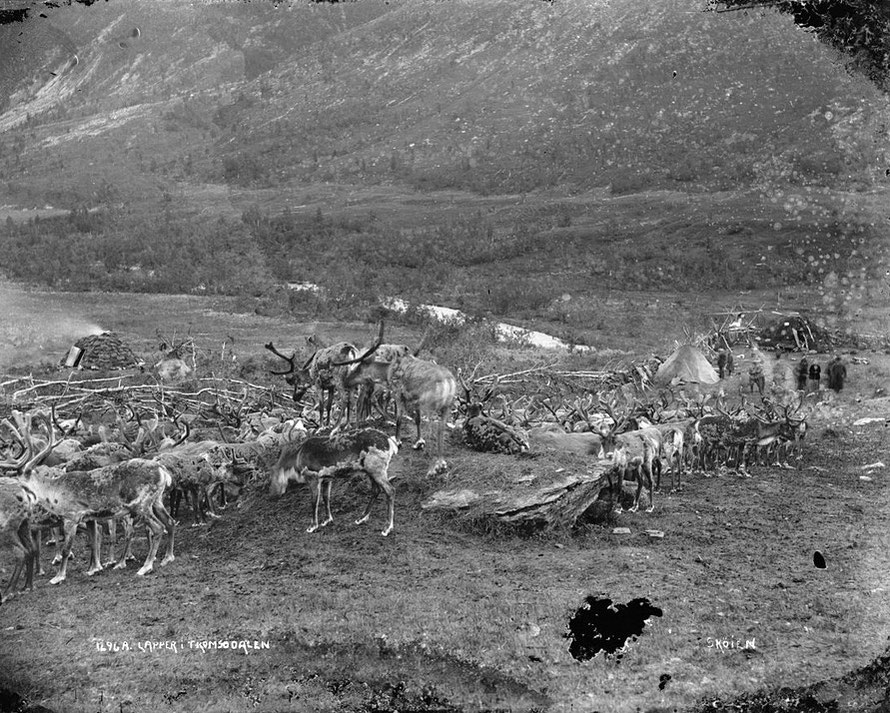

Ohthere was a chieftain and claimed, in a report to King Alfred made when he voyaged to Wessex, that his main wealth derived from his herd of 600 reindeer, taxes levied on the local Sámi people in the form of furs and hides from marten, bears, reindeer and otters and lengths of ship's rope made from whale or seal hides and walrus and whale hunting. Apparently he brought a Walrus tooth to King Alfred (see Ohthere Wipkipedia).

From his account to King Authur the seagoing prowess of the Northern Norwegians was well established. Ohthere travelled north and east to the Russian White Sea and south to Hedeby in Denmark.

An informal border appears to have existed in the Middle Ages between the land of Norwegians and Sámi (also called Finnas) to the south east of Tromsø. And at this time the Novgorod state had rights to tax the Sámi in the proximity of Tromsø although this border with Russia gradually shifted eastwards.

Although rich in fish resources the growth of Tromsø was probably held back by the monopoly exercised by Bergen in the trade of stockfis - dried cod (see my page on the fishing industry) . This was abolished in 1789 and Tromsø was granted city status (pop. 80) and grew quickly.

In the 1820s the 'Arctic Hunting boom' (largely sealing) began and by mid century Tromsø was the leading city in the Arctic Hunting trade (for comparison see my page on the importance of the seal trade in New Zealand as a force for early colonisation).

By the end of the 19th century Tromsø, sometimes called the 'Paris of the North', was an important Arctic trading centre. The association between Roald Amundsen and Tromsø was established as Amundsen led expeditions and his fatal rescue mission for fellow explorer Umberto Nobile from the city's port.

Tromsø was briefly the centre of the Norwegian Government in the Second World War before Norway fell to the German occupation and the government escaped to Britain. The town was relatively unscathed after the German invasion of the country but received thousands of refugees towards the war's end as the retreating German forces devastated the regions of Finnmark and North Troms in expectation of Red Army advances (which never came - see my page Operation Nordlicht).

The airport was opened in 1962 and the University, one of only four in Norway at the time, opened in 1972. In 1964 the urban area of Tromsø had a population of 12,602. By 2014 it had risen to 58,486 and become Norway's ninth most populous urban area (see Wikipedia: Tromsø).

Climate

Tromsø is said to have a sub-arctic climate having five winter months with a daily mean temperature below freezing (although the coldest months have average lows of -6.5 °C and the coldest low on record is only -21°C.

The sun remains below the horizon during the Polar Night from about 26 November to 15 January (7 weeks). And the Midnight Sun occurs from about 18 May to 26 July (9.7 weeks).

As we discovered in the last third of April twilight lasts for a long time and the sky is already light at 2am in the morning.

So why so many people in Arctic Norway?

To answer the question as to what has led to the relatively high settlement of Arctic Norway.

The answer seems to lie in the following factors alongside the milder than expected climate at such a northerly latitude.

- The Arctic Hunting boom (separate page)

- The Barents Sea and Lofoten Fishery (separate page)

- Port Services

- Higher Education

- Tourism

- Public Sector (Health, Local/Provincial Government, Transport Infrastructure)

- Oil and Natural gas.

- The Armed Forces

Employment is concentrated in the public sector (local government, health - a university teaching hospital - and other public services) and private services, the fishing/food processing industries, tourism and hospitality, and fishing and marine engineering related industries.

The Port

Tromsø port is ice-free, sheltered from the open sea, accessible from north and south, located on a deep fjord and strategically placed for the Barents Sea and Lofoten fishery, sub-arctic oil and gas, the defense of NATO's northern flank, and the exploration of the Arctic and the possible opening of trans-Arctic shipping lanes - a distant prospect.

Says World Port Source

Well within the Arctic Circle, the Port of Tromso is the major Arctic fishery in Norway. Its industries are mostly related to fishing, sealing, shipping, and the processing and storing of fish ... in the early 1800s, Arctic hunting began. By the mid-1800s, the Port of Tromso was a major hub for Arctic hunting, and it was trading with far-away places like Bordeaux in France to Arkhangelsk in Russia.

Says Tromsø Havn

The port of Tromsø is Norway’s largest fishing port and one of the largest cruise ports in the country. Tromsø is also the main logistics centre in the Arctic. In addition we have an ambition to be the preferred oil and gas port in the North Atlantic.

Port areas and wharves:

- Prostneset, located in the city center - cruise and coastal ferry activity

- Breivika, located due north of the city center - industrial and fishing related activity

- Grøtsund Offshore Base, located 12 km north of Tromsø at the entrance of the Tromsø Sound - under development. It will be [a] preferred base for handling and storage of goods and equipment to the oil and gas fields. Equally we will offer repair and maintenance facilities for oil rigs, vessels and underwater equipment.

Higher Education: University of Tromsø - The Arctic University of Norway

Tromsø University is one of Norway's eight universities and has 12,000 students, 10% of whom are international. The Tromsø campus has 2,567 employees and 9,307 students.

Founded in 1968, the UiT is young, but well established and belongs to one of the four mayor research universities in Norway. All four campuses in Tromsø and Finnmark are modern, technically advanced and well equipped. 25% of the academic staff is international. The advantage of an 8:1 student-teacher ratio guarantees close guidance and a beneficial learning environment. UiT Website

The University's location makes it a natural venue for the development of studies of the region's natural environment, culture, and society. The main focus of the University's activities is on the Auroral light research, Space science, Fishery science, Biotechnology, Linguistics, Multicultural societies, Saami culture, Telemedicine, epidemiology and a wide spectrum of Arctic research projects. The close vicinity of the Norwegian Polar Institute, the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research and the Polar Environmental Centre gives Tromsø added weight and importance as an international centre for Arctic research. Wikipedia

Oil and Natural Gas

Gas in the Snøhvit, Albatross and Askeladden fields 140km northwest of Hammerfest (pop. 10,000) was discovered in 1984 and was the first reserve to be developed in the Barents Sea, with considerable environmentalist opposition.

A large LNG plant has been constructed on the island of Melkøya for LNG exports. 'The LNG plant will emit 920 thousand tonnes of CO2 each year, an increase of Norway's total CO2 emissions by almost 2%.'

The Goliat oil field is located 85 kilometres northwest of Hammerfest and was discovered in 2000. Recoverable reserves are 174 million barrels. In April 2015 the 64,000 tonne, €5.3bn Goliat platform was about to be put in place to start production in 2016. The platform, designed to float in the Barents Sea, will be able to produce 100,000 barrels per day and store a million barrels of oil. It is behind schedule and over-budget due to 'engineering adjustments at the South Korean yard'.

Oil in commercial quantities has been discovered in the Johan Castberg field 200km north west of the North Cape and there has been some debate as to whether to develop land-based processing facilities in Northern Norway although Statoil is of the opinion that the find is not big enough to justify this.

Tromsø has seen some oil related work - in rig maintenance in 2011 which brought in 250 workers to local hotels. But from what I have seen it is not an oil boom-town.

Tourism

Tourism has become a major industry with 3.3 million overnight stays in 2014 in the three northernmost Norwegian counties. This is a 10 per cent increase on 2013 with many tourists coming by boat in cruise ships.

Arctic Norway has created two distinct seasons - the Northern Lights season and the Midnight Sun season.

There is also a thriving ski business and some other adventure sports seem to be catered for - see photo below.

Armed Forces

The Norwegian armed forces is a vital employer in Troms, having the seat of the 6th army division, Bardufoss Air Station, helicopter wings and radar stations in the county. There are hospitals in Tromsø (university hospital and main hospital for North Norway) and Harstad (from Wikipedia: Troms).

Satellite Ground Station Monitoring

There also seems to be an important satellite industry - providing ground station facilities for Polar orbiting satellites. Kongsberg Satellite Services had revenues of NOK of 482m in 2013 and employed 128 people.

A Competency Hub

Tromsø has a very strong competency profile, ranging from marine and maritime sector, preparedness, oil & gas exploration, health IT, space & satellites to biotechnology, medicine and social sciences.

The region hosts the world’s northernmost university, the Polar Environmental Centre, The Norwegian Institute of Food, Fisheries and Aquaculture Research, the Norwegian Centre for Telemedicine, and also high competence companies like Kongsberg Satellite Services, Front Exploration, NOFI Tromsø, Biotech Pharmacon, ProBio, Akvaplan Niva and Barlindhaug.

Tromsø is also committed to adding value to the local economy. Tromsø’s Science Park hosts the Barents BioCentre, a large facility for supporting the development of the biotechnology sector in the Tromsø region. The FRAM centre is another local hive of multidisciplinary research organisations that address the major challenges which arise from climate change in the North.

Solving the Tromsø paradox

All in all, then, there are a lot of factors that make Tromsø a successful Arctic paradox.

Firstly, the climate is not as daunting as the geographical position might suggest due to the warming influence of the Gulf Stream. This keeps the coast ice free and allows the city to make the most of its sheltered natural harbour.

Secondly, the resources of the sea in terms of the richness of the fishing grounds to the north and west and the more recent discovery of oil and gas have made it relatively easy for people to settle the coast from an early age.

Thirdly, Tromsø was lucky in that it escaped the damage and devastation that other cities and counties of Norway suffered during the Second World War.

Fourthly, what looks like the deliberate and planned economic promotion of Tromsø with the siting of a university and university hospital in the town and the transfer of other institutions to it has been important within the context of Norway's incredibly well resourced welfare state (in part financed by Norway's massive sovereign wealth fund) and presumably large infrastructure budget.